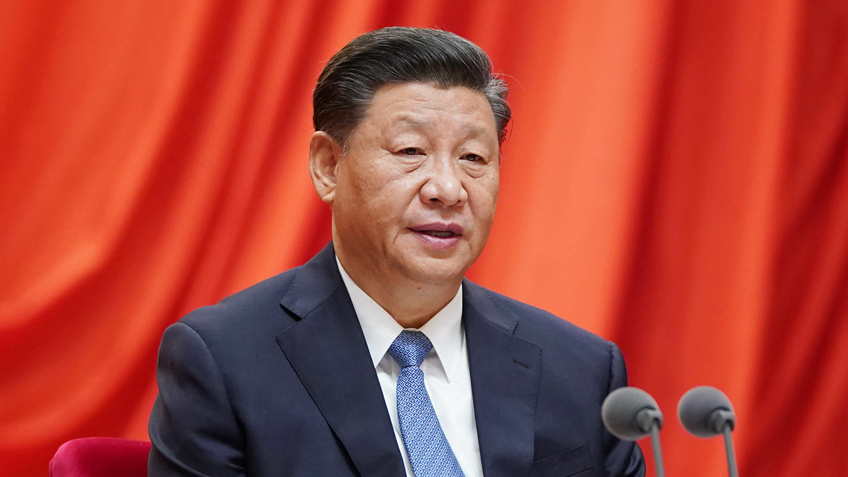

When Xi Jinping took power in 2012, some observers predicted he would be the most liberal Communist Party leader in China’s history, based on his low-key profile, family backstory and perhaps a degree of misguided hope.

Ten years later, those forecasts lie in tatters, proving only how little was understood of the man who is now China’s most powerful ruler since Mao Zedong after being handed a historic new five-year term on Sunday.

- Psychiatric nurses shift national election, name 5-man Caretaker C’ttee

- Tinubu donates N100m to Kano flood victims

Xi has shown himself to be ruthless in his ambition, intolerant of dissent, with a desire for control that has infiltrated almost every aspect of life in modern China.

He has gone from being primarily known as the husband of a celebrity singer to someone whose apparent charisma and aptitude for political storytelling have created a personality cult not seen since Mao’s day.

The colourful details of his early life have been rinsed and repackaged in official party lore, but the man himself – and what drives him – remain somewhat more of an enigma.

“I dispute the conventional view that Xi Jinping struggles for power for power’s sake,” Alfred L. Chan, author of a book on Xi’s life, told AFP.

“I would suggest that he strives for power as an instrument… to fulfil his vision.”

Another biographer, Adrian Geiges, told AFP that he did not think Xi was motivated by a desire for personal enrichment, despite international media investigations having revealed his family’s amassed wealth.

“That’s not his interest,” Geiges said.

“He really has a vision about China, he wants to see China as the most powerful country in the world.”

Central to that vision – what Xi calls the “Chinese Dream” or “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” – is the role of the Communist Party (CCP).

“Xi is a man of faith… for him, God is the Communist Party,” wrote Kerry Brown, author of “Xi: A Study in Power”.

“The greatest mistake the rest of the world makes about Xi is to not take this faith seriously.”

‘Traumatised’

Xi might not seem an obvious candidate to become a CCP diehard, though he grew up as a “princeling”, or member of the party elite.

His father Xi Zhongxun was a revolutionary hero turned vice premier, whose “strictness toward his family members was so serious that even those close to him believed it bordered on the inhuman”, according to the elder Xi’s biographer Joseph Torigian.

But when Xi Zhongxun was purged by Mao and targeted during the Cultural Revolution, “(Xi Jinping) and his family were traumatised”, said Chan.

His status vanished overnight, and the family was split up. One of his half-sisters is reported to have killed herself because of the persecution.

Xi has said he was ostracised by his classmates, an experience the political scientist, David Shambaugh, suggests contributed to a “sense of emotional and psychological detachment and his autonomy from a very young age”.

At just 15, Xi was ordered to the countryside in central China where he spent years hauling grain and sleeping in cave homes.

“The intensity of the labour shocked me,” he later said.

He also had to take part in “struggle sessions” in which he had to denounce his father.

“Even if you don’t understand, you are forced to understand,” he said, describing the sessions to a Washington Post reporter “with a trace of bitterness” in a 1992 interview.

“It makes you mature earlier.”

Biographer, Chan, said the experiences of his youth had given him “toughness”.

“He tends to go for broke. He tends to use a two-fisted approach when he approaches problems. But he also has a certain appreciation of the arbitrariness of power and that’s why he also emphasises law-based governance.”

Systematic, low profile

Nowadays, the cave Xi slept in is a domestic tourist draw, used to emphasise traits such as his concern for China’s poorest.

When AFP visited in 2016, one local painted a picture of an almost legendary figure, reading books between breaks in hard labour “so one could see he was no common man”.

That does not seem to have been obvious at the time though. Xi himself said he was not even rated “as high as the women” when he first arrived.

His application for CCP membership was rejected multiple times because of the family stigma, before it was finally accepted.

Beginning as a village party boss in 1974, Xi climbed to the governorship of coastal Fujian province in 1999, then party chief of Zhejiang province in 2002 and eventually Shanghai in 2007.

“He was working very systematically… to get experience by starting at a very low level, in a village, then in a prefecture… and so on,” said biographer Geiges.

“And he was very clever by keeping a low profile.”

Xi’s father was rehabilitated in the late 1970s following the death of Mao, massively boosting his son’s standing.

Following a divorce from his first wife, Xi married superstar soprano Peng Liyuan in 1987, at a time when she was much better known than him.

Even so, his potential was not apparent to all, exemplified by comments made by his host on a trip to the United States in 1985.

“No one in their right mind would ever think that that guy who stayed in my house would become the president,” Eleanor Dvorchak was quoted as saying years later in the New Yorker magazine.

Cai Xia, a former high-ranking CCP cadre who now lives in exile in the United States, believes Xi “suffers from an inferiority complex, knowing that he is poorly educated in comparison with other top CCP leaders”.

As a result, he is “thin-skinned, stubborn, and dictatorial”, she wrote in a recent article in Foreign Affairs.

‘Heir of the revolution’

But Xi has always regarded himself “as an heir of the revolution”, said Chan.

In 2007, he was appointed to the Politburo Standing Committee, the party’s highest decision-making body.

When he replaced Hu Jintao five years later, there was little in Xi’s past administrative record that foreshadowed his actions once installed as leader.

He has cracked down on civil society movements, independent media and academic freedoms, overseen alleged human rights abuses in the northwest Xinjiang region, and promoted a far more aggressive foreign policy than his predecessor.

In the absence of access to either Xi or any of his inner circle, scholars are left to survey his earlier writings and speeches for clues to his motivations.

“The absolute centrality of the party’s mission to make China a great country again is evident from Xi’s earliest recorded statements,” wrote Brown.

Xi has harnessed that narrative of an ascendant China to great effect, using nationalism as a tool for his own and the party’s legitimacy among the population.

But there is also evidence he fears that grasp on power might decline.

“The fall of the Soviet Union and of socialism in eastern Europe was a big shock,” said Geiges, adding Xi blames the collapse on its political opening up.

“So he decided that something like this shall not happen to China… that’s why he wants strong leadership of the Communist Party, with one strong leader.”

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.