“There is nothing which contributes more to the making our undertakings prosperous than the taking of times and opportunities; for time carries with it the seasons of opportunities of business. If you let them slip, all your designs are rendered unsuccessful”.

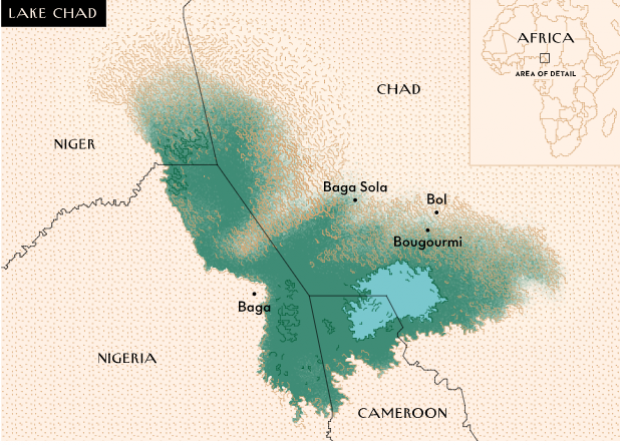

The time has come and the opportunity is available, for the problem of the Lake Chad to be addressed conscientiously. The choice before Nigerians is this – to let “nature” take its course and see to the eventual drying up of the Lake, or, to intervene to sustain it for the future by replenishing it with water from other sources. The issue is both simple and complex in the sense of justifying such a monumental task by executing it with a single-minded determination, or allowing what is avoidable to happen and then submit ourselves to the terrible verdict and ridicule of posterity. I believe every rational consideration will admit the former and discountenance the latter.

It is our duty, as citizens, to prod our elected government towards taking bold measures as would ally our concerns and secure our future by committing to undertake schemes that have direct and immediate bearing on our lives.

Saving the Lake Chad, therefore, must be seen as an existential project the like of which has not presented itself to our country in living memory. Successive administrations particularly the last government of President Muhammadu Buhari, gave every possible attention to the problem of Lake Chad but due to policy fragmentation and challenges of mobilisation of the will and energy of the government, time was squandered and opportunities were missed, for the recharging of the Lake Chad in the eight years that the administration lasted.

The Tinubu-Kashim administration today has both the time and the opportunity to execute the project of recharging Lake Chad within a short period if it chooses to commit itself to this undertaking. The administration has already taken the right steps recently by reconstituting the boards of the 12 River Basin Development Authorities (RBDA) in the country.

With particular reference to Lake Chad, the reconstitution of the Chad Basin Development Authority (CBDA) should provide a fresh impetus toward the reinvigoration of this institution and the revitalisation of all its operations.

The responsibilities facing the new board are onerous and important at the same time. It is not there merely to manage the affairs of the Authority, but to ensure that the purposes for which CBDA was established in the first place are realised, namely to develop the South Chad Irrigation Project (SCIP) to produce sufficient food for the nourishment of as many Nigerians as possible, and ensure the continued viability of the Lake Chad.

In regards to both issues, perhaps it would be profitable to draw the attention of the federal government, the CBDA and other stakeholders, to the thought-provoking study by Marina Bertoncin and Andrea Pase, of the University of Padova, Italy, published in their seminal work “Interpreting mega-development projects as territorial traps: The case of irrigation schemes on the shores of Lake Chad (Borno State, Nigeria)” as meriting a close consideration.

Another important scientific paper worthy of note is “Interbasin Water Transfer to Recharge Lake Chad for Peace, Security and Economic Development in the Lake Chad Region”, by the former Executive Secretary of the LCBC, Engineer Sanusi Imram, and Professor S. Mustafa, which should be given the attention that it certainly deserves.

In order to fulfill its mandates and remain useful in future, the CBDA will need to be turned inside out, so to speak, by way of reorienting it towards a new outlook that would essentially entail two primary tasks. These are to secure adequate water supply for the entire areas to be cultivated under the first three phases of the South Chad Irrigation Project (SCIP) which covers around 72,000 hectares of irrigated land.

However, for reasons that are self-evident but hardly acknowledged, only between 7,000 to 8,000 hectares are under cultivation at the best of times because of lack of electricity power and acute shortage of water. Power is critical to pump water but in the absence of water itself, the need for power is vitiated. Therefore, both problems must be resolved in tandem in order to make the SCIP come true.

The continued reliance on diesel generators is no longer sustainable due to the high cost of the product, which has risen from around 30 kobo per litre in the 1970s, to more than N1000 per litre. The current power configuration of the CBDA which is about 35MW provided by five small capacity generators that are too costly to maintain and operate. It, however, requires not more than 5MW to start the power for pumping the water for irrigation along 39 kilometer length of canals in its areas of operation. This meagre power requirement can easily be supplied by capturing the abundant solar energy in the Chad Basin area.

But by far the most important requirement of the SCIP is water. Where this is scarce or altogether unobtainable, the purposes for the existence of the CBDA are altogether made irrelevant. It is for this and several other reasons that we have been advocating the recharging of the Lake Chad from any viable sources in order to prevent its extinction and increase its water content to meet the needs of the expanding human population in the entire basin.

It is in this light that the attention of the responsible agencies of the federal government is drawn to the outcomes of the International Conference on Lake Chad organised by UNESCO, the Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC) and the Federal Ministry of Water Resources in Abuja, in 2018.

It is about time that the key recommendations of the plenary and syndicate sessions of the conference are revisited with a view to their implementation by the federal government. Without Nigeria taking such a bold step, no other country in the vicinity of Lake Chad has the capacity to mobilise both the internal and external resources that are needed to resuscitate the lake.

Nigeria is therefore the principal and most important agent in this exercise and as such, we must live up to this expectation. When all is said and done, the most critical requirement is the supply of water from other sources to recharge the Lake’s volume to prevent it from totally drying up.

The proposals currently on the drawing board are to draw water from the Ubangi-Chari Rivers through an inter-basin water transfer scheme. This plan is already favoured by the LCBC as indicated from the decisions of the 2018 International Conference. However, other alternatives exist that could be equally feasible and perhaps less complicated and more cost-efficient. Two programmes that I am privileged to be privy to have been developed by the intrepidity of some Nigerian engineers and water experts that proposed to draw water from rivers inside Nigeria to recharge Lake Chad.

The first proposal was developed by the team of KETSWA Engineering & Project Management Ltd, under the direction of Engineer Hamid M. Al-Sharief, while the second plan was conceived by the engineering firm Geosciences & Aku Limited and Partners, led by Asriel Akusa George, both of which proposed a radical solution to the problem of Lake Chad through taking water from the River Benue. The merits and feasibility of these proposals will form the next and final instalment in our presentation of the case for rescuing Lake Chad.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.