It began as a domestic dispute in a sleepy Fulani settlement of Bokki, Jigawa state but it ended in the brutal killing of a woman.

When Shuaibu Haro,30, and his wife Sahura, 20, fought, the woman left to return to her parent’s home.

Haro waylaid her in the middle of a footpath that intersects a nearby farm, and 500m from neighbours. He had a hoe. It was 11pm. He attacked her with a hoe, inflicted deep cuts. She bled out till death.

No one heard a thing till her body was discovered the next morning. He fled. His other family at home also fled when police named him suspect.

It is the latest news of a husband killing his wife (uxoricide) has rocked both Jigawa and the entire country. But wives killing husbands (maritricide) have also shared headline space. And more of both cases are coming out in the media-from Zamfara to Abia.

“I’m not really seeing it as a new trend; it has been there before,” says Samuel Oruruo of Africanquarters. “The only thing is it is becoming more pronounced because of fatality involved.”

Oruruo worked as a gender specialist with Voices for Change to product the “Being a Man in Nigeria” report into the difficulties of gender and masculinity in modern Nigeria.

The research considers pressure in the home and at work on men and highlights a need for couples to work together in their finances to reduce undue pressure on men.

It also considers gender inequalities that thrust women into positions of vulnerability and potential abuse even in the home.

And the reasons for resulting violence range widely: a woman wanting to retaliate violence, lack of trust, a marriage that is forced or early, refusal to have sex, financial breakdown, drug abuse, frustration at work.

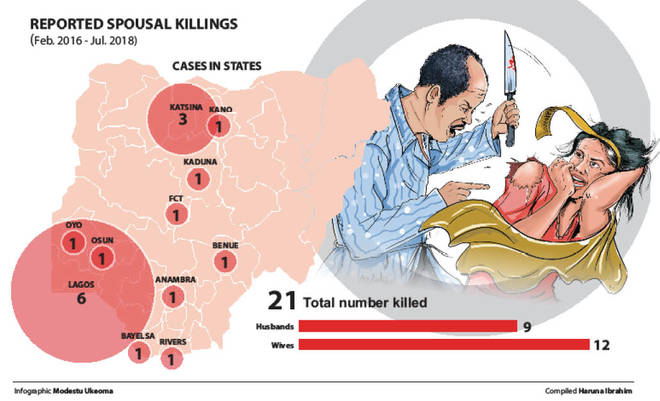

Daily Trust tracked 21 reports of headline-grabbing spousal killings from February 2016 until June 2018. Eight husbands and 12 wives were killed by their spouses. The reasons cited range from mundane (infidelity, inheritance, a misunderstanding, second wife, flirting) to outright bizarre. Among the bizarre: “refusal to wash clothes or cook food”, “argument over N200 soup money”, “refusal to cook Christmas food”, “husband had an accident, lost his teeth and started limping”.

They are all reasons social workers see, says Adakranda Harmis Chama, who coordinates work in gender-based violence for Plan International Nigeria in Maiduguri.

“There should be a lot of sensitisation and awareness in society,” says Chama.

“When these [killings] happen, the children are directly the primary victims of these killings. They are at risk of so many things. The support they usually get is no longer there.”

It begins with violence. Some 11 in every 100 women, married now or previously, have been subject of physical or sexual violence by a husband or partner, the National Demographic Health Survey indicates.

Spousal violence can begin at any time before marriage up until 10 years into marriage-for 13 in 100 couples. Women are behind in the battle of the sexes, but they are catching up. At least two in 100 women have inflicted some form of violence on their spouse at one time or other.

This July, Zamfara housewife Salamatu Shehu may have gotten encouraged when her husband indicated intention to marry a second wife. He’d planned on divorcing her because he couldn’t anymore bear her harsh attitude, sources said.

In the heat of an argument, she grabbed a stool and struck her husband over the head. He fell, unconscious and died shortly afterwards, police said.

Infidelity shouldn’t be grounds for death, advocates say.

“Talking to one another goes a long way,” says Oruruo. “The way you picture these things in your head is not the way they are. One can report an incident, but when you start talking to the person involved, it might not really be what you thought actually happened.”

That works for violence, but not death. And the foundation is laid long before the marriage.

In 2014, a 14-year-old teenager forced into marriage to a man 21 years he her senior made headlines when she fed her husband and three others food laced with rat poison.

Teenage brides forced into marriage and striking back is a phenomenon social workers are seeing more of in northern communities.

Early and forced marriages are a raging concern but advocates have been campaigning for informed consent.

“Parents have right to give out their daughters in marriage, but they must use that as a shield, not a sword,” says Chama.

“There should be informed consent, she should know what she’s going into, she should be of sound mind. And that goes for the boy too.”

Individuals suffering violence in marriage-whether forced, arranged or love-find it difficult to open up.

“Many see it as shameful if they reveal abuse. Many die in shame and anguish, and nobody knows,” says Chama.

The thrust is for strengthening marriage or family institutions with good counselling, adds Chama. The counsellors should be able to tell couples before they marry, that marriage will be “of good times and bad times”.

Counselling before and in marriage is a widely known idea; would-be couples from Sokoto to Osogbo go through it with parents or other elders right before they marry.

But professionals to actually dish the counselling are few and far between. Churches in Sokoto Catholic diocese have institutionalised it, covering everything from sex to finance and legal status and differences of between male and female.

“Fundamentally they are equal, created by God but social conditions and factors impose on them responsibilities that vary toward their home,” says Rev Lawrence Emehel, who heads a parish in Sokoto.

Counselling also gives would-be couples an idea how they may even share responsibilities, he says. But there is the old twist of horses drinking from a river.

“The challenge is with the couple themselves. When you are preparing them for marriage, they are busy preparing for wedding,” says Emehel.

“They spend plenty of time and mind-racking amount of money trying to mobilise resources for the wedding. We’ve always wedding is just for a day but marriage is for life.”

Couples routinely fall into bad times. Experts say some listening ear and a little communication might have helped the couples that have exploded into headlines for reasons of murder or homicide.

In Kazura village in Birniwa council area of Jigawa, housewife Hadiza Adamu’s family reported her missing for 20 days. Then residents discovered a headgear belonging to her near the mouth of a well no one used longer. Police would later find her corpse in the well.

Her husband did not report her missing and has been arrested as prime suspect. Police will determine his culpability.

But Sahura’s death is still a blip on police investigation radar. It is a crime to be investigated, and then dropped cold. It is also a death to mourn, and a marriage gone sour.

Tracking data compiled by Haruna Ibrahim.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.