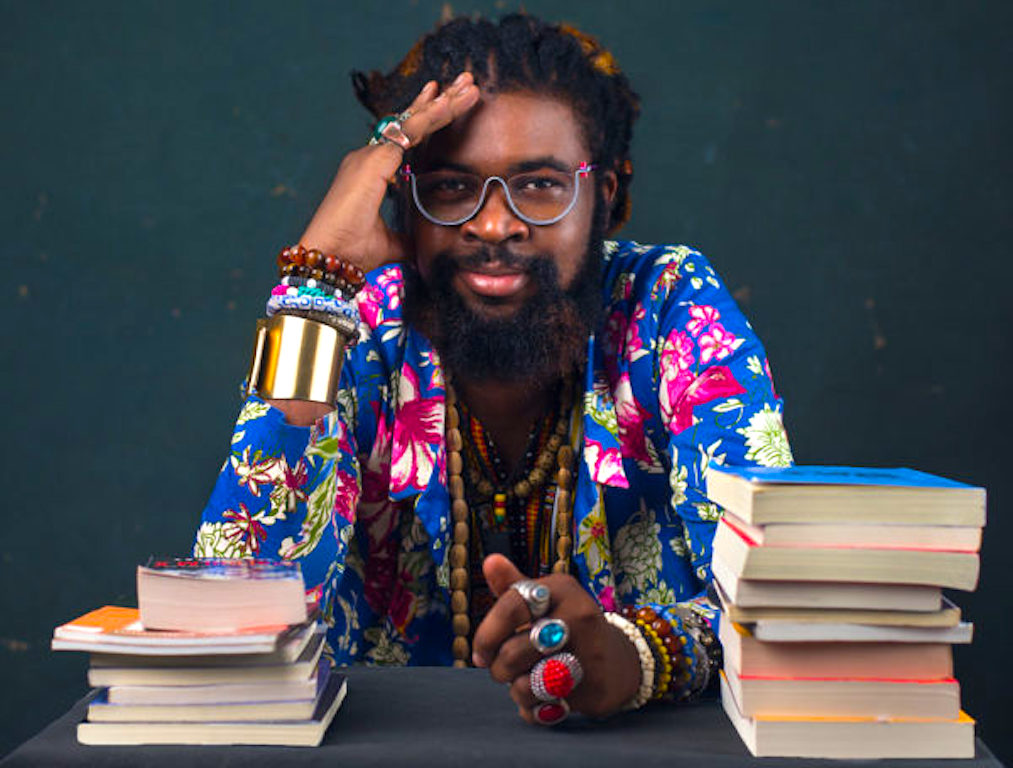

When the story broke out, I was one of the first to cast doubt on the claim that Mr. Nwelue paraded himself falsely as an academic professor at Oxford and Cambridge, two distinguished universities at which the maverick had functioned as an Academic Visitor. Mr. Nwelue had always been vocal about his “dropout” status to the point of referencing it to assert his literary genius. His pride in achieving firm footing in the literary realm after dropping out of a Sociology programme at the University of Nigeria is almost akin to how Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg market their lack of academic credentials.

That a Nobel laureate, in a field in which Mr. Nwelue made his name, had to intervene is a measure of the younger writer’s place in our literary space. Professor Wole Soyinka wasn’t only alarmed by the twisted justice dispensed by the digital mob that pounced on Mr. Nwelue, but also by the extremism of the publishers and agents that mailed to terminate their relationship with him. “The charges against this author do not involve plagiarism or other literary offenses, nor any crime against humanity,” argued Soyinka. This is a valid inquiry in a world where even mass murderers secure deals to document their experiences, and it has fueled the clash of opposites that has made the publishing world an engine room of ideas.

Mr. Nwelue’s nightmare is a tragically hijacked conversation that began with a student-run blog at Oxford University. The blog disseminated sensationalised accounts of Mr. Nwelue’s social media activities and concluded that he is guilty of impersonation, misogyny, classism and racism. The weight of these allegations is enough to force even Mr. Nwelue’s closest allies and friends to keep their distance, but doing so would deprive the manifest scandal of the nuances it seeks.

Mr. Nwelue’s worst undoing is his polarising digital identity. He’s fiercely antagonised by those offended by his unfiltered and provocative views. On Facebook, I was fond of countering his serialised mockery of “poor people,” which I interpreted as mostly dark humour, reminding him, albeit playfully, that I was a poor yet dignified man. It was a banter I never took as scandalous until they were documented as evidence of his classism by the student-run blog and the compliant social media mob that has feasted on the story.

- Ministers hand over ahead of cabinet dissolution

- NIGERIA DAILY: Who Will Save Nigeria From Losing Its Doctors?

I find Onyeka’s travails unfortunate because I have followed him from a distance and closely for about a decade and a half, convinced that he couldn’t have meant the provocative and eccentric things he said. If you know him in person, you would think so too. He is the opposite of the things he says online, and it’s disheartening that he has found himself in a situation where he’s struggling to prove that his “sexist,” “racist,” and “classist” views are, as he admitted in an interview with the Oxford student-run newspaper, “…a social experiment to get feedback for a book I was working on.”

As a public figure functioning in institutions reputed for methodical knowledge production, he ought to have read the room—and should never have been put on trial by powerful platforms like the British literary establishment. His case has seemed unwinnable because of the guilt of association with David Hundeyin, whose presence at Oxford as a guest of the fellowship, Mr. Nwelue managed on the campus fueled this maddening rage that has forced one of them out of social media, and the other fighting to prove that Malam Nasir El-Rufai owns Oxford.

At the inaugural James Curry Literary Festival on the Oxford campus, a few writers of northern Nigerian extraction attempted to criticise the organisation as sectional, accusing Mr. Nwelue, who invested his personal resources to host the event, of inviting only writers from the Southern part of Nigeria. I came to his defence. Firstly, most of the “southern” writers in attendance lived around the venue, and even my good friend, Suleiman Ahmed, a Kogi-born writer and software developer, made it to the festival. He lives in the UK.

In 2011, Mr. Nwelue organised what I would present without any fear of contradiction as the only literary festival in Nigeria in which invitations weren’t based on cliques. He had never met or had a relationship with most of the guests invited and only chose them based on the recommendation of his team. The Bayelsa Book and Craft Fair was a beautiful confluence of writers from the North and the South, and I cited this pan-Nigerian leaning to counter the attempt to accuse him of anti-North bias.

In October 2020, after I was brutalised by the most nihilistic cops I have ever come across at the #EndSARS protest in Abuja, with my phone destroyed, Onyeka, who had disappeared from social media, wrote me an email with the subject “Checking…” just to say, “How are you, my brother? I hope you are safe and sound? Do you have a WhatsApp number? I read something in Premium Times and thought to check up… Regards.” It was a touching gesture that underlined his humanity, which is often played down by those with no idea or context of his life.

Whatever is said about Onyeka, his transition from being a self-proclaimed college dropout teased as “Prof” or “Professor” to becoming the subject of impersonation investigations at two of the world’s oldest universities is not of his making. He is self-advertised, famous, and well-documented as a dropout. It’s also easy for one to think he’s just a titular professor, a rank probably earned because of his teaching engagements at the institutions he advertised on his social media pages. One wouldn’t have expected Oxbridge to seek his services without a background check, and a single Google search is enough to reveal what he never hid in the first place.

As a graduate student at the LSE, I was part of a team tasked with inviting guests to the student-run summit, and I recommended one guest who was dismissed after a Google single search. The recommended guest, a notable public servant who had been at war with the Nigerian government and faced vicious smear campaigns, was disqualified because of a Google search that referred to him as corrupt. It didn’t matter that there was no court litigation or conviction to justify their conclusion. Oxford or Cambridge couldn’t have claimed they had no access to the internet when making the decision to invite Mr. Nwelue to bask in their halo because that would be the actual scandal.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.