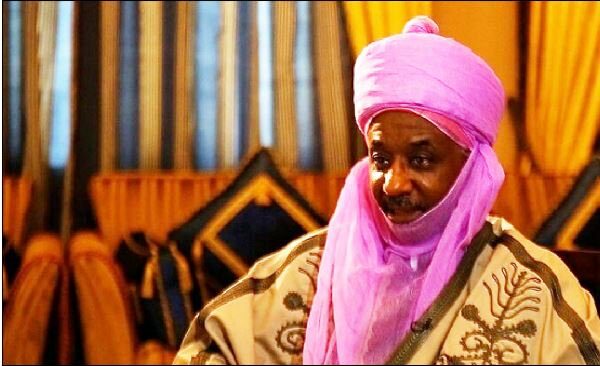

One of the stirring messages from the seventh edition of the Kaduna Economic and Investment Summit, which was held in Kaduna last week, was Emir Muhammadu Sanusi II’s appeal to Nigerians. The 14th Emir of Kano, as he once asked us to call him at one of such gatherings, asked Nigerians to prepare for the hard times ahead in their bid to elect a new president. Emir Sanusi’s guided cynicism was inspired by the fiscal and monetary disasters of the past years, and his caveat was unambiguous: “Anybody that tells you it’s going to be easy, please don’t vote for him. Because it’s either he’s lying to you or he does not know what job he’s going to get.”

Emir Sanusi’s advice probably came about eight years too late and could’ve passed for the mockery of the Nigerians who partook in the mass hysteria of the 2015 elections, when Buhari was packaged as a frugal and incorruptible saviour of the common man. But it’s still a timely reminder for those who process realities slowly and willing to redeem their past choices. Nigeria is a perpetually-misdiagnosed problem, and none is as troubling as the claim that the country needs a Moses to part the sea between the people and their development.

- Nigeria, OPEC countries back 2m barrel crude oil cut

- NIGERIA DAILY: Why Nigeria May Lose Its Position As “Giant Of Africa” In Next 10 Years

Our worst mistake has always been this mindset that Emir Sanusi underlined in his speech at Kaduna—that belief that Nigeria needs a messiah, a strongman or a self-styled national hero to fix its problems without ruffling a feather. This has led to our perpetual search for heroes even where there are none. Buhari himself is a creation of such thinking. There are no messiahs anywhere, only unified fronts towards a common goal or a set objective.

We can’t keep on manufacturing fallible heroes to solve problems for which institutions exist and expect the miracle we imagine to transpire. Even the most honest individuals are short-lived reprieve in policy-making. They are mostly untreated bandage on a wound that requires immediate and methodical surgeries. Even if that individual were Chief Obafemi Awolowo who, unlike Buhari, did not secure the opportunity to demystify himself in power and got to retain his honour as the “best president Nigeria never had.”

We tend to relegate the miracle that a vigilant and unified citizenry can perform, and that’s much more effective in nation-building than this illusion of a messiah. Whoever we lionise and elevate as our hero is also human, driven by sentiments and emotions, some of which are for personal interests. This has played out too many times it should be irremissible for any Nigerian to fall for a self-advertised messiah again.

The hardship for which we are being asked to prepare by the erudite economist and former CBN governor is one that no messiah can prevent. Whatever palliative interventions promised by the political candidates running for office in 2023 can’t be sufficient for the possible outcomes of the difficult economic decisions staring us in the face, one that the pseudo-populist charlatans in the corridors of power have exploited for campaigns but incapable of implementing. Nigeria can’t afford a long-running tea party, but the steps towards to adjusting to this reality must begin with the president.

The incoming occupants of Aso Villa, and the citizens too, have no option better than preparing for the economic surgeries ahead. This is much nobler than the contest to glorify flawed messiahs every election year. Any national problem that revolves around the wisdom of a so-called messiah—instead of an existing or established institution—is bound to fail. No public policy should ever drive its soul from the heartbeat of any self-styled strongman. Nigerians must unite to harmonise their ideas and advocate their implementations as a group. They are messiahs who must dictate the tunes they wish to hear next year.

The economics of fuel subsidy is a lesson on the futility of messiahs, and it’s the tricky part of the reforms before Nigeria’s next leader. Buhari rode to power in 2015 dismissing the subsidy regime as a political smokescreen only to find himself overwhelmed by its mathematical realities and a country eager to question his past claim that subsidy was a grand fiction to hoodwink Nigerians. He went from the political candidate who famously cast doubt on the existence of fuel subsidy to an informed president struggling to find a less-disastrous solution to oil pricing in a period of global oil price instability. But the subsidy removal, for him, wasn’t just about the economic crisis to expect; it’s woven around a troubling moral crisis for a leader who’s been elevated as a symbol of integrity and hailed elsewhere as “Mai Gaskiya”—the honest.

Perhaps, that’s why the vice president was tasked to serve as the first vocal evangelist of subsidy removal a few months after they took power. He was quick to acknowledge the “various observations about the fuel pricing regime and the attendant issues generated”, and that dissenting Nigerians who objected to the removal “have all certainly raised strong points”, before hinting the country about a proposed scheme for mitigating the impacts of their forthcoming solution on the poor in 2016.

The vice president also noted in the alarming speech that “the most important issue of course is how to shield the poor from the worst effects of the policy.” This was quite amusing then, coming from an administration that had made a remorseless u-turn on all the welfarist programmes it promised before the elections, from meals for public schools to N5000 stipends for the unemployed graduates.

The fear of hard times was the central concern of Osinbajo’s speech on the fuel pricing regime barely a year through their first tenure, which also revealed that: one, the federal government had exhausted its ideas on the way to redeem the economy, and subsidy removal was the only option left; two, Osinbajo’s speech was only intended to serve as a damage control; and three, withholding details of the federal government’s promised welfarist scheme suggests the subsidy removal was a hastily concluded policy since the economic statistics and dilemmas revealed by the VP were a rehash of known arguments advanced by “anti-subsidy advocates.”

Even if Emir Sanusi II’s caveat for Nigerians didn’t ring loud enough to prepare the voting citizens to acknowledge that there’s no messiah in the race to Aso Rock, but pragmatic leaders who can make the difficult decisions at the right time, the neglect of some of the welfare packages promised by the Buhari/Osinbajo ticket is enough reminder that the promise of a messiah is a grand illusion.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.