As of this writing, events in Zimbabwe were still hazy. The army had yet to inform the world of their real intentions in putting President Robert Gabriel Mugabe under lock and key in his official residence. But when a president’s presidential palace is turned into his prison he needs no one to tell him that the Nigerian lorry driver who painted “no condition is permanent” on his lorry was truly wise.

Despite the paucity of information on what is happening in that country, it is still possible to draw some reasonable conclusions from the action of the military top brass. Whatever political settlement might be reached by the leading actors in this shock drama, it is fair to draw the conclusion that the sun has suddenly set for the world’s oldest president. At 93, everyone else held the candle to the man who fought for independence for his country and against all odds, emerged from the bush with a para-military fatigue and exchanged that for designer continental suits in the presidential palace. I just hope he does not exchange those for a prisoner’s drab uniform in the twilight of his life.

In a shocking irony, Mugabe’s instrument of political repression has also become his undoing. For some 37 years, Mugabe relied on the army to do his dirty work for him. It tortured and repressed his political opponents and ensured his absolute one-man rule. With the army firmly behind him, he fell for the temptation that he was destined to last until death did him and power part.

Whether the military action leads to a full-blown military rule or not, the country has entered a post-Mugabe era. What it makes of that era is a more serious matter of the moment than wasting tears on a man who routinely caused many in his country to weep. Mugabe lingered in power for too long for his own good. His well-laid plan to institute a Mugabe political dynasty in Zimbabwe with his wife Grace positioned to succeed him as president has, as poet Robert Browning would put it, gone badly wrong.

Each time an African big man is reduced to a Lilliputian, the rest of us laugh or chuckle. Pay back time is quite often exciting for those not at the receiving end. But we cannot but laugh only to weep for the continent that breeds the African Big Men. I suggest that African sociologists should undertake a comprehensive study of what is in power that beguiles our leaders and makes them cling to it until, for some, they meet a wretched end that effectively buries the good they did for their people.

I was in Zimbabwe in February 2000 as part of the UN monitoring group on Mugabe’s several attempts to rewrite the constitution to suit himself. The referendum was held February 12 and 13 on a proposed new constitution. Its most controversial clause was its proposal to remove a term limit for the president. And this after Mugabe had been in power for 20 years. He thought the proposed amendment was in the bag. Wrong. The people shocked him. They gave the thumbs down to the new constitution. Still, the strong man went ahead to trample under foot the will of the people. His, and only his will prevailed. He continued in office until November 15 when he was suddenly confronted with the elementary fact that only the gods last forever.

It would be unfair to deny that Mugabe offered his people good leadership in the early years of his rule. He inherited a country that was once a pariah when Ian Smith unilaterally declared its independence from Britain. He fairly managed, with mixed results, a multi-racial country in which the former oppressors had become subordinated to the formerly oppressed.

Everything changed when Mugabe succumbed to the temptations of power as he inched his way up the ladder of absolute power. In an emotional huff intended to shore up his flagging rule, Mugabe instituted a land redistribution policy that dispossessed the white farmers of their land. They were forced to leave the country. They took away with them their agricultural expertise that made agriculture the mainstay of the economy. Mugabe ruined the economy in the process with inflation rising to more than 1,000 per cent. The currency was not worth the paper it was printed on. The country has been struggling since then to come to terms with land that is invariably useless to its new owners and contributes nothing to the national economy.

In 2009, Mugabe lost the presidential election to Morgan Tsavangirai, one of the country’s shining political stars, but refused to concede defeat. In a deal brokered by South Africa, he appointed Tsavangirai prime minister between 2009 and 2013. The deal collapsed. The idea of anyone sharing power with Mugabe was positively repugnant to him.

In 2013, Mugabe proposed a new constitution, this time placing a term limit of two terms of five years each on the president – post Mugabe, of course. He was not motivated by the good of the country but rather by the fact that with mortality staring him in the face, he thought it would be unwise to let his successor enjoy no term limit. This time, in the referendum held on the proposal new constitution, on March 16-17, about 95 per cent of the people gave the proposal the thumbs up.

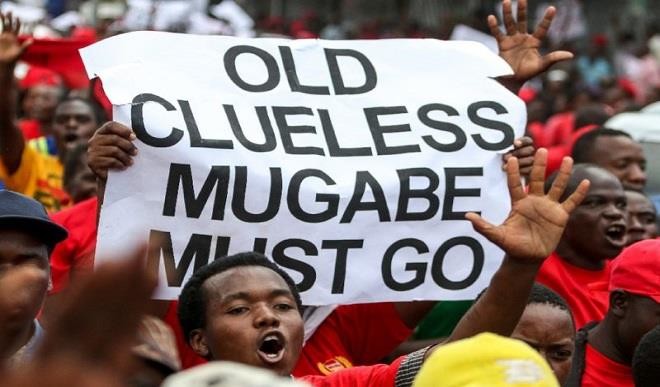

Absolute rulers always tend to believe that they are popular. They believe that if anything happens to them the people would pour out on the streets in protests. It never happens because absolute rule is absolutely stifling of individual rights, liberty and freedom. I am sure Mugabe, in his new luxurious prison, has been listening for evidence that the action by the army is unacceptable to the people. He does not appreciate how much the people welcome his ouster. He said on Thursday that he remained “the only legitimate leader” of his country. He must have been jolted by the statement by more than 100 civil society groups asking him to peacefully come down from his high horse, accept that his time is up and negotiate his place of exile.

It is a wretched end for the man once hailed for his patriotic credentials. He plotted his permanent hold on power. He lost the gamble because the gods don’t fancy those who play God.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.