In the North West region, the cradle of Hausa culture, history and civilization, we used to bow and tremble in the presence of powerful Hausa kings; Arab clerics who came here from across the Sahara; prestigious Fulani Caliphs who waved flags of the Jihad; wise Sultans and Emirs who succeeded the Caliphs; learned local Malams who we proclaimed as “successors of the prophets”; merchants such as Kundila who drove caravans of donkeys all the way to Gonja forest; and eminent politicians of great stature, Sardauna and his contemporaries. Today, instead, we bow and tremble in front of bandits, armed robbers, cattle rustlers, kidnappers, rapists and plain killers.

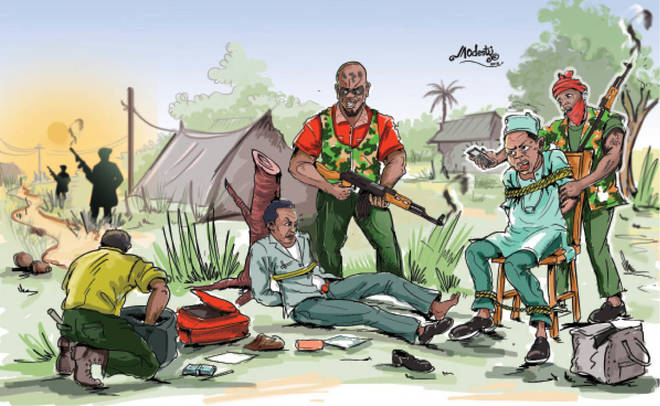

Normally there is a honeymoon period after elections but this year, there is grief, anger and deep frustration in the populous North West states so soon after the 2019 elections. Before the re-elected President and the six re-elected governors of the region had a chance to roll out their second term programs, the bandits moved in and successfully foisted an agenda on all of them. They have sacked entire towns and villages; killed untold numbers of people, wounded thousands more, rustled hundreds of cattle herds, stopped thousands from going to their farms, rendered large commercial farms unvisitable, rendered whole emirates destitute, made scores of rural and urban roads impassable, plucked an untold number of people from highways and villages and held them until ransom in millions of naira was paid, and they finally chocked off the Abuja-Kaduna highway, the lifeline of at least seven states to the Federal Capital.

When armed robbery first exploded in Nigeria soon after the Civil War ended in 1970, those of us growing up in the North mostly read about it in the newspapers. To us it was a distant spectacle. The military rulers quickly responded with the Robbery and Firearms Decree, under which hundreds of armed robbers convicted by Special Robbery and Firearms Tribunals were executed all over the country. The Bar Beach in Lagos, especially, was drenched in the blood of executed armed robbers while thousands of Lagosians flocked to watch.

Sometimes the military rulers tweaked the method for greater effectiveness. In 1984, under the Buhari military regime, the Military Governor of old Anambra State ordered that every condemned armed robber should be taken to his hometown and executed there, in order to bring shame to his hometown and put pressure on community elders. There was this story in The Guardian at the time, of a robber who identified a village near Nkpor Junction as his hometown. He was taken to the village in three military Land Rovers and was tied to the stake. As the executioners lined up, a score of village elders led by the traditional ruler placed themselves between the executioners and the condemned man and said he was not a native of that village. They asked him to point out his father’s house, which he could not do. The soldiers had to untie him, took him back to Enugu and executed him there.

For 25 years Nigerian armed robbery was relatively civil because armed robbers went for the money and largely spared the victims’ lives, unless one resisted or if the victims had no money. In the late 1990s, we suddenly had a new phenomenon in the North East and in Birnin Gwari where robbers opened fire at speeding vehicles, which crashed and they then robbed the dead and injured occupants. Some people said at the time that the new breed of robbers were ex-Chadian guerilla fighters. For forty years we grappled with the problem of armed robbery but then, a solution suddenly came in the name of technology. With the coming of GSM phones, armed robbers found it difficult to isolate a house and strike. Then came debit cards and ATM machines and most people no longer keep money in their homes. Technology nearly put armed robbers out of business. Unfortunately, it provided fertile ground for the rise of kidnapping.

From the accounts of several dozen victims, the template of Nigerian kidnapping is now well known. It usually begins when a vehicle travelling on the highway comes up to a makeshift checkpoint mounted by men in military or police uniform. Most kidnap victims at first think they were stopped by soldiers. When Malam Bello Zaki was stopped by uniformed men near Kazaure, he referred to them as “officers” and one of them brusquely said, “Kai, we are thieves!” Victims are then marched into the bush for hours on foot, sometimes on motorbikes, until they arrive at an open-air camp deep in the bush. Family members are initially held in suspense in order to create pressure, and then the tortuous negotiation for ransom begins, often with a demand for impossible amounts.

This is where technology comes in. Central to the kidnap for ransom operation is the GSM phone. Without it, kidnappers will be unable to contact family members and arrange ransom payments. At best they must limit kidnap operations locally to persons they know. Detecting kidnappers on the ground is difficult because they use their comparative advantage, which is thorough knowledge of the bush. Since GSM is the Achilles’ heel of a kidnap for ransom operation and since the entire GSM network, down to the masts and SIM cards is in the control of state agencies, how is it that kidnappers are able to get away with it so often that more and more folks are joining in the action and it is now Northern Nigeria’s only booming industry?

It appears that kidnappers have a lot of technical advice about how to beat police detection. Those who do the negotiation for and collection of ransom are often far away from the kidnap scene, but they still communicate through GSM. It is not impossible to develop a software that can pick up all their coordinated communication and identify their locations with pinpoint accuracy. But having pinpointed it, striking at them and rescuing the victims without harm is another major challenge. In the heydays of Palestinian plane hijacks in the 1970s, the German GSG-9 commandos had those skills and I urge Police Inspector Adamu Abubakar to send some men to Cologne for training.

Even now, it is noticeable that the IG’s Intelligence Response Team led by DCP Abba Kyari is able to crack almost all kidnap cases involving high profile victims. However, hundreds if not thousands of cases involving not-high-profile victims go uncracked. The question everyone is asking is, what stops the IG from forming, training and equipping more teams such as Abba Kyari’s? Probably the quickest way to end kidnapping is to be able to apprehend most perpetrators and convince the others that it no longer pays. Can we, for example, have two Intelligence Response Teams per state?

Then there is the most puzzling element of the Northern kidnap pandemic, the Fulani angle. The first time a friend told me, ten years ago, that the armed men who robbed him in a commercial vehicle near Jebba were ethnic Fulani, I found it hard to believe, except that a Hausa man knows the Fulfulde accent very well. Now there is no doubt about it; most kidnap victims say the kidnappers were young Fulani men. The pastoral society is falling apart before our eyes and the elders are losing control over their kids. I saw an interesting post at the weekend in which Fulani Ardos reportedly told the Governor of Kaduna State that they lost control over their youths because they no longer have large cattle herds which the youths were patiently waiting to inherit. If indeed that is the root cause of this problem, I urge the Federal and seven North Western state governments to import three million cattle heads from Burkina Faso, Mali and Chad and give them free of charge to the Ardos. That is cheaper than buying drones and helicopters.

That is, if it not too late already. A man who knows he can earn ten million naira in one swift kidnap operation may no longer be patient enough to wait for his father to die before he inherits a herd of cattle.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.