Intro: After his grandfather amassed a small fortune (and then lost it all) panning for gold, a young prospector heads to Canada’s Yukon Territory in hopes of striking it rich.

Crouching above the frigid waters that race down Bonanza Creek, one of many streams that feed the mighty Klondike River in north-west Canada’s Yukon Territory, I stared into the bottom of a rusted metal pan, hoping to spot something shiny among the sediment.

I had come to this isolated pocket of Canada to write about a local gold-panning world champion. But what I was really hoping for was some of my grandfather’s good luck. In his lifetime, he amassed a sizeable sum (and then lost it all) panning for gold. If I could channel just an ounce of his prosperous spirit, I’d be leaving a richer man.

With my patience running thin, I did my best to employ a method I learned in Dawson City, a nearby mining town where gold was first discovered in 1896. The trick, a local explained to me, was to tilt the pan back and forth and create tiny ripples across the surface. These undulations help the valuable metal break away from the dirt. The murky, coffee-coloured mixture, which comprised a few scoops of dirt and river water, swirled around the surface of my plate-sized saucer before splashing down between my legs. No matter how methodically I swished the contents of my pan, only clumps of mud remained.

Overhead, dark, bloated clouds swallowed the spring sky and sent tiny pellets of hail hurling in my direction. When a gust of wind kicked off my hat, the festive optimism of the day slithered downstream with it. Resigned, I tossed my muddy boots, along with my dignity, into the trunk of my rental car.

My maternal grandfather, Eugene, was more fastidious than me. He pursued his lifelong dream of becoming a gold prospector for decades, not just one afternoon. To him, mining was more than just a hobby; it was his ticket out of a poor, immigrant upbringing in St Louis, Missouri. Anyone with grit and perseverance could do it, he believed, and it didn’t require a high school diploma – something he never obtained.

I only knew my grandfather during his twilight years, when the struggles of his childhood were recited to us grandkids like fables. A son of Polish immigrants, Eugene dropped out of school so he could work and help support his parents and three siblings. He worked as a porter at St Louis’ Union Station and delivered newspapers to his neighbourhood, earning cents for a day’s work. A child of the Great Depression, he never lost sight of the value of money, even in its smallest amounts.

In 1962, Eugene moved his wife and daughter (my mother) from St Louis to California when he heard miners were discovering gold along the banks of the Feather River in the Sacramento Valley. Soon after, he began taking annual expeditions to this mineral-rich waterway, where he hauled bulky equipment down steep canyon trails and sifted through endless pounds of sediment and bedrock. In between these pilgrimages, he stayed closer to his home and panned in the riverbeds of the East Fork River in southern California’s Azusa Canyon.

Family members, including my mother, often got lassoed into his grand agenda, but no-one matched his passion. He hoarded stacks of trade magazines that littered his dining room table and scoured their pages for information on new products and land claims. These publications provided him a portal into a distant land: Canada’s Klondike River. For gold prospectors, the Klondike was the industry’s Mecca. It was a place where claim owners were still finding gold decades after it was discovered.

My mother found his prized collection of magazines in a hallway after his death, and over her lifetime she witnessed her father’s gold fever escalate from a part-time hobby to a full-blown obsession. “The Klondike was too far, but the California Gold Rush, that was doable,” my mother told me. “That would be a more feasible way to find his riches.”

His strategy to stay in California paid off. On a land claim he purchased in Amador County, he discovered a nugget the size of a drawing pin during one of his early expeditions, and it inspired him to keep digging. “If there was a canyon, a river, there must be gold,” my mother said.

He returned to that spot year after year, collecting jars and coffee cans filled with black sand and the precious metal. He’d melt down whatever gold dust, flakes and grains he’d find into larger pieces, and when I was born, he gave my mother an ounce of raw gold that she could pass on to me someday.

In his first two years on the river, Eugene dug up roughly $5,000 worth of gold – the equivalent of more than $41,000 today. But as the years wore on, more money was going into the ground than coming out of it. His equipment needed constant repairs, and transportation to and from these remote canyons became increasingly costly. He even started scuba diving, hoping that if he went deeper into the riverbeds, there would be more to find.

The industry was also changing. Large, industrialised dredging machines were sucking up all the gold, and Eugene loathed the end of ‘Mom-and-Pop’ operators, who, like him, preferred to do most of their panning by hand. He chronicled his frustrations and the difficulties he faced in handwritten letters to my grandmother, his ‘Little Eagle’.

“Finally the rain is over,” he wrote in a letter dated 26 August 1976. “We moved to another beautiful bedrock upstream. Two big boulders could fall or slide and trap us.” In the crease of the letter, as if justifying to my grandmother that the mission was still worth it, he wrote, “Got some nuggets”.

Eventually he bought a local jewellery shop, where he worked as a watchmaker while my grandma managed the books. Together, they bought and sold scrap gold necklaces, tennis bracelets, coins and even dental fillings. For my grandpa, it was a small way for him to remain tethered to his passion. He longed for the days of being outdoors, and above his workbench he hung a photo of his favourite place: the Feather River.

“He did what he could to stay connected to it,” my mother said, as we thumbed through his old, faded photographs and letters she found in an album.

My grandfather’s tall tales of hiking into the Sierra Nevada mountains and camping on unnamed beaches made their way so often around the dinner table that we still recite them to this day – like the time his gear had to be helicoptered down into his campsite, rather than abort the mission altogether. Being on the river gave him a sense of self and belonging he searched for his entire life.

“There was this deep-seated void that I cannot explain to you,” my mother said. “I just lived through it.”

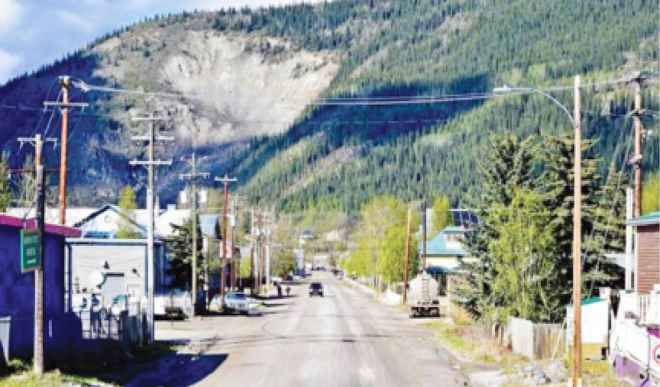

My journey into my familial past began in Whitehorse, Yukon’s largest city, where I drove north along the Klondike Highway, tracing the edges of the Yukon River and the historical route miners first took when they arrived to the region by steamboats. Alone in my car, I marvelled at the endless mountain vistas that were waking up from their long winter’s freeze and rivers that were slowly breaking free, ready to flow into a new season. Soon, the frosty weather would melt under the midnight sun, and the gold-mining industry – which still makes up the largest portion of the local economy – would spring to life.

On the outskirts of Dawson City, the host of my homestay, Kim, flagged me down when she saw me heading in the wrong direction past her house. It was obvious I wasn’t from around here and she knew it.

“It’s the northern way to help those who might be lost,” she said. Coming from the US, where we’re taught to run from strangers, this was a welcome change.

I was staying in a yurt on her property, and from inside my tent I could hear the rush of the Klondike 5m away down a sloped bank. I asked if I could dip my feet in, but Kim shot me down. “Don’t try to cross it,” she warned.

Kim explained that erosion was eating away at the sandbank below her property, and the river was carving a new path for itself. Many people in the area had to be prepared to move their homes, or lose them for good. The river liked to keep residents on their toes.

The next morning, I tossed some change into the coin-operated showers behind the Bonanza Gold Motel & RV Park. A trickle of water ran across my palm and a dirt clod at the bottom of the stall dissolved into the drain. The main entrance advertised free wi-fi and hot breakfast, and the car park was jam-packed with trucks loaded with bulky metal apparatuses, their tyres caked and splattered in mud. I could tell this roadside motel served as a home-away-from-home for those who worked the nearby goldfields.

It was May and early in the summer mining season, but mountainsides had already been sliced open, exposed like open wounds, and large spots in the forest were wiped clear. Soon, the 125 mining operations that are active in the Klondike region would be humming around the clock with cranes and bulldozers digging deep into the ground.

I imagined the appeal of showing up to work in a place like this. Free from the confines of a corporate environment, my office would be in the middle of spruce forests. Every day, I could get lost staring into a sea of green instead of a computer screen.

I followed the winding curves of Bonanza Creek until I reached Claim 33, a museum and local gold-panning business, where I spotted a handful of children holding plastic dishes. They were standing in front of deep troughs of water with smiles draped across their faces, preparing for their first chance at finding gold.

When I was their age, my brother and I learned to pan for gold the same way at a country-western amusement park. Our grandparents had beamed with pride when we walked away with miniature vials filled with the tiniest flakes of gold. I stored mine on a bookshelf in my bedroom, turning it every day to make sure my golden discoveries didn’t disappear.

Across the car park, old miner cabins and vintage storefronts stood side by side, like a ghost town that had somehow been preserved. Littered throughout the yard was a collection of antique mining equipment, left behind by private prospectors from my grandfather’s generation.

I stepped inside the shop and museum, opened the guestbook and scribbled, “To Eugene, a man who always dreamed of coming to the Klondike.” After browsing the aisles of found objects and looking at old photographs of the region, I made my way out, but not before an employee asked me, “Excuse me, are you Eugene?”

I couldn’t help but laugh. After spending the last two days channelling my grandfather, it was funny that the employee misunderstood my note and thought I was actually him. I explained the mix-up. No, I was not Eugene. He died almost 20 years ago, I told her. Though we shared a lot in common, like our stubborn nature and glassy blue eyes, I didn’t have the knack for finding gold like he did. Before long, we were exchanging stories about my family’s past and my grandfather’s lifelong dream of seeing the Klondike. She told me about Claim 33’s former owner, who died in 2009 as one of the region’s last hand-panners.

“Just like my grandfather,” I told her. She nudged me to try panning one more time before I left, but I declined.

It was a foolish notion for me to believe that because of my family’s history I would somehow have a magical touch. My grandfather had spent years perfecting his craft, just like the miners who uprooted their families and dedicated their lives to this profession. After being here, seeing all this, I respected his drive and passion even more.

But I wasn’t leaving Dawson empty-handed. Gold runs in my blood, I realised, and that was more valuable than anything I could discover at the bottom of a riverbed.

Source: bbc.com

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.