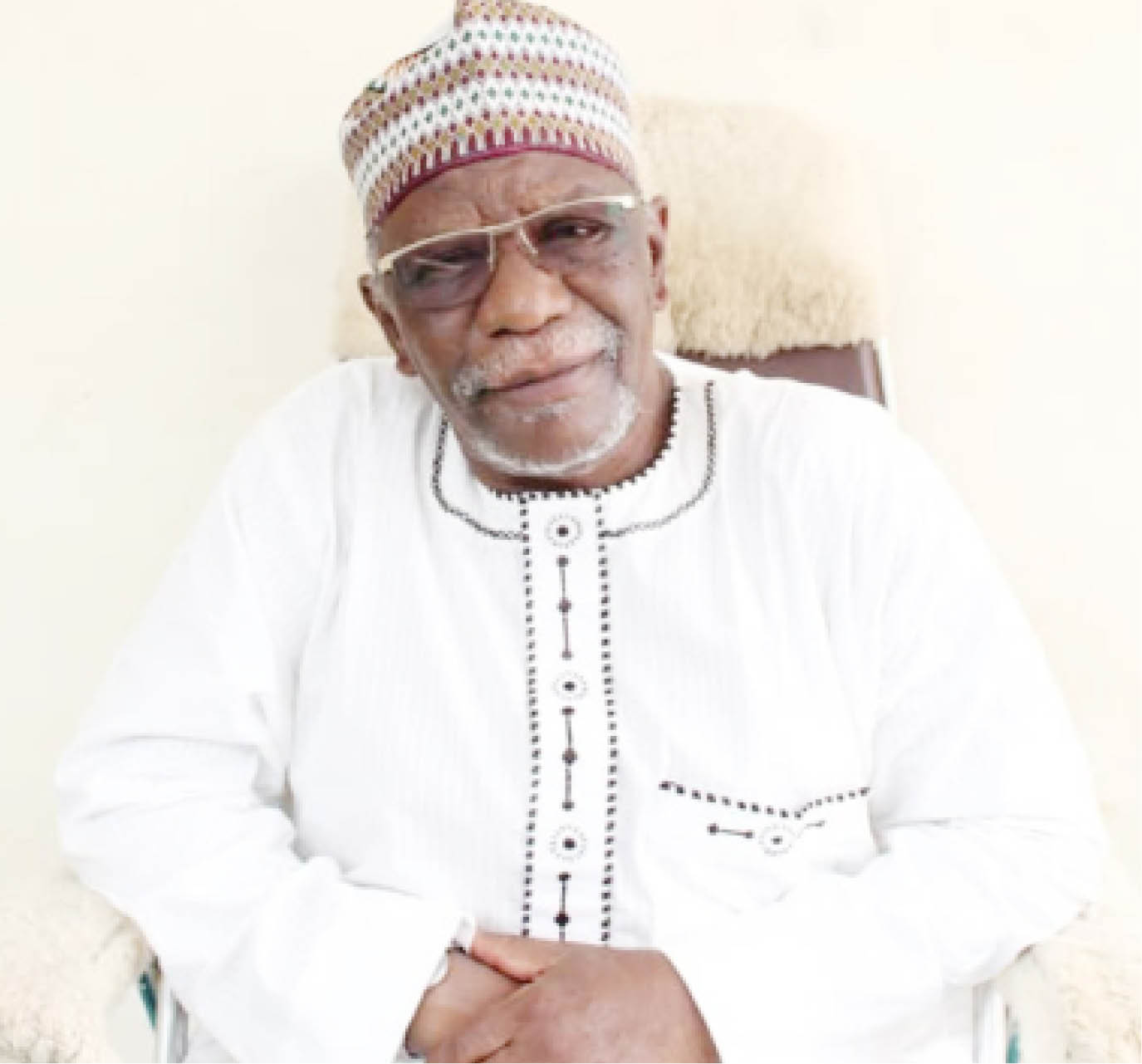

Professor Bello Ahmad Salim, OFR, a former registrar of the Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board (JAMB), turned 71, recently. In this interview, he spoke about intrigues during his days in the JAMB, as well as other issues.

How has life treated you generally?

I will say I belong to the blessed generation. We were schooled under mango trees, where we used stones and sticks to learn mathematics. We went to both Islamic and western schools, got home tired and sleepy, so there was no room for laziness.

- PHOTOS: Police occupy Lekki tollgate to prevent protesters from reassembling

- #OccupyLekkiTollGate: Drama As Officials Are Forced To Push Van Conveying Arrested Protesters

I remember that after three months, we were moved into the classroom and were made to sit on desks. We were taught how to handle a piece of paper and pencil. You didn’t start using ink until you got to class three. And you would make sure you put your pen into the ink well enough that some of it smeared on your hand so that you could rub it on your head for people to know you had started using it. That was like a reward for excellence for us.

We had to do well as teachers would report to our parents if we did wrong. And everyone in the locality could correct us because a child of the locality belonged to everyone.

From primary to secondary school, we were fed and given weekly allowance by the government. We were given journey allowance, some amount per mile to and from school. Junior boys were given 3pence, senior boys about 6pence, and some higher students in Form 5 or so were given 3shillings.

Regardless of our parents’ statuses, we were treated equally.

We were also made to learn hand craft or agriculture. People in my age group call ourselves the blessed generation because we enjoyed so much when we were growing up; things that our children don’t enjoy now. The parental and school care we received made us more mature than our chronological ages. They seem to have disappeared now.

And maybe because of our small number in my generation, we had jobs. None of us knew how to write an application letter; we were only taught that in secondary school. We didn’t need it; neither did we go for job interviews. In fact, by the time we graduated, the only problem we had was what job to pick.

After your first degree at the Ahmadu Bello University (ABU), Zaria, you went to the United States for further education at a time the US was considered inferior to the United Kingdom in terms of education; what informed your decision?

In 1960 there was a link between Ohio University in the US and Kano State. What is now known as Federal College of Education (FCE), Kano was built through that kind of link. We were the first set of the National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) scheme. I was sent to the West. Just at the end of the one-month orientation, which no one knew what it was about anyway, we received a radio message that my friend, Prof Ahmadu Bello and I were to report in the ABU at the instance of the vice chancellor, Professor Ishaya Audu.

Foreign members of staff in the department where we graduated (Nigerian Languages) were leaving and there was nobody with the training that my friend and I had, to run the department.

I was trained as a phonologist. I went to Ohio University after my national service at the instance of the ABU. We were appointed as assistant lecturers immediately after the NYSC and we were advised on the university to go for the particular training they wanted. I got a solid training in Ohio University. In fact, when I went for PhD at York in the UK, I didn’t have any hurdle.

Up till now, if you want quality education in America, there are those Ivy League colleges and some other top colleges, and if you want a third rate education, there are those county colleges. Ohio University, Athens, was a private university built in 1804, so the government will not spend money sending people to a third rate university. At Ohio, I was trained both in linguistics and teaching of English as a foreign language. For a number of years, I was one of the people actually conducting TOEFL in Kano centre for all those going to the US for postgraduate or first degree.

Why didn’t you return for your PhD in the US?

The same Ohio University granted me admission in speech and hearing, but my then head of department realised that if I had taken the admission and got a PhD in speech and hearing. I will be of no more use to the university (ABU). I would have had to end up in the hospital, helping people who had speech and hearing defects. So, to ensure I still go and qualify in theoretical linguistics and phonology, they chose another university for me because they wanted me to do what they trained me to do. That’s why I ended up going to the University of York, which is one of the feeder universities for Oxford University.

How did you settle in York despite the differences in settings between Ohio and York?

There was a difference in culture, Ohio was an open society. By the time I applied to York, they had a habit of granting people provisional admissions. I was made to attend classes with undergraduates, with people who were just going for their masters, and given assignments to test my competence. If you didn’t get your first degree from them, they make you go through that. The first time I took a class in theoretical phonology and I gave a talk on natural phonology, my supervisor called me and said my admission has now switched to provisional master of philosophy and I didn’t need to attend the class anymore. Others had to stay a whole year while I went straight to my research.

After a year, they reviewed my work before being granted a provisional PhD. Not to be too proud, I think I was the first foreigner to go to the University of York, complete everything within the three years and pass through each and every step without hurdles. God has been kind to me.

When you emerged JAMB registrar in 1996, what were the intrigues? What was the experience like?

Before I went to the JAMB I was appointed the chairman of the Kano State Agency for Mass Education. I was there for five years. I was also an SA to the secretary of Police Affairs. Two people I respected were sent to tell me to report to the Police Affairs in Abuja as the appointment was already signed. I wasn’t consulted.

It was the same thing for the JAMB. Somebody told me he saw our names in the Villa being submitted for something, but I didn’t pay much attention to it.

I went to see my mother one Sunday evening and we were watching television when I saw myself among others. That was how I found out that I was appointed the registrar of the JAMB. I had been with JAMB from inception, so I knew its inner workings, but I never expected the appointment.

When it was announced, there was a lot of terrible press, asking, ‘What does a professor of ‘Hausa’ know about the JAMB? I remember that one of the staff members called me Alhaji when I resumed in Lagos and I was angry. I drew the attention of his superior to it, that I had been a professor since 1990. I made them realise that my qualifications got me the position.

Because of the negative press, we set a record – Dr Mohammed S. Abdulrahman and I. We knew each other since ABU days when he was in charge of the School of Basic Studies. When it was announced that I was taking over from him, he asked the government to allow the two of us work together for a whole month, prior to the handover. We went to some of the key offices of the JAMB in Nigeria.

We were dealing with those printing our security documents in Britain. He introduced me and showed me all the intricacies. For a whole month, he would be in the registrar’s office and I would be somewhere nearby and he would suggest the files that should be brought for my attention.

Senator Prof Jibril Aminu, a former minister of education once said in the Senate, “Bello, you and Abdulrahman impress me and I wish heads of government parastatals would act like you so that this country would move forward.”

So, for the 10 years I spent in the JAMB, I never did anything without consulting Mr Angulu (pioneer registrar) or Dr Abdulrahman; they also advised me when they perceived something was about to go wrong.

I had a terrible experience with the press in the first examination we conducted. It was then that I initiated the idea of exam monitoring. I also initiated the opening of offices in all states. The first office I opened was Ekiti. I also started the juggling of question papers, having types A, B C, D. I first tried it in 1997. The following year we juggled even the answers too to curb malpractice. One person’s question 5 was another person’s question 25, and question 5’s right answer would be C, while the same answer of the same question in question 25 would be A, for example.

We also introduced the catchment area and admission quota during my time, such that the locals, as well as people across the country explored and enjoyed education. It was supposed to give equal chance to all citizens who wanted to learn anywhere in Nigeria.

Your 10 years as JAMB registrar cut across a period of transition for the country from military regime to a democratic dispensation. What was the transition period for you?

At the initial stage, I served without a board. So, actually, whoever was the minister of education would be the chairman of our board. And because of the absence of a board, we had to come up with a contration, an expanded management, where we asked for representatives from the Federal Ministry of Education, Office of the Head of the Federal Civil Service, Office of the Secretary to the Government of the Federation, just so that we would have a semblance of a board with others other than just JAMB management staff making the decisions.

Boards were later appointed in 1999, after the transition. The boards can be very helpful. In fact, there are two members of my first board with whom I have become brothers.

Initially, it was not easy because the board would come with certain expectations, and you who were running a parastatal were supposed to follow certain guidelines. And those guidelines were also given to the boards. If you got a very good board chairman you were lucky because he would keep other members in line to know that they were there to help you come up with policies to help the organisation and not to get contracts. I was lucky. Some of my colleagues were not so lucky because they had running battles with their boards because they were only interested in contracts and the board chairman would be asking for Prado jeeps.

I am not saying I did not face certain challenges where a resolution from above would be brought to me to accept. When I started online registration in the JAMB, it was our idea but some people wanted to chip in on it. They convinced people above me that they should be allowed to run it, generate the revenue and give JAMB something out of it. They even lied that it was going to be a World Bank-assisted programme and we won’t need to spend our money, but all they needed for us was to sign. They wanted the minister to force me to sign. They wanted to play the devil’s advocate between me and the minister until the minister later realised that I was only protecting the ministerial seat and that those people were nothing but briefcase contractors and what they wanted for us to do was to sign something that I would have been very rich by now. But by the time I am dead, none of the money would follow me. They wanted me to get on board and promised that for every form sold I was going to have a percentage. I said, ‘Ok, is that percentage going to follow me to my grave?’ The problem with these people took me up to the presence of Mr President. Thank God he listened to us and took over JAMB for that time and changed ministers. That’s former President Obasanjo. Things were that bad. To give Obasanjo credit, he listened. He didn’t take a report at face value.

At that time, I remember I was even cancelling certain centres because when I discovered too much malpractices and warned people and they didn’t listen, the following year I could cancel a whole town. And the president backed me. A lot of what I did had the backing of my superiors. That’s why I said I was lucky. And some of my staff encouraged me. I even started getting housing estates for JAMB staff. I am not blowing my own horns but to emphasise how lucky I was.

You once suggested the introduction of mobile courts for examination malpractice. Are you satisfied with the level of compliance to this?

I am not. Human beings, not only Nigerians, have very funny characters. We pronounce holiness only in our mouths, unless we see somebody beside us with a big stick.

Exam malpractice is a universal disease. Thank God Nigeria is way behind. Some of the so-called advanced countries are in the premier division in exam malpractice. And the more technology they devise to run the exam, the more technology the cheats also devise. There have been cheating cases, even in TOEFL, Oxford University and public exams in China, India, US and UK.

Our problem here is that even when we say we have arrested people for doing XYZ, that is the end of the story. When I was in the JAMB, we financed the drafting of what we called exams malpractice law. We the examination bodies had to come together. Admittedly, we were so angry at the time that we made our case to the Federal Ministry of Justice, that exam malpractice was very heinous and it should attract a very stiff penalty because if someone cheated to become a medical doctor, you know the hazards. We told them that if someone was found guilty, he or she should be jailed for seven years.

I know the JAMB is doing its best now, but I wish it would be backed. If they arrest somebody, let the public see that something has been done, even if it is 10 lashes in public.

I remember that during my time, I would hear of something and report to Alagbon Close that something was going on in Ife, but before the police left Lagos to get there, the perpetrators were alerted and they would leave town. It can be very frustrating. That was the only frustration I had, but I enjoyed my years in the JAMB.

I thank God that I did my first term and Allah made it possible that four months before the end of the term, the president directed that I should continue. I was to finish my first term in October, 2001, but by July, 2001, Mr President had already approved my second term because the minister recommended it.

Sometimes over a million students register for JAMB each year, yet only a small fraction get admitted into higher institutions. What is the way forward?

The government has just approved more private universities. In Britain, everybody wanted to get a university degree and nobody wanted to be seen with a polytechnic diploma; so all those West and South London polytechnics and the likes were turned into universities. The situation is similar here, even from the primary school level. People want university education, so give them. After all, government is for the people. All these polytechnics and colleges of education were set up to cater for middle level requirements, but apparently, nobody wants to be lower or middle class again. So I will suggest that these polytechnics and federal colleges of education be made degree-awarding institutions. At the end of the day, the market will determine which kind of degree they value.

There was a time that if you had an ABU degree it was a passport and you didn’t even face an interview for employment. Later, it became the turn of the Bayero University, Kano (BUK). When I was in the JAMB, I knew a lot of organisations that were just employing some students simply because they had BUK certificates.

Our population and development needs indicate that the higher institutions we have are far less than what we require. If we had up to 600 it would not be too much. But the quality they come out with will be determined in the labour market.

I recall that when we finished primary school, we took a regional common entrance and top students are shortlisted for interview for certain designated government colleges. In the then Western Region, none was bigger than Kings College and Queens College. Then there was Federal Government College, Ughelli in the East, and in the North, there were government colleges in Keffi, Zaria and Kaduna, and for the girls in Ilorin.

It didn’t matter who your parents were, if you were a top student you were shortlisted for interview in these top colleges. At that time, a student paid fees based on the assessment of his parents’ income. One of my classmates at the Government College, Keffi was the son of the then prime minister, Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa and he was paying the highest school fees, alongside some of the children of the ministers. They were paying 36pounds per year.

We were not in Keffi because we were children of so and so. Before we got there, our names were posted on the assembly wall, along with our province, native authority, primary school attended, scores in English, Mathematics, and the interview. And this list would remain on the wall until the next set comes in. It was very transparent. The training we received was also topnotch, and that is why we are proud of the late Umar Musa Yar’adua; he also went to Keffi.

I brought this history because you asked the way forward. Let the movement and training of the youth be as open as it used to be. A lot of us enjoyed privileges, not because our parents were emirs or prominent people. Maybe we were lucky we had parents who paid attention to our development. And regardless of which village one came from, they were all given equal training and chance to succeed as the children of the rich.

Unfortunately, now we have a system where there is a big gap between the haves and the have-nots; and these other youths are annoyed with us and our youths because they see our youths enjoying everything, and as far as they are concerned, they are denied access through no fault of theirs.

Even though the country’s population has grown, that former system can still be brought back, where there would be a level-playing ground right from primary school. We can do it; otherwise you people have the right to say we have betrayed the trust given to us because we enjoyed free school meals. We were fed at the university and our cloths were washed by washmen and paid for by the government. Admittedly, we were a small number, but some semblance of the care and concern, especially for the children of the have-nots can be restored.

So, I beg the government to open up more universities. Let those who can afford it pay for the private ones. They should set up foundations to pay for children of the have-nots. I know a lot of people that are doing this quietly, but let us have more people.

On a more personal note, how blessed are you through your family?

This is really on a personal level, but I don’t know how many people of this generation can try this. One, my biggest blessing is that Allah has allowed me to still have my mother to look up to. She has been the pillar. My father died the year I graduated from the higher institution, 1973. He knew I graduated, but he never saw my convocation. He encouraged me, and that’s why I encourage my children. I don’t play around anything to do with education. Even in those days when people in Kano did not know where Keffi was, my father allowed me to go to Keffi for my secondary education, which was then in Benue Province. That time, if you left Kano today you would get to Keffi tomorrow. He also allowed my younger sister, two years later, to go to Ilorin in 1966 for her secondary education.

My uncles started teaching me and my sister right from home, and because of that, when we got to school, we were brighter than others. I am blessed by parents and relatives.

Also, as a Muslim, I am allowed to have up to four wives, if I think I can be fair, but before I got married, I never knew I would have more than one wife. I never liked the idea at all. But I ended up having three wives. All of them have postgraduate qualifications.

I remember that one of my female ministers of state for education referred to them (my wives) as my corporate support services. She came to my house in Abuja once and said she only remembered one house in Maiduguri, and then, my house where the housewives were interacting more like sisters and with their husband as elder brother.

I am also glad that today I have given my children enough leeway that they now meet and propose and sometimes decide to tell me their decisions on even things that concern me. I am blessed with children and wives, and I have no regret on any of them.

I and my wives are truly friends. Love does not lead to long lasting marriage, but friendship. You have to be friends for the love to grow, then you can trust and respect each other.

I am blessed with a family whose tradition is education and part of traditional titleholders. My mother’s family has the title of the Sarkin Dawaki Mai Tuta, one of the kingmakers in Kano. My paternal grandfather was the Ma’ajin Kano from 1936 to 1953 at the time when Ma’aji was the real power; when he was the minister of finance, budget and emergency relief. Everything finance of the Native Authority was controlled by the Ma’aji and you didn’t put someone who is illiterate in charge of these things.

I am proud of this lineage. Maybe that set me up on a course. Up to now, if you check around 8:30pm, I will be with my mother, unless something happens. If I am in Kano, I am with her every day. Anyone whose parents live long and he has the opportunity to live long with them but misses the chance to go to heaven has himself to blame because it is a favour from God. You take care of your parents and have an assurance of God’s favour.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.