Years ago, when I had my first son, a Nigerian family with young children came to visit. I met the woman, let’s call her Oby, at the university where I was studying for a master’s degree.Although our meetings were short and limited, we became somewhat good friends. I liked her and enjoyed our chats. She had always seemed like a reasonable person; was nostalgic for and frustrated with Nigeria in the same way that I was, and laughed over the same things I found odd in this country we were in. However, I had never met her family – not her husband – also Nigerian, and not her children. When she called to say she was coming to visit the newborn with all of them, they wanted to see this sister of mine I’m always talking about, I was happy. I had not seen her in months.

My mother who had come for omugwo was around too, and while she enjoyed the company of her Belgian in-laws, she often yearned for “people from home,” not just for herself, but for me as well. She often felt sorry for me, imagining me marooned in Belgium, starting life with a man I loved but to whom it had to be explained that it was considered rude in our culture to take or give things with one’s left hand. There was something about me as a child that made me seem fragile, brittle; something that could shatter. It wasn’t anything physical – I was not skinny until I had a bad attack of malaria the year before I entered university, but it was also not something I cultivated (I wouldn’t have known how). It made people want to protect me. I remember that a PE teacher in secondary school told me I couldn’t join the march past because she was worried I’d faint; a schoolmate at boarding school offered to help me with my laundry; and my mother worried about me not just going so far away but moving to a country where I had no family but the new one I was making. If you were moving to London or America, it would have been easier, my mom said. I had family – older siblings, uncles, aunts, friends, cousins- scattered all over the UK and the US, a ready support network. In Belgium, I had to create a completely new network, excited every time I could extend that network with one new person. Oby was one of the Nigerian women I had met and she was the only one my mother had not yet met. Where is she from? My mother asked. I didn’t know, just knew she was Igbo. What’s her last name? I didn’t know neither. When you see her, you can ask her, I said.

- NIGERIA DAILY: Mambila: 100 Billion Naira Down the Drain

- Parallel congresses: Pressure on Buni to sanction Shekarau, Amosun, Aregbesola, others

As if my saying it conjured her, Oby rang the doorbell. My husband, J, let her in. The bell woke up the baby who started to cry but the racket from Oby’s children – all three of them- was louder than anything my baby could have produced. They poured into my house, scattered into different parts of my small living room, touching things they had no business touching, asking what’s this? who’s this? Why’s the baby crying? My mother clapped her hands and said, children, say good afternoon to grandma. One of them, the oldest who was maybe six or seven, responded as he picked up a pen I’d been using to write earlier that day. Why’s this here? Iwant to colour. I took the pen from him. His siblings were playing some game under the table. Oby and her husband were completely unconcerned. They said what a beautiful baby I had, what lovely furniture, what delicious cake they’d been served. The afternoon stretched, and it fell to my mother, myself and J to keep their children in check, to stop them from poking a finger into my new baby’s nose, into his mouth, while every now and then, Oby or her husband would sigh and say between mouthfuls of cake, “They are European children; that’s how they behave. Wait until your son grows up. Ah! Your TV? He’ll break it! European children don’t sit in one place!” How and why is it normal for a kid to break a TV sef?

I could not understand their lack of embarrassment that someone else had to tell their children to settle down, that was when my mother countered and said , “Eh? European children?” They did not notice the sarcasm, that when J or I spoke a bit harshly to their child to don’t touch that! They did not take the hint.

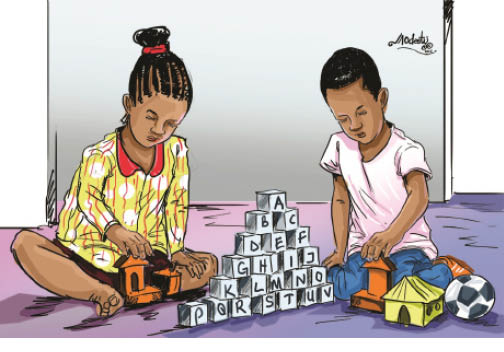

I didn’t see them again after that day. Oby and I maybe spoke a few times on the phone but even that dwindled to nothing. That visit shifted something in our friendship, so maybe she and her husband were embarrassed after all. Or maybe they were angry that we dared scold their children. I remembered her a few weeks ago when a friend complained that she had guests – recent transplants from Nigeria- whose children went straight to her fridge to look for “something.” I wonder what the effects of such dysfunctionality, raising kids and being a kid in a home without boundaries, are. I think of Oby’s children – no longer children now- particularly. I wonder how they’ve grown, what they’ve grown into. I wonder if Oby and her husband are reaping what they sowed, and if they are heaping the whole problem on Europe.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.