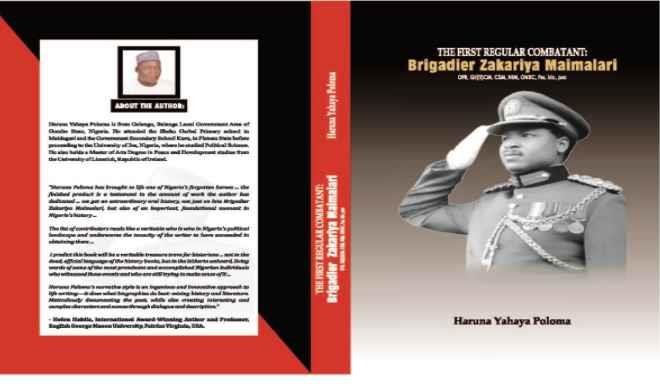

A review by Prof. Helon Habila

In his biography of the late Brigadier Zakariya Maimalari, Haruna Poloma has brought to life one of Nigeria’s forgotten heroes. This is an ambitious book, over fifteen years in the making – the author began working on the book in 1999 – and the finished product is a testament to the amount of work the author dedicated to his task. Perhaps the most singular thing about the book is its form, its “anthological style”. Each chapter is a reminiscence by an acquaintance, a friend, or a professional colleague of the late Maimalari, and from these reminiscences and anecdotes we get an extraordinary oral history not just of the subject, but also of an important, foundational moment in Nigeria’s history. Each account, each chapter, works like a piece in a puzzle, together creating a total picture.

The list of contributors reads like a veritable who is who in Nigeria’s political landscape and underscores the tenacity of the writer to have succeeded in obtaining them. They range from former rulers of Nigeria like Gen. Yakubu Gowon, who personally wrote the Foreword, to former President Olusegun Obasanjo, President Muhammadu Buhari, Generals Ibrahim Babangida and Abulsalami Abuhakar, who were all junior officers under Maimalari,to Ambassador Yusuf Maitama Sule, Justice Mamman Nasir and Lawal Kaita who were school mates of Maimalari at Barewa College, Zaria. Others include Generals Emmanuel Abisoye, Alani Akinrinade, Muhammadu Inuwa Wushishi, Joseph Garba, Paul Tarfa, Garba Duba, Rowland Ogbonna, Muhammadu Bashir Iliyasu (Muhammadu Jega), Ike Nwachukwu, and David Jemibewon, just to mention a few among Nigeria’s military top brass. And these are among the ones who made it into the book. Others, like fmr President Shehu Shagari, who was interviewed by the author, didn’t make it into the book for technical reasons (the recorded interview got damaged and couldn’t be retrieved); or because they didn’t want to go on record (Major General Mamman Shuwa). Others like the late Odumegwu Ojukwu didn’t make it for logistical reasons. In the author’s own words, “I went all the way to Lagos to interview the late Chief Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu, Ikemba Nnewi, only to be informed that he was expecting me in Enugu!”

Although the accounts do differ, as they must, in particular points and in minor details, what they all agree upon is that Maimalari was not only a patriot, a loyal friend, a great husband and father, a gentleman, he was also the finest officer Nigeria ever produced.

Zakaria Maimalari was born in Maimalari village of Yobe State, after his elementary education he attended Barewa College in Zaria. After college he and a friend of his, Lawan Umar, joined the army in March 1950, and after undergoing preliminary training in Nigeria and Ghana, they went on to the Royal Military Academy in Sandhurst, UK, where they graduated in February 1953 as Second Lieutenants. Zakariya Maimalari and Lawan Umar became the first Africans ever to attend and successfully pass out of the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, in the United Kingdom. And thus the title of the book, “The 1st Regular Combatant”. Maimalari went on to have a stellar career, which included serving in the Congo as a peacekeeper and brigade commander of the 2nd Brigade, Apapa, Lagos. The book abounds with accounts of his kindness, thoughtfulness, and his wit and great sense of humour. Here is one recollection about a certain occasion in the officers Mess, “On this particular night, there was a Lieutenant Shande posted to introduce invited guests to the Commanding Officer, then Lieutenant Colonel Maimalari. There was a young lady among the invited guests whom the Commander had asked:

“What would you like to drink”?

She Replied:

“I would love a Shandy”

The Commanding Officer promptly exclaimed:

“Lieutenant Shande, come here. There is a lady who loves you!”

Brigadier Maimalari’s career was however cut short at the age of 36; he was killed on 15 January 1966 by Junior officers in Nigeria’s first ever coup d’etat. I predict this book will be a veritable treasure trove for historians-reading it one has the impression of eavesdropping on policy makers conversing off-record. It captures these august personages in their most unguarded, and most likely hitherto undocumented moments. It documents a moment in our history when our country had its greatest promise-when the British colonialists were finally packing up to leave, and the Nigerians, young and promising and talented, were stepping into their shoes. It is also the moment when things began to go awry, just a few years after independence came the first ever coup of 1966. But it does so not in the dead, official language of the history books, but in the hitherto unheard, living words of some of the most prominent and accomplished Nigerian individuals who witnessed these events and who are still trying to make sense of it. In elegiac tones we hear Maitama Sule recounting how, after the murder of Maimalari, his neighbors, perhaps for fear of repercussions, refused to look after his family and property, and how Sule volunteered to do it, “When the news got to me, I immediately demanded that they be brought to my house. They were to remain at my house up until the time I left Lagos.”

Many books have been written on the coup of 1966, debates are still carried out over the reasons and causes of it, but perhaps none of these books or debates can evoke the gruesomeness of it better than the perplexed words of one of the contributors:

“How could the plotters kill Ademulegun in bed with his wife? Why did they have to toss a grenade at Ralph Sodeinde while he was in bed with a pregnant wife? What was the rationale behind dragging the bullet-ridden body of Abogo Largema down a staircase? How can one explain the horrendous torture they reportedly inflicted on the late Prime Minister, Sir Abubakar Tafawa-Balewa? It was Major Emmanuel Ifeajuna, the Brigade Major of Zakariya Maimalari, who reportedly killed Zakariya himself. Now I know that if Zakariya loved anyone in the Army, he definitely loved Ifeajuna! So why? Tell me! Why? The coup plotters of 15th January 1966 were simply out of their minds!”

Some of the most touching moments in the book however don’t come from the more famous contributors, but from their wives, or from their servants and junior officers. Haruna Poloma’s narrative style is an ingenious and innovative approach to life writing-it does what biographies do best: mixing history and literature. Meticulously documenting the past, while also creating interesting and complex characters and scenes through dialogue and description.

Helon Habila, Professor, English, George Mason University, Fairfax Virginia. USA.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.