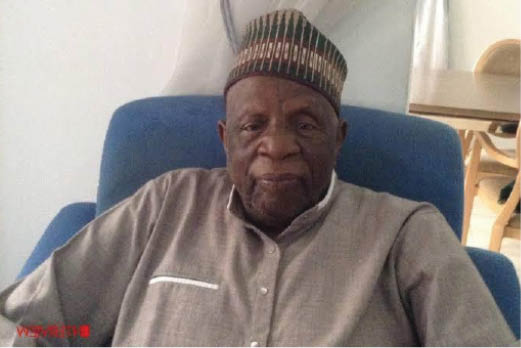

An elder statesman and former Managing Director and Chief Executive Officer (MD/CEO) of the Nigerian Industrial Development Bank (NIDB), Alhaji Abubakar Abdulkadir, died on Monday, July 15, 2024 at the age of 84. His funeral prayers took place at the National Mosque, Abuja after which he was interred at the Gudu Cemetery in Abuja according to Islamic rites. Weekend Trust in honour of the elder statesman, re-publishes this reminiscences interview we earlier had with him.

Can you recount your early days as a child growing up in Zaria?

I was born on June 13, 1940. I had my primary education in Zaria in an area called Angwan-Iya. From there, I moved on to what they called middle school and what is now called junior secondary school. From there, by the end of 1955, I moved to Barewa College (formerly Government College), where I spent five years. When I obtained the West African School Certificate (WASC), I joined the Barclays Bank (now called Unity Bank), where I spent two years.

In those days in northern Nigeria, if you did well in school they would trace you, particularly if you made Grade One or Two. They would try to find out if you applied for a scholarship or any higher education. Luckily, I was transferred to the Marina branch of Barclays Bank in Lagos. I received correspondence that the then minister of establishment noted that I had not applied for any scholarship. They said I should report to the newly opened Bayero College, Kano, which was part of the Ahmadu Bello University by January 15, 1961. From there, I took most of the A-levels, preparatory to a degree. I found out that I had English and History, but not Arabic, which was the core subject. So I decided to move to the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, where I read Economics (combined honours).

I graduated in 1967 and joined the then North Central State Government. We were the pioneers of the North Central State Ministry of Trade and Industry. There, I spent 12 years, rising from an industrial officer to chief industrial officer, then to acting permanent secretary of the ministry.

- What govt can do to tackle banditry, illegal mining

- Think the North will just be fine if Nigeria breaks? It’s time to think again

At that time, there was a coup and Murtala Mohammed took over. His first action was to nationalise banks. There was a campaign that those with good backgrounds should be taken to higher levels; and I was among them.

I moved to Lagos, where I was posted to the Bank of America, which later became Savannah Bank of Nigeria. From there, immediately Shagari came to power, and made me a managing director, Nigeria Industrial Development Bank. I stayed there for nine years. From there they deployed me back to the Cabinet Office, Lagos, directly in the Office of the Secretary to the Government of the Federation, as a permanent secretary.

A year later, the Ibrahim Babangida administration asked me to establish the Urban Development Bank of Nigeria, which I did in one and a half years. From there, I was moved back to the Presidency as permanent secretary in the SGF’s office. Then I moved to the Federal Ministry of Finance as permanent secretary. That was where I retired.

What were the unique highlights of your days in primary and secondary schools?

In those days, particularly in Zaria, not many people actually wanted to send their children to school. They would prefer to send them to almajiri schools (Islamic schools). My father, being a staff of the Nigerian Railway Corporation, decided that I should combine the two. So I finished the Islamic education by the age of 12; but before then, at the age of 7, I was sent to elementary school. I went to elementary school in the morning, and in the afternoon I went to the Islamic school. I could remember very well that in the whole of the class of 30 intakes, only two of us went there willingly. My grandmother took a letter from my father and we went on foot to the elementary school. The other child called Mustapha was the son of Alhaji Abubakar Imam. The class had 30 pupils, and 28 were brought in by some kind of coercion. They were coerced by the mai aungwa, village or ward heads, who went round and picked up any child they saw. In my own case, I went very early, so when we got there, the headmaster looked at me and said: ‘Mama, this boy is too small; why can’t you bring him back next year?” At that time if you were aged 6 to 7 you were considered very young.

I continued going to the school, and by the end of the year, there was an examination, and fortunately, the headmaster said I should be part of those who would write the exam. I came number 5 in the examination and he was so impressed that he said, “okay let us register him.’’ So I proceeded to Class 2.

That was one of the experiences I had. I discovered that I could really do this western education very well. From there, I went to the middle school in the late 1940s. After about a year, I fell ill (I had back pain). I went to the hospital and saw a doctor called Moore. He examined me and said I had TB of the spine, which was not correct! But he wrote it down and admitted me in the hospital. I was so frightened that I ran away and went home. My father was on leave, so he asked why I came and I said I would rather die at home than in the hospital. He asked what happened and I told him. He was angry with me. He tried to get me back to the school, but the school authorities, particularly the principal, Mallam Mora, said he would not admit me back until I was cleared by the doctor; something he was unwilling to do.

I stayed at home for 56 days, and at that time, they were about to take the examination into the Barewa College. My uncle told the then Emir of Zaria about my case and he requested to see me. He called the principal of the middle school and asked if he knew me. He said he did. He said I should be returned to school, but the principal said I had a disease that could affect other children. He said we should get another doctor to examine me. That was how I came back to the school. Dr. Barau Dikko, one of the first medical doctors in northern Nigeria, examined me and said there was nothing wrong with me. He said the only thing was that I had a calcium problem. He prescribed some drugs for me.

As a result of that, I lost one year before going to college. It was the following year that I took the examination, and fortunately for me, I was number one in the province for the college. Then I went to Barewa College.

Who would you say had the greatest influence on your life at that early stage?

First of all, it was my father. He really wanted the three of us: me, my immediate younger brother and the third one, Professor Idris Abdulkadir, who was the secretary-general of the National Universities Commission (NUC) to be educated. In the whole of Zaria, no one was going to western school. In fact, we were ridiculed, but my father insisted that we should go to school. His influence on us was tremendous.

Apart from my father, there was the then Emir of Zaria, Jaafar. When I ran away, he ensured that I went back to middle school. At that time again, there was no hope for further education, so I said they should buy me a sewing machine or get me married. The Emir just looked at me and said, ‘Young boy, you will go back to school and there will be a time when you will be buying so many sewing machines and giving to others.’ That prediction really had an influence on my life and it turned out to be true. The first thing I did after graduation was to buy a few sewing machines and give them to the sons of my friends.

What are the memories of Zaria as a historic town that readily comes to your mind?

There was a concentration of a number of schools in Zaria as a semi- urban town. What I can remember is the scenery.

Now, people are talking about herdsmen who are moving from Kano to Lagos. I can remember very well that there were cattle routes from Kano to Zaria, Lokoja and Lagos. There was no headache because they were routes that were created by the colonial government. So when people start talking about these herdsmen and farmers crises, I get bewildered because there was no conflict. I am sure you have been hearing about ‘Garki’ in so many towns? What that meant was that along the road there was a place where they would get water and have some rest before proceeding. That was what we called Garki. If that had been maintained, there wouldn’t have been herdsmen/farmers clashes. That is one of the things about Zaria that is vivid on my mind. I wish the cattle routes, which were created by the colonial people, were maintained so that we would avoid this problem.

Can you talk about your days in Barewa College?

Barewa College moved from Katsina. It was opened by Governor Clifford. It was moved to Kaduna, considered to be a more central location. When it was moved, there was the outbreak of the Second World War, so the children were asked to go home because they wanted to station soldiers there before transporting them to India. It was after the war that the school moved to Zaria. I met it in Zaria. I count my days at Barewa College as very happy days. The school was neatly kept and everything was done for you by the college. The only thing expected of you was to read and pass your examinations. It really accommodated a lot of students, starting from Tafawa Balewa, Ahmadu Bello, down to Shehu Shagari. My number was 1,162. It was really fashioned like Elton College. Nobody would tell you that you should obey; nobody would beat or abuse you, but immediately you entered the college, you would know the norms and the practice there and would automatically obey. Everybody was happy.

Later, Balarabe Musa thought it was too elitist, so he started admitting many students. Formerly, there were 12 provinces in northern Nigeria, and there was what we called common entrance examination for those who would be considered for various colleges. At the end of the exam, the first five in each province were taken. So a total of 60 students would be admitted into Barewa College. Primarily, they wanted to create teachers and high class civil servants, so they only took the best to the college. Altogether, it was a well-disciplined college. The quality of teachers was very high – something you cannot find nowadays.

Did you hold any position in the school?

No, I didn’t. There was what we called the school captain, and in each compound there was a head student. So they didn’t create many prefect positions in the school. It was Mr. Lanham who created what we called school captain. I was not a sportsman. The position I held mostly was in the Boys Scout Movement. I was very prominent in it and enjoyed it very much. I wanted to join the cadet corps, but I was not strong enough, so I settled for Boys Scout, and it was very successful.

What particularly attracted you to the Boys Scout?

Honestly, the way they behaved – helping others and going to camping – really interested me. The greatest experience I derived from it was the spirit of helping others.

How were your undergraduate days at the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria?

The ABU was an offshoot of the Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology. Again, life there was very comfortable. Students were treated like kings – very luxurious arrangement. Those with scholarships came with it, and the university even helped some students to get sponsorship from various companies. It was a very interesting time. We were about 1,000 students and we knew one another very well. It was really interesting.

Did you enjoy any scholarship?

I didn’t apply directly to the Northern Nigerian Government. As I told you, I was in the Backlays Bank in Zaria, and before then I was trying to get a job with the Northern Nigerian Government around 1961, but I didn’t. So I told the chairman of the Public Service Commission that I would not go back to Kaduna until I got my degree. So when I got admission into the ABU, the Dean of Economics asked if I had a scholarship and I said no. He said I should better go to Kaduna and get the forms. I said, “Sorry sir, I would not go to Kaduna because of a promise I made, that I would not go there until I got my degree.’’ He asked what we should do and I said he should know what to do, but I would not go to Kaduna. He said he had forms for me to fill. He sat me down in his office and I filled the forms. Amazingly, when they were giving the scholarship allowances I heard my name. That was how I got my own scholarship; I never expected anyone to do something like that.

Did you study Economics by choice or influence?

Back to my days at college, I listened to a lecture by a professor of Economics who came from Cambridge, and I became interested. At the end of the lecture, I went to him and asked if there was any way I could become an economist. He said certainly. He asked where I was and I responded that I was at Bayero College. He inquired about the subjects I was studying and I said: English, Literature, History and Arabic and he asked about my school certificate. When I told him that there was no Economics he said there was no way I could become an economist. I said, “But I like your subject.’’ He said he would go back to England and see what he could do about me. He took my name and address and went back to London. He consulted with his friends who suggested that if I could do a crash programme I could make it. He sent me a letter, telling me what to do. That was the beginning of my interest in Economics.

Apart from Economics, which other course would you have read?

I wanted to obtain a bachelor’s degree in Arabic. And because I couldn’t get Arabic, my mind shifted to Agriculture because I did not know the meaning of the word, ‘economics.’ I was preparing to get myself qualified fully because my school certificate was very good: Chemistry, Geography, Mathematics and all those subjects that qualify one to study Agriculture. So before that lecture from the professor I was preparing to read Agriculture.

You were also at the Small Scale Development Institute in India where you studied Small Scale Industry Development. What was the experience in India?

It was really a marvellous scheme created by one Mr. Chavez. An Indian and Ford Foundation helped him create the institute. The school was so successful that they decided to invite officers from various parts of the world. In the class where I participated, there were students from Sierra Leone, across to Japan. It was a real experience because there were a lot of interests in the development of small scale industries. That was where I got my postgraduate diploma. It was really an interesting experience.

You obtained your master’s degree in Economics at the University of Pittsburgh, USA, with a specialty in Industrial Financing and Banking. How did this influence your background in Economics?

First of all, I was already working at the state Ministry of Industry when one day, an American aide sent a letter to my governor, requesting for officers to go for further studies that would last between six months to two years. The governor gave them my name. They looked at my curriculum vitae and said I was already a graduate, so they could only put me for a master’s degree. They said they would take me to a university in America for what they called Development Economics. I chose Industrial Financing and Banking, then went there and spent two years at the University of Pittsburgh. It was in-service training because I already had a job. I got my degree at the end of two years. In the American system, to get a degree you must have at least 28 credits before being allowed to write your thesis. I got 36 credits, so the lecturer called me and said they only needed 28. He asked what we would do with the extra eight credits. I said I intended to do only a master’s degree. He said, “What about PhD?” And I said no, let me write my thesis and go back to Kaduna. So he said they would keep the eight credits till whenever I would have time for PhD. Now I have already retired and there is no need for me to go back to university. It was really an interesting time in America, and the quality was very high.

How did a series of courses and training abroad shape your career as an economist?

They opened my brain to see things from different perspectives. I also became more skillful in the work I was doing in Kaduna. It also paved the way for me to go to Lagos. When they saw that I had all these certificates I went to Lagos with 25 others and they distributed us to various banks. At that time, the Federal Government acquired shares in banks, including First Bank and Union Bank, so they wanted Nigerians to look after their shares. I was automatically included and it made me more mature and skillful. I became more broadminded on how to approach economic matters. Indeed, if I were to come back to life I wouldn’t choose any other subject.

Having worked under civilian and military governments, which of them would you say exercised the highest level of financial discipline?

In government there is what is called general orders and financial instructions, which were the guiding principles or laws of civil servants. The soldiers were very much in a hurry, but the civil servants wanted to work within the laws to guard public money. But the soldier had no time for that. That was the beginning of corruption in this country. If a civil servant helped a military governor for a project, whether it was viable or not, he would also use the same method to acquire for himself. I wish we kept that financial instructions and general orders intact and followed it strictly to avoid the kind of corruption we are seeing now. Ordinarily, military administrations are more corrupt than civilians because the latter is a little more conservative in trying to follow laws. I am not saying the military didn’t do much; they did a lot, but every project cost more.

You were a director-general and economic adviser in the Presidency during the administration of the late Sani Abacha. What was your experience?

Abacha was worried about the development of solid minerals and agriculture. The only ministry they had was that of agriculture, there was no Ministry of Solid Minerals. So when I rejoined the civil service as an adviser, I organised a seminar on these two issues and it was very successful. We brought a number of internal publications within the ministry in the office of the secretary to the government. It was on that basis that the Ministry of Solid Minerals was created while that of agriculture was expanded. What you have now is an offshoot of what we did under Abacha. It was a good experience. I am very proud to have been an instrument for the creation of the Ministry of Solid Minerals and the expansion of that of agriculture. These were the prominent jobs I did as an adviser to the government.

The Abacha regime has been considered as one of the most corrupt in the country, to the extent that today, we hear about ‘Abacha loot.’ Having worked with him as an economic adviser, do you think his regime was that corrupt?

Let me tell you clearly, Abacha did not want to be corrupt. What happened was that when he took over, he was not popular with the British, he was not popular with the Americans and most of Europe. Remember, Nigeria was a pariah state and there were sanctions. So he thought he should make a kind of reserve account in various parts of Europe and America so that in case the sanctions went through the way the Europeans and Americans were after him, he would use the money to run the government. It looked foolish, but that was his idea. He did not amass the wealth for himself. However, along the line, he overdid it. I am not saying he did not want to enrich himself, but the bulk of the money was being kept so that he could run the government despite Europe and America. He opened the accounts with the Central Bank and diverted all the money into various accounts in Europe and America. If you opened the budget of Nigeria at that time, you would find nothing about stolen money. It was a normal healthy budget. Any money that came from the Central Bank would have been budgeted for. He would keep it there to hedge himself against Europe and America. It may look foolish but that was what happened.

You were a member of the commission of inquiry into the financial management of Jema’a Local Government Area of Kaduna State in March 1979. What did you find out?

After the exercise it was clear that those who were running the local government misused the money a lot. It was just about to collapse, but by the end of the day, based on our report, the state government had to inject money to save the local government. It was really corruption on a large scale, and I wish such would not happen again.

As the chairman of the presidential committee on the controversial IMF loan in 1985, what role did you play?

There was a lot of misconception. When Babangida came to power, Nigeria was heavily in debt, and there was a balance of payment they wanted to correct. When Babangida set up my committee to sample the opinion of financial houses and other stakeholders, I went round the country and the answer was that there was no need to take the loan. What the country needed was an overhaul of its economic structure. One of the ills was that the Naira was being supported very strongly by money from the treasury that kept its value the way it was – N2, N.5 to the dollar. We realised that this should not have been the case at all. We decided to find the real strength of the Naira to know how much help it would need; not just helping it in such a way that at all cost it had to be N2.5 to the dollar. That was when we had the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP). I also played a role there. The Babangida regime disengaged the Naira and allowed it to find its own level. That was based on our recommendation. Suddenly, the Naira started falling up to N20 per dollar. Unfortunately, we continued pumping money into the economy, thereby bringing the Naira further down the system. The situation started escalating until today that we are having over N300 per dollar. I wish we exercised a lot of control because I remember saying we should not allow the Naira to fall beyond N5 to the dollar.

Unfortunately, the commercial banks would not allow the CBN governor to maintain this discipline. They continued to ask for more money, saying they were out-lending. But now, some kind of discipline is going on. The CBN is injecting dollars into the system so that the Naira would maintain stability. But you can only do this to a certain point to improve your productivity.

What is your assessment of the current state of the economy under Buhari?

When Buhari came to power, all the economic indicators were not in good shape. First of all, oil prices fell from $120 US per barrel to below $40 per barrel. There was a lot of misuse of money, particularly during the election time. So the country was really on the verge of collapse, to be honest. Everything was not doing well, so he had to employ economic discipline. Fortunately for him, oil prices started improving, and today, we are well over $60US per barrel. This is an opportunity for him to bring out those projects he wanted to do earlier on.

What have you been doing after retirement?

I am enjoying my retirement. What I do now is mostly writing and reading, as well as other things I wasn’t able to do during my active years of service. I write more of articles, but people are trying to persuade me to start writing one or two books on what has been happening in the Nigerian economy since 1960.

I have all the time at my disposal now to do that; and I am entitled to my rest.

You still look active, even in your retirement age; do you do some physical exercises?

Of course I always do so, particularly in Kaduna. Every afternoon I go to the Murtala Mohammed Square and do some exercise. I also do some cycling, just to keep active.

What is your favourite food?

I like pounded yam with egusi soup, and sometimes I take okra soup.

You indicated in your curriculum vitae that you have travelled to 73 countries. How did you do it?

I started when I was in the Ministry of Trade and Industry in Kaduna. I visited about 10 countries. I made most of the travels when I joined the NIDB because I opened credit lines with the Bank of Japan, European Bank and the World Bank and had to visit them most of the time. I also had to attend some seminars and conferences. I didn’t really like much of the journeys, but I found them very necessary in order to help my bank and the country in general.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.