After 11 years of giving birth to three girls, Abuja-based, Fati had twins – a girl, Maryam, and the other “finally a son.” There was no getting over this elation.

Everything she wanted from her husband, Usman, she got. For him, it was only with the coming of his son, Usman Jr., that he had become a man and could boldly speak in public and at family gatherings.

The twins, now seven years old, with two younger siblings, have clear-cut chores. Maryam is being groomed to be a responsible girl helping her mother, cleaning up after her younger siblings, which includes giving an evening bath to two-year-old Mamza and changing his diapers.

While these actions have endeared Maryam to Mamza, something else that is also easily noticeable is how exhausted she is by the time she is done with the toddler, with little or no time to play or watch TV.

Although she is teased as the one who wakes up last because she enjoys her sleep and is also commended for being the most motherly sibling, there is the question whether her rights are being respected and her perception of a woman’s role and capabilities, distorted.

Section 12 sub-section 1 of Nigeria’s Child rights Act 2003 on Right to Leisure, Recreation and Cultural Activities, says, “Every child is entitled to rest and leisure and to engage in play, sports and recreational activities appropriate to this age.”

Usman Jr., on the other hand is not allowed into the kitchen, except it’s for a meal or to speak to somebody.

On why he doesn’t join the girls to do chores, “His father doesn’t want him to,” Fati responded with a smile and tone that showed she was in accordance with her husband.

A 2016 UNICEF report, ‘Harnessing the Power of Data for Girls’ said they spend more time on household labour than boys.

According to the 20-page report, girls spend 40% more time, or 160 million more hours a day, on cooking, cleaning, collecting firewood and caring for family members, than boys of the same age.

The report said, “Globally, girls aged 5–14 spend 550 million hours every day on household chores. A girl aged 5–9, spends an average of almost four hours per week on household chores. In some regions and countries, these numbers are twice as high.”

In the three countries – Somalia 64 per cent, Ethiopia 56 per cent and Rwanda 48 per cent – with the highest prevalence of involvement in household chores, on average, more than half of girls aged 5–14 spend at least 14 hours per week, or at least two hours per day, on household chores.

Worldwide, girls aged 5–9 spend 30 per cent more of their time helping around the house than boys of the same age, UNICEF said.

Adding that, “In some regions, the gender disparities can be even more severe. In the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia regions, girls aged 5–14 spend nearly twice as many hours per week on household chores as boys of the same age.

“In countries with available data on chores by type, almost two thirds of girls aged 5–14 (64 per cent) help with cooking or cleaning the house. The second most commonly performed task among girls this age is shopping for the household (50 per cent), followed by fetching water or firewood (46 per cent), washing clothes (45 per cent), caring for other children (43 per cent) and other household tasks (31 per cent).”

Just as the Sustainable Development Goal 5 on gender equality, recognizes and values time spent on unpaid household services, UNICEF, states that, the unequal distribution of household chores has negative impacts on girls’ and women’s lives.

The report said, the types of chores commonly undertaken by girls – preparing food, cleaning and caring for others – not only set the stage for unequal burdens later in life but can also limit girls’ outlook and potential while they are still young.

It said, “The gendered distribution of chores can socialize girls into thinking that such domestic duties are the only roles girls and women are suited for, curtailing their dreams and narrowing their ambitions.

“Household chores are usually not valued by the family and community the way income-earning activities are, rendering the contributions of girls less visible and less valuable, and having lasting effects on their self-esteem and sense of self-worth.”

Around the world, there are advocacies against such stereotyping.

In 2003, MTN, a communications company in Nigeria, produced a TV commercial, ‘Mama Na Boy.’ It was of a man calling his mother to announce the birth of his child. He tells her, “Mama na boy.” His very excited mothers began jubilating as the entire village joins her. It was soon hit with massive criticism for promoting male child preference in Nigeria and labelled a corporate rebellion. It stopped airing soon after.

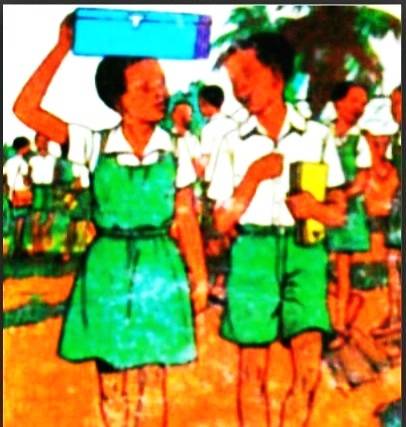

In Nigeria, the story of Mr. & Mrs. Salami’s family was famous for years as a primary school English set book. One of its most referenced pictures is of the young Salamis, Simbi and Ali. Simbi carries a metal-looking box on her head while Ali causally holds his book under his arm as the two chat on their way to school.

There has been a paradigm shift from this with school books in the country now presenting girls differently and in more positive light.

|

| Ali and Simbi |

Ugnada’s Dr. Moses Tetui, a health systems expert, in an article on taking steps to achieve gender parity in schools, said, school books still have images of a woman carrying babies and pots and men in suits holding a brief case.

Tetui, emphasised that getting it right from day one is crucial because, “The foundation we lay for our future generations determines the level of development that we can have as a society. Gender mainstreaming is one of the tools that we need to achieve this equality.”

In Britain, Medicines sans Frontiers’ Dr. Javid Abdelmoneim, created the documentary – ‘No more Boys and Girls: Can our kids go gender free?’ on BBC 2. The idea was to see if a radical experiment could change what kids think.

The documentary queries whether the way boys and girls are treated in childhood is responsible for society not achieving the equality between men and women in adult life. He also queries if stripping away subtle differences could be the way to raise kids with equal abilities?

A boy and girl, both about age five, featured in the 33 second trailer of the program, responded to the question, ‘Are men and women equal?’ The girl said, “Men are better being in charge.” The boy said, “Boys are cleverer than girls. They get into presidents easily. Don’t they?”

For parents to see the impact dress slogans have on children’s psyche and how it prepares them to be underpaid, girls were asked who do you think are better, boys or girls? All the girls except one said, boys are better.

Also, when girls were asked to describe themselves, Abelmoniem said they “only used words like pretty, lipstick and one of them used the word, ugly.”

Explaining to parents who took part in the survey the sequence and end result of slogans on four t-shirt samples, he said, “When you put your daughter in a dress that says “forever beautiful,” it ends up telling her that “looks are everything,” they end up thinking “boys are better” and that results in them being “made to be underpaid.”

One of the mothers said, “At first I didn’t really see the problem but as it progressed in the line of t-shirts and slogans, I could see the link between the first one and the others. It kind of makes some of the things that seem innocent, not that innocent after all.”

A consultant psychiatrist at the Federal Medical Centre Markurdi, Dr. Michael Amedu said, to correct the defects emanating from stereotyping, “the media is well poised in this regard. Our movies depict our cultural values and the way the girl child is depicted, is very often stereotyped. Also, when people hire domestic staff, you hardly see a boy child hired. It is girls, and some of them still don’t have the opportunity to improve themselves. There is need for public enlightenment down to the grassroots, and more awareness of the negative consequences of these cultural practices of stereotyping girls.

We also need studies done for comparisons among those who have passed through these hurdles and those who have not and look at the differences. In as much as we emphasise this, it is not to say that teaching children generally to do house chores is a bad thing. We need to be able to balance it such that the child does not grow up without basic self-sufficiency skills.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.