Several English words have complex, intriguing etymological heritage, as the examples below illustrate:

1. “Alcohol”: Although alcohol is forbidden in Islam (and Arabic is Islam’s holy language), “alcohol” traces descent from an Arabic lexical ancestor. But it isn’t what you think. The Arabic al-kuhul, from where “alcohol” is descended, didn’t initially mean a kind of beverage that causes intoxication; it meant “the fine metallic powder used to darken the eyelids.” It is derived from the Arabic root word kahala, which means “to stain, paint.”

When the word first entered English in the 1540s, it appeared as alcofol, and meant “fine powder produced by sublimation,” ultimately from Medieval Latin where“alcohol” meant “powdered ore of antimony.”For several years since the 1540s, alcohol signified “powdered cosmetic.”

So how did “powdered cosmetic” come to mean an intoxicant in later years? Well, the semantic shift occurred around the 1670s. At this time, alcohol’s signification expanded to include “any sublimated substance, the pure spirit of anything,” including fluid matter. By 1753, the modern meaning of alcohol as a synonym for“intoxicant” took firm roots. It started as the short form of “alcohol of wine,” which, according to the Online Etymology Dictionary, was extended to “the intoxicating element in fermented liquors.”

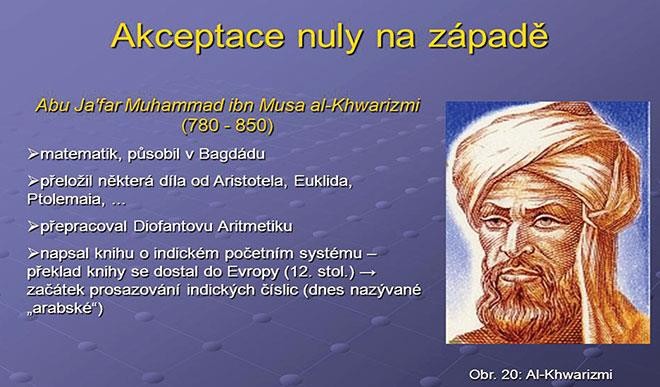

2. “Algebra”: The word came to English in the 1550s from the Latin algebra, but Latin borrowed it from the Arabic al jabr, which literally means “reunion of broken parts.” The word was popularized in the 9th century by a Bagdad-born Persian Muslim mathematician by the name of Abu Ja’far Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi whose last name is the source of the word “algorithm” (see my four-part series titled “Top 30 Common English Words That Are Derived from Names of People” published on April 28, 2013, May 5, 2013, May 12, 2013, and May 19, 2013). Al-Khwarizmi wrote a celebrated book on mathematical equations titled “Kitab al-Jabrw’al-Muqabala,” which, according to the Online Etymology Dictionary, “also introduced Arabic numerals to the West.” Without Arabic numerals, complex mathematical calculations (and therefore science and technology) would be extremely hard at best and impossible at worst.

3. “Checkmate”: Many respected etymologists say checkmate comes from shah mat, which they say is Arabic for “the king is dead.” But that’s not entirely correct. It seems more likely that checkmate actually comes from the Persian (also called Farsi) “shah maat,” which means “the King is surprised.” Shah means king in Persian (Farsi). The Arabic word for king is “malik.” While “maat” means “dead” in Arabic, it means “surprised” in Persian (Farsi). Whatever the case, “checkmate” has Middle Eastern origins.

4. “Bless you”: An aggressive American atheist colleague of mine with whom I shared an office when I was a Ph.D. student used to resent people saying “bless you” to her when she sneezed. She thought the expression was Christian. She preferred “Gesundheit,” the secular, polite response to sneezing in German-speaking countries, which is also popular in the United States, especially among secular humanists. Well, it turns out that “bless you” is actually not Christian in origins. It came from European, specifically German, paganism. It originated from the German expression “blessen,” which means “mark with blood.” In German pagan tradition, as in so many other pagan traditions, blood symbolizes consecration, holiness, or blessing.

5. Cushy: This word means easy, soft, not demanding, done easily. So a “cushy job” is a job that is financially rewarding but doesn’t require much mental or physical effort, such as being a member of Nigeria’s useless National Assembly. There is a popular folk etymology that traces the roots of “cushy” to “cushion”- from the Anglo-French word “cussin,” which is itself derived from the Latin “coxa,” which means “hip.” But that’s false. It is the word “cushion” (a soft place where one sits with one’s hips, such as a chair) that is descended from cussin via coxa.

Cushy is an entirely different word that came to English via Urdu, the official language of Pakistan, which shares linguistic ancestry with Hindi, although it’s written in Arabic script. In Urdu, “kusi” means“easy or comfortable.” It entered English during the First World War when men who served in the British Army heard it from Urdu speakers in India (before it was partitioned into Pakistan and India in the 1940s and later Bangladesh in 1971) and brought it back to their homeland as “cushy.”

6. Girl: Girl didn’t always mean a female human offspring. When it first emerged in English, “girl”meant any young person, irrespective of gender. It comes from the Middle English word gyrle, which meant “child” or “youth” of both genders. That meaning of the word can be gleaned from English poet Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales where reference is made to the “yongegyrles of the diocese,” which would translate as the“young children of the diocese” in modern English.

7. Goodbye: This everyday farewell remark we utter when we depart from people emerged from a contraction of “God be with ye” (“ye” was second person plural pronoun in English, equivalent to the modern “you.”) It became mainstream in English since the 1300s. There is a parallel example of the contraction of a phrase into a word taking place in contemporary informal English with “sup?” which started as “what is up?” then became “what’s up?” and then “wassup?” before morphing to “sup?”

8. Meat: Meat meant food in general, a meaning that survives in the adage “one man’s meat is another man’s poison.”

9. Mortgage: Mortgage etymologically means “dead pledge,” which is kind of scary. In Old French (i.e., the earlier form of the language spoken from the 9th to the 15th centuries), “mort” meant “dead” and “gage” meant “pledge.” This morbid sense of the word’s meaning survives in the expression “mortgage your children’s future.”

10. Sabotage: Sabotage comes from the Old French word “sabot,” which meant a wooden shoe. During industrial disputes in factories, workers used to throw shoes at machinery in order to damage them. In time, deliberate damage to property came to be known as sabotage.

11. Silly: When silly first appeared in English lexicon in Old English, that is, English spoken before 1100, it meant “fortunate,”“happy,”“prosperous,”“lucky.” By the 1200s, the word came to mean “blessed,” “pious,” “innocent.”The word changed meaning again, by the 1300s, to “harmless,” “pitiable,” and later “weak.” The word’s current meaning of “feeble in mind, lacking in reason, foolish” started in the 1570s. According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, “Further tendency toward ‘stunned, dazed as by a blow’,” as in “knocked silly” started in 1886, and that“Silly season in journalism slang is from 1861 (August and September, when newspapers compensate for a lack of hard news by filling up with trivial stories).”

12. Sinister: This word for evil initially meant “left,” as in “left hand,” in Latin. The left hand was (and still is) generally thought to be weaker than the right hand. That’s why the opposite of sinister was “dexter,” which means right hand. That’s also why “dexterous” now means skilful, adept, expert, agile, etc.

Like most African cultures, Romans, influenced by Greeks, also thought the left hand portended evil and misfortune. That’s where the current meaning of sinister as evil comes from. Many thesauruses still list “sinister” and “left” as synonyms. A UK student who wanted to conceal his plagiarism of a paper through mindless synonymizing (called Rogetism, after the famous Roget’s Thesaurus) synonymized the expression “left behind” as “sinister buttocks” because the thesaurus he consulted showed that “sinister” is synonymous with “left,” and “buttocks” is synonymous with “behind”!

14. Tragedy: “Tragedy” is descended from the Greek tragodia, which literally means“goat song.” “Tragos”means “goat” and “oide” means “song.”Ancient Greeks thought the bleat of male goats inspired sadness. I can attest to that. I am writing this column from my hometown of Okuta in Baruten local government area of Kwara State in north central Nigeria where goats are bleating everywhere in ways that inspire sadness.

15. Villain: In modern English, we know this word to mean an evil, wicked person. But it didn’t always mean that. When it entered English in the 12th century via French, it meant “peasant, farmer, commoner, churl, yokel.” The word’s roots are traceable to the Latin “villa,” which meant “country house, farm.” It later morphed to “villanus” in Medieval Latin and meant “farmhand.” That’s the meaning English inherited in the 12th century. By 1822 the word underwent a semantic shift. It started to mean the chief bad character in a film or work of fiction. Now it also means any evil person. So the word went from meaning a farmer to an evil person in the space of about six centuries.

16. Zero: This word has a fascinatingly circuitous history in English. It entered English via French (some scholars say it’s via Italian, but both French and Italian are Romance languages that are descended from Vulgar Latin). The word came to Romance languages (that is, French, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, etc.) through Arabic by way of the Muslim conquest of Spain-and the cultural and linguistic reverberations it has had in (southern) Europe.

Ultimately, however, Arabic borrowed the word from Sanskrit, an ancient language from where Hindi and many languages in the Indian subcontinent are descended. It initially appeared as“sunya” in Sanskrit and meant “nothing” or “desert.” As many scientists know, there would be no mathematics and, therefore, no science and technology, without zero.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.