When in 2019 Nigerian painter Julius Agbaje depicted President Muhammadu Buhari as the Joker, he never imagined that a year later his portrait would become a symbol of youth protest.

His image, “Joke’s on You,” showing Buhari with a red nose, white makeup and a terrifying smile, was the emblem of demonstrations against police brutality that rocked the country last October.

“At first it was a joke, just a provocation,” the 28-year-old artist said in his tiny studio in a rundown district of Lagos.

“Months after, this piece went viral, and resonated with a lot of youth.”

Even before the Joker image, Agbaje had already earned a place on Nigeria’s vibrant cultural scene. He is also one of its most committed artists.

“I always dare to challenge things, especially wherever there is injustice. I love to be provocative, and art gives me a channel though (which) I could express that vexation, to fight those injustices.”

Nigeria, with its 200 million inhabitants, may well be considered Africa’s largest democracy, but it has barely turned the page on its history of military dictatorships.

More than 20 years after its democratic transition, the country remains plagued by corrupt politics, rampant poverty and violations of basic rights.

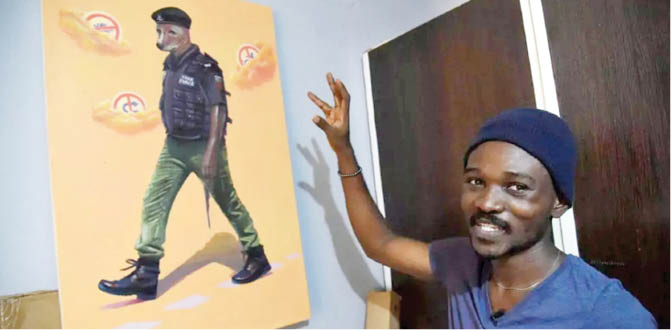

Between acrylic pots and worn brushes, Agbaje rolls out his canvases on the tiled floor of his studio for a visitor.

The “social satirist”, as he likes to call himself, Agbaje knows few taboos.

He learned his craft at the oldest art school in Lagos, the Yaba College of Technology, from where he graduated in 2017.

His dexterity comes to the fore in a portrait made with knives of two monkeys — the figures, wearing police helmets, are seen in mugshots, with signs around their necks saying “murder” and “duplicity & theft”.

The diptych, entitled “Good cop, Bad cop”, was produced long before last year’s #EndSARS protests erupted over police brutality, and forced the government to disband the SARS special police brigade.

The image is now on display at his art school’s museum.

The young artist picked up his brushes again when last year’s youth protest movement was brutally suppressed. Amnesty International said the army opened fire and killed at least 10 people, a charge the military has denied.

Far from his caricatures, they are perhaps his most successful, at least his most poignant.

In Nigeria, there is an abundance of artists who criticise the political system, but many use only abstract images, few do so in such a confrontational way.

Among his influences, Agbaje cites the Nigerian performer Jelili Atiku, who denounced extrajudicial executions for years, leading to his arrest in 2016.

“It’s scary to be honest…, it must be said, because I realise that some people sacrificed before I came,” Agbaje said.

“And because of those sacrifices… I can even enjoy some of this semblance of freedom that I enjoyed today, I feel that is my duty.” (AFP)

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.