If Yan Sakai and Yan Bindiga self-help volunteer groups in Zamfara are left to roam freely and are not rehabilitated, they may adopt an ideology to justify their actions. They may become a bigger danger to the society than they presently constitute.

Saleh Momale points out that many non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and development partners are active in the North-East, a region which has witnessed an insurgency for 11 years now. However, Zamfara presents a deficit in terms of NGOs and development partners, whereas the humanitarian situation in Zamfara is equally as urgent or as dire as that of the North-East.

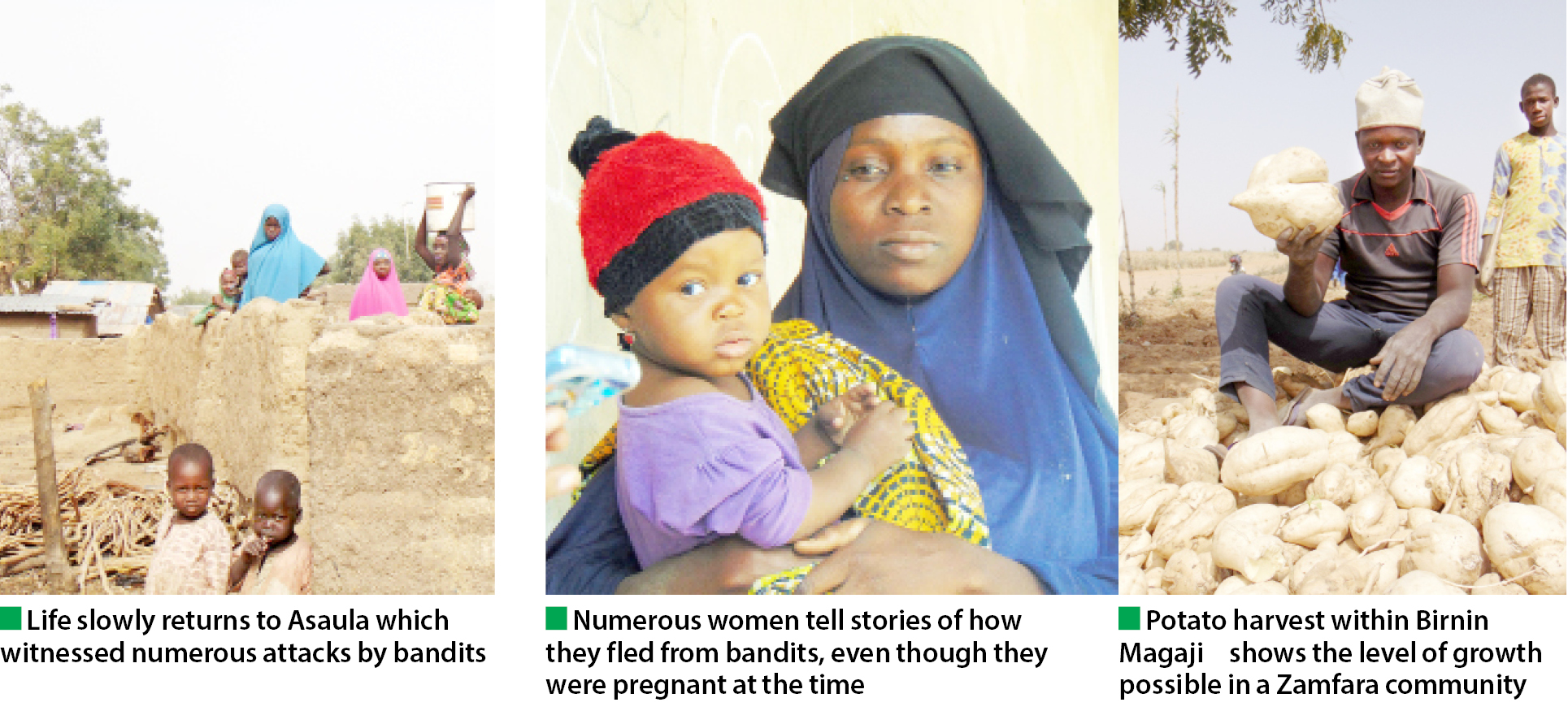

An encounter with broken and tearful men and women in remote pastoral and farming locations in the state last year confirmed that this is true. The local governments are not very functional, and so, the people at that level do not feel the presence of government very well.

“There may be a need to bring all the NGOs from the North-East back to Zamfara to start providing services at the local level. Zamfara is bleeding,’’ Momale, the acting executive secretary, the Pastoral Resolve (PARE) said. However, he acknowledged that government had made some effort to improve conditions at the local government level for the ordinary folk.

Zamfara is among the 10 states in the country with the highest indices of acute malnutrition among women, according to a recent report produced by the PARE and Search for Common Ground. The same report shows that 42 per cent of the population practises open defecation. It also highlights that 59 per cent of the “out of school” primary school age groups are girls.

The big question then is: What is the way forward for Zamfara, and how can this be achieved? “One key element still missing in Zamfara State is the strategic framework for sustainable management of rural insecurity. There must be a roadmap. If a roadmap is created, we will have a more peaceful, prosperous and highly enlightened community in Zamfara State.

We will see stronger local institutions with increased capacity to resolve emerging issues, and with increased capacity to work with security establishments in the maintenance of law and order,” Momale said, providing perspective on a matter that is very dear to him.

Rural insecurity

The PARE has done a lot of beneficial work among pastoral communities in Nigeria’s North-West. Momale explained, “We have been working with communities of pastoralists for over 20 years. In 2001, there was already a clear evidence of some of these challenges, particularly in Katsina State. And pastoral resolve had to move and start interacting with some of the stakeholders to resolve these issues.

Insecurity was highly pronounced in pastoral producing areas, and the escalation of insecurity in these areas will eventually affect the larger society in the long run. This is why we started working with institutions and security agencies to draw attention to the need to secure rural communities and manage or prevent the escalation of violent crimes.”

The PARE began work in Zamfara in 2016, monitoring some of the developments in the state, trying to document the level of displacements that were already taking place silently and drawing the attention of the relevant establishments of government, particularly at the state and federal levels.

It began sectoral or focused interventions when it received funding from the French Embassy through its project on strengthening civil society actions in critical areas.

Tension, suspicion

When the PARE commenced work in Birnin Magaji in 2017, it encountered a shocking level of hostility existing between two communities, in addition to a bewildering local situation. These were communities located close to each other that were not communicating because of fear, tension and suspicion.

Traditional authorities were very weak, such that they could not exert any influence over the activities of young persons who constituted themselves into informal vigilante groups, which in Zamfara and Katsina are popularly known as Yan Sakai, which means self-volunteers.

The Yan Sakai were already becoming very powerful and beyond the control of any local institution. The same applied to the Yan Bindiga, self volunteers located in pastoral communities.

Momale said, “Again, the political environment of the time tended to favour the activities of both the formal and informal vigilante groups, and there were strong allegations that some of these groups were aligned to the political leadership of the state at that time. The vigilante groups used to commit extra judicial killings of persons they suspected to be criminals. They could raid villages at their own will, without any intervention or deterrent from state institutions.”

This landscape was common in most parts of Zamfara.

‘Think of anything, it’s not there’

Fear and mistrust were some of the big challenges the PARE faced in the course of its work. Momale recalled, “There was mistrust of the security establishment, governments, civil authorities, and sadly, even traditional authorities. Local communities have lost confidence.”

The next major obstacle was the inadequate local government structure. “This was the weakness of local government administrations. In fact, the capacity of local government administration, particularly in Zamfara where we worked, and I think also in many other states of the North West, is very weak.

Communities are largely left on their own. There are barely few functional health centres, schools, extension services, veterinary services. Think of anything, it is just not there.

Government officials at the local government level mostly manage affairs within local government secretariats. They rarely go beyond to reach out to communities and constituents. The state government has been doing very good in terms of development of physical infrastructure, like roads, construction of schools, rehabilitation of hospitals, but the service provided by these facilities is something else.”

Island of possibilities

Birnin Magaji stands out as one community where the PARE had major impact, bringing peace, hope, integration and a major turnaround to the locality. It stands as a glowing island of possibilities in the crippling social and economic fog that has been cast over the area by bandit groups and ‘conflict entrepreneurs.’

Much training was extended to groups within the community. “Additional capacity for the local leaders, district heads and the Birnin Magaji Emirate contributed immensely in creating a stronger social order within the local government. When the crisis was escalating in the adjoining local governments, the division that was driving the violence in the other local governments was non-existent in Birnin Magaji. They suffered the consequences and faced the challenges as an entire community, not divided,” Momale added.

During my visit one sunny morning in March, I witnessed sweet potatoes being bagged outside Birnin Magaji. A potato was so huge that a farmer could not easily hold it in his palm. This highlighted the potentials most communities can offer if violence is arrested and a semblance of law and order sets in. Momale commented on the ground covered so far by the PARE: “It is really very difficult to say that PARE’s intervention on its own was responsible for some of the achievements recorded. We have to acknowledge the role of many stakeholders with whom we were working, and who acted positively. These include traditional rulers, community groups, as well as officials of the government.”

Rehabilitate vigilantes

Momale is optimistic that the security situation in Zamfara State will improve, five years down the line. His said, “If the reverse happens, we will see a comeback of the violence, a repeat of what is happening in Katsina; not only that, an escalation and probably a total breakdown of law and order.

I think what has been very helpful up till this moment is that all of these conflicts and violence taking place are not based on any ideology. The criminals’ only hope is to loot, steal and enjoy the wealth in their own way. That’s just their motive so far.

For the other elements like the aggrieved pastoral groups, their means of livelihood has been shattered, grain stores burnt, farmlands confiscated, and their cows have been rustled. They lack means of livelihood, so they are aggrieved and need rehabilitation. If that takes place and they are reintegrated, that would be excellent. If that does not happen, they will escalate and continue to live in that way.

Members of the Yan Sakai are largely uneducated and unemployed groups. If they are rehabilitated, provided with capacity, supported to engage in viable ventures, they would become more valuable and more useful citizens to both state and country.”

Groups may fuse

He gave a note of warning, “All the three groups may, in the long run, fuse, especially if an ideology is injected; either an ideology of insurgency, ideology of revolt against government, religious ideology, a cultural ideology, whatever sort of ideology, a socialist or capitalist ideology, any ideology that becomes entrenched in the mind of the people. They will likely end up with a revolt, which could take any form, depending on the type of ideology injected.”

Roadmap

Momale repeated his call for a long term strategic framework or roadmap for tackling rural insecurity in the North-West. This framework could be useful in states such as Katsina and Niger, which are experiencing various forms of bandit attacks or witnessing a Zamfara type of scenario.

He asked, “How are we going to deal with the Yan Sakai and Yan Bindiga? How are we going to deal with those groups, those communities? Those people whose farms, houses were destroyed. What will we do with extending education, with raising capacity development? What can we do to improve livestock production among the pastoralists? The vital question is: What is the strategic framework for dealing with all of these?”

Those who are keen on restoring peace to Zamfara have their work clearly cut out for them.

This piece was sponsored by The Pastoral Resolve (PARE).

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.