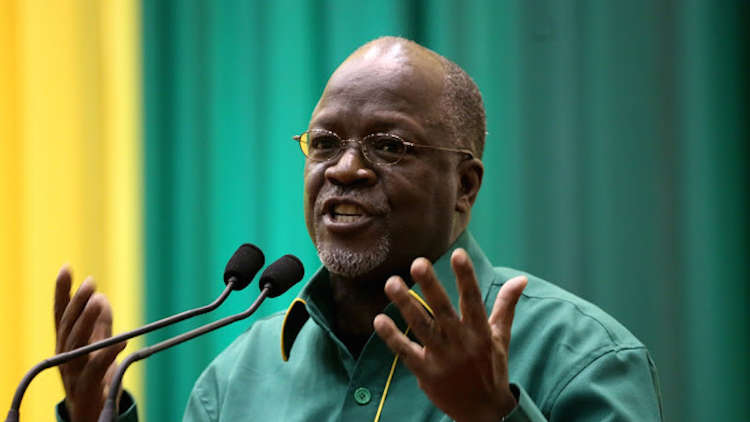

An emotionally charged week in Tanzania culminated on Friday with the burial of the late President John Magufuli.

From offices and pubs, to beauty salons and corner shops, millions of Tanzanians, for days, were glued to the steady stream of images on their television sets showing eulogies and dirges as the coffin of the late leader was carried from the commercial hub of Dar-es-Salaam, through the capital, Dodoma, to his final place of rest, his hometown of Chato.

Throughout, large crowds of mourners thronged the streets and stadiums to bid their last goodbyes to a president who spent much of his tenure roaming the country to meet his constituents.

Often, Magufuli would use these tours to address people’s needs, relying on his power to demand solutions on-the-spot for the citizens’ various complaints. But in other cases, during visits to opposition strongholds, he was known to castigate voters for not backing his ruling CCM party, and was even on record saying he would not resolve residents’ problems in such.

“Magufuli was a complex person to analyse. He left behind a mixed-bag of legacy,” said Jenerali Ulimwengu, a veteran journalist and political commentator. “Was he a control freak? Was he a developmentalist? The debate about his legacy will linger on for a long time.”

On the evening of March 17, then Vice President Hassan appeared on state television to announce that Magufuli was dead and declared two weeks of national mourning. At the time, the president had not been seen in public for more than two weeks. The absence sparked rumours that the 61-year-old was either already dead or lying comatose in a hospital abroad.

Many speculated Magufuli had contracted COVID-19, the disease which outbreak he handled with constant controversy. Hassan instead told the nation the president had died from a chronic heart condition.

But for many, the pandemic is almost certain to be one of the most defining issues of Magufuli’s presidency.

As the coronavirus last year took hold across the globe, Magufuli downplayed its severity and pointedly rejected the idea of locking down. Tanzania officially stopped reporting case numbers in April 2020, remaining open to travellers and without restrictions on social gatherings.

Magufuli also made a number of headline-grabbing statements, including that the virus was a Western hoax and could not survive “in Christ’s body.” He also mocked mask-wearers and told Tanzanians to treat flu-like symptoms with steam inhalation and other traditional herbal medicines.

A former teacher and industrial chemist, Magufuli was known as “the bulldozer” for his no-nonsense approach to building roads during his stints as minister of works (2000-2005 and 2010-2015).

In 2015, he became an unexpected presidential candidate for the CCM, the party that along with its predecessor had uninterruptedly been in power since independence but was rocked at the time by internal divisions and corruption scandals.

Faced with the prospect of defeat, the CCM turned to Magufuli, whose hard-nosed reputation was seen as an antidote to the ignominy that plagued the party’s upper ranks.

Having leap-frogged the political heavyweights, Magufuli went on to win the 2015 election, but the happenstance of his “accidental” presidency did nothing to dampen his vision. Magufuli was impatient to see results, and his zeal to fight corruption and develop Tanzania’s infrastructure is what many will remember him for.

“Death has robbed us of the leader you might have become if our prayers had been answered,” lamented columnist and commentator, Elsie Eyakuze, in an intimate open letter to Magufuli last week.

Since the 1960s, there had been talks of constructing a mega-dam over the Rufiji River, but time and again, the project stalled. Within two years of becoming president, Magufuli had signed off on the blueprints and construction began in 2019, financed not by donors, but by the government.

There is other evidence of the bricks-and-mortars of Magufuli’s time in office, too. Supporters point to the construction of numerous highways and improvements to thousands of feeder-road areas. They also call attention to the country’s first electric railway that is currently being built and credit him with the revival of the national carrier, Air Tanzania.

Consistently, Magufuli made progress, which will continue to affect the lives of millions of Tanzanians for years to come. Yet consistently, he was willing to deploy his constitutional power to curtail civil and political freedoms and bend the law to do his bidding.

During the same period that saw the undertaking of the massive infrastructure projects, Magufuli banned teen mothers from classrooms; outlawed opposition rallies and broadcasting of parliament sessions; and introduced legislation which rolled back civil rights.

At the last election in October 2020, independent observers were effectively locked out, but one observer, Tanzania Election Watch, retrospectively confirmed at least 18 arrests of opposition party officials, as well as “arbitrary arrests, unlawful detention, sexual violence and violence against women.”

The vote, which Magufuli won with 84 per cent, was fiercely contested by opposition figures, who claimed the results were not credible. Members of the international community, including the United Nations, the United States and the European Union, condemned the intimidation and harassment of opposition figures and their supporters, alongside a nationwide internet shutdown.

Meanwhile, many of Magufuli’s multibillion-dollar infrastructure projects were marred by allegations that public procurement procedures were routinely bypassed in the race to complete the projects.

On one hand, Magufuli made it his mission to purge the civil service of corruption, but within few years of his time in office, his sleepy hometown of Chato, with a population of less than 28,000, was transformed by the erection of a regional hospital, an airport and industrial facilities more befitting of an urban centre serving three or four times as many residents.

Ulimwengu points out Magufuli’s contradictory approach to the fight against corruption – he was quick to clamp down on wrongdoing, but also antagonised the controller audit general and the press.

“He shot himself in the foot. By weakening key institutions and making himself at the centre of fight against corruption, he diminished his own power of intervention,” Ulimwengu said.

For the prominent Kenyan economist, David Ndii, there is nothing complex about Magufuli’s legacy. “It’s a bad one,” asserted Ndii.

“Freedom is non-negotiable. Freedom is a fundamental foundation of development. I define development as freedom,” he said.

“This idea that you can develop people while beating them up doesn’t fly,” Ndii added.

Meanwhile, Michaella Collord, junior research fellow in politics in the University of Oxford, urged caution in perceiving the Hassan presidency as a new chapter for Tanzania, arguing that part of Magufuli’s legacy is a continuation of his predecessors’ legacies.

“Even though Magufuli did bring major changes, there was also continuity with the past,” she said.

Similarly, Collord dismissed suggestions that the departure of Magufuli would automatically bring about a fully peaceful and business-friendly democratic environment.

Even if Hassan were to allow for more political contestation within the governing party and for renewed opposition activity, Collord said she believed this would be constrained by the legacy of Tanzania’s authoritarian past, which predates Magufuli’s presidency.

Source: Al Jazeera

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.