Readers would have noticed that the title of this column was changed exactly two weeks ago from Politics and Economy to On the Contrary. It was purposefully and carefully considered to ensure I keep you updated with our contemporary Nigeria. When I officially started as a columnist one year ago, we decided to go with the initial title based on the scope of the column. I always look forward to your comments and discussions. I cherish every response that comes from every one of you.

As many of you know me now, as an academic, I try to limit this column to public sector governance mixed with a bit of politics. But that’s not all. The column will also touch on our traditional institutions, economic justice and socioeconomic challenges in the country. Of course, as some of you suggested, I would have liked to write on issues like military strategy, transport logistics and the health sector, but I do not have vast exposure to these disciplines. Nonetheless, I will continue highlighting the little morality stories that most people think are the problems in Nigeria—injustices, high cost of living and greed.

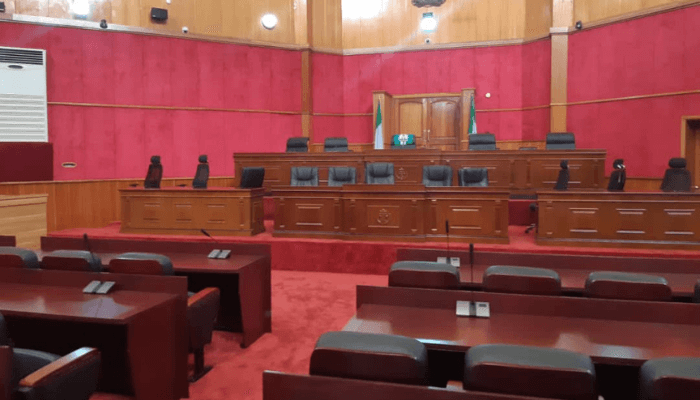

A sneak peek of what we will be discussing is reforms and a reflection of recent events like the recent PEPT judgement. Many Nigerians were disappointed with the outcome of the Supreme Court’s judgement, and it is within their right to be so. Atiku interpreted the judgement as legalising forgery, illegality, identity theft and perjury. And it is difficult for anyone from an objective position not to consider it. Similarly, retired Justice Muhammad had spoken on rot within the system and called for reforms. Before him, Senator Bulkachuwa narrated how his wife was involved in corruption as the President of the Court of Appeal.

These are worrying issues for the country because every country relies on its judicial system to succeed economically. Let’s not forget how everyone was elated by the judgment against the P&ID case in the UK court. I bet many of us wish courts in Nigeria operated like in the advanced economies. It can happen. It is not too late, but the intention has to be right. But we must be clear about the right solutions to our problems. I say this because we have situations where monetary policy solutions are applied to solve corporate governance and logistics problems. I will talk about that someday.

FG, Chinese consortiums sign N365bn contract to upgrade distribution lines

FG targets N750 to dollar by December

I must also emphasise that most of my perspectives are that of a traditional economist, not a street-corner philosopher. Socrates was also called a street-corner philosopher, so it is a limitation of mine. The point here is that please do not expect anything to change from what you have read before—the objectives and roles of a policymaker. I will not compromise to sing praises or whitewash any government policy when it goes wrong. Likewise, I will not be reluctant to applaud the policies done right because we want to see a working system in the country.

A good example is the current discussion of electricity supply by this administration. I worry that a government cannot differentiate itself from the private sector. When speaking on the efficiency of the electricity supply, Tinubu’s message was that what customers pay for a unit of electricity is far from being cost-reflective, especially in light of the recent devaluation of the naira. I expected this government to understand the difference between operating in the private and public sectors. Some may have missed this point, but thinking like this led us to the ongoing foreign exchange crisis and the fuel subsidy removal crisis.

The ideal role of the government is to act as a moderator—between the electricity suppliers and the consumers— instead of siding with the suppliers. They are expected to establish rules that protect consumers without stifling economic innovation and growth. They can design policies that benefit all—enhancing supplier efficiency and improving consumer equity. However, this requires a keen understanding of the limitations of public intervention.

Unlike private enterprises, which are motivated by profit, public institutions are mandated to deliver social welfare and public goods. Any attempt to uncritically apply private sector management ideas to public entities is likely to yield undesirable outcomes, as evidenced around the globe. The point is that the government must shift its thinking and responsibilities beyond what it will get to supplying affordable goods to consumers as against backing the producers to make a profit.

Governments need tax revenue, and private markets are vital for economic growth and job creation. On the contrary, consumers are the voters that brought them to power, and their welfare is a direct concern for any elected government. The government must understand that giving more power to businesses will lead to adverse outcomes, which harms consumers—the voters.

Circling back, today’s article is intended to acknowledge you, the reader—the voter. I understand that we all desire a Nigeria that works and protects the interests of the electorate. Overlooking this will go against the principles of public sector governance—a subject this column, and indeed Nigeria, cannot afford to neglect.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.