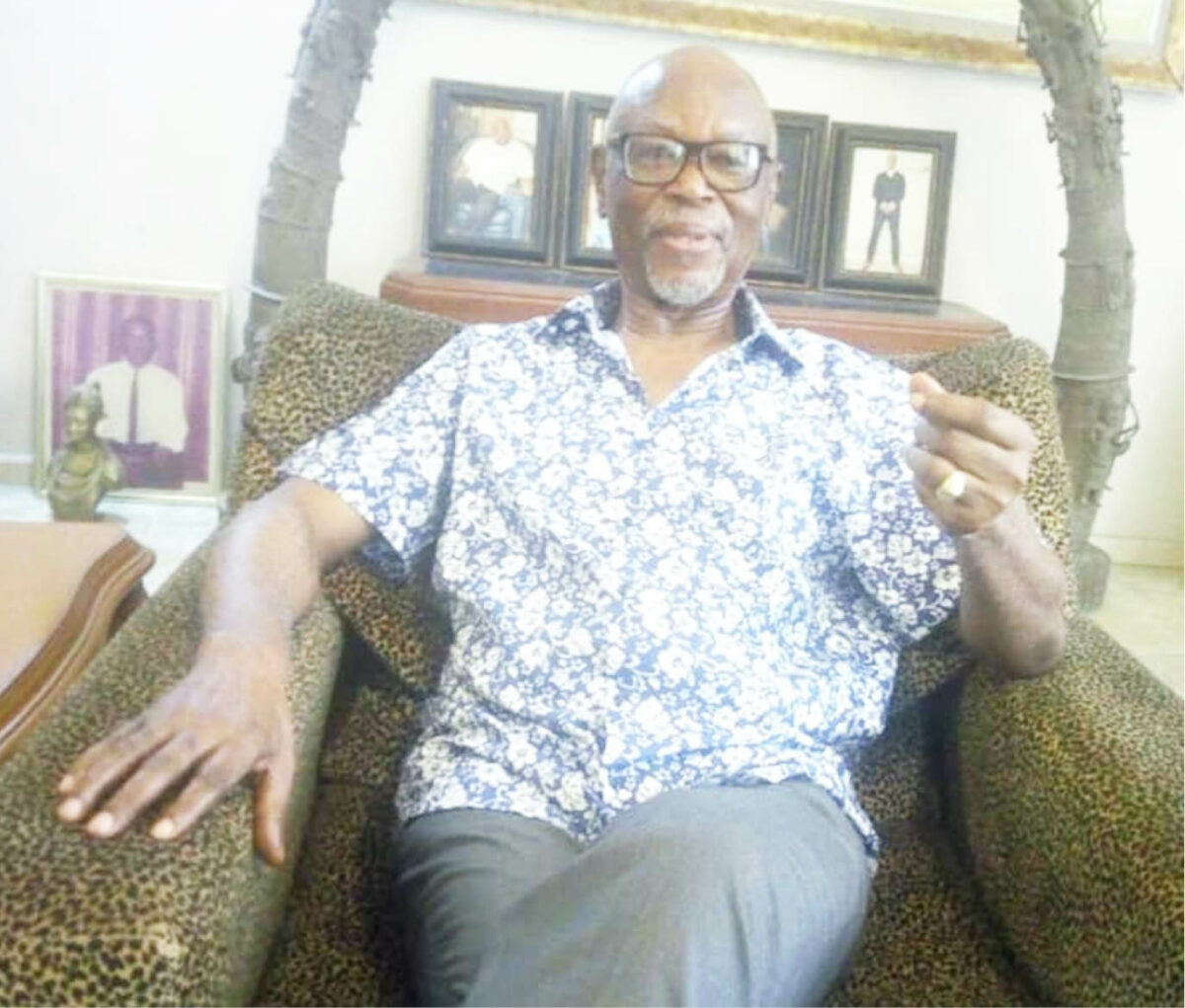

Chief John Odigie Oyegun, 81, is a former federal permanent secretary, governor of Edo State and national chairman of the All Progressives Congress (APC). In this interview, he spoke on his early life, how he defied all odds to rise in his career as a civil servant, how he escaped from the country during the clampdown on members of the National Democratic Coalition (NADECO) after the annulment of the June 12 presidential election, his political life, among other issues.

How would you describe your early stage in life?

I am not sure it was particularly eventful. I was born in Warri, in the present day Delta State. Up to 1950, I was in Standard III when my father was transferred to Benin. We came to Benin in 1951 and I attended Holy Cross Catholic Primary School in 1953. I started secondary school from Standard V.

Some of us were allowed to take the common entrance examination from Standard V. Three of us passed the exam and went to secondary school without a Standard Six certificate.

Early years were good. I remember being in nursery school in Warri at an early stage, but things changed when our house got burnt. Our standard of living and every other thing collapsed.

My father worked in the judiciary. He was a middle class citizen. We lived fairly well, but after the fire incident, everything nosedived and we started wearing khaki jumpers.

The second ugly incident was when the Nigerian farmers and the commercial bank my father invested in collapsed. It affected my father because he was planning to go abroad to be a lawyer and had saved for it. He was an interpreter in the court. When that happened, it affected his plan to go and read Law, as well as the family’s standard of living. Aside these two unfortunate incidents, we had a lovely childhood.

How did the house get burnt?

No one knew. It could have been an open lighter. It couldn’t have been electricity because we are talking about the late 1930s and early 1940s.

What dramatic event happened in your primary school days that you can recall?

It was just the usual childish prank at school. The only thing that was a bit out of place was that we were playing with camfo, and somehow I got one into my nose and we couldn’t get it out. That created a lot of panic before the teacher took me to the hospital, where they managed to get it out.

I don’t know what we were doing with camfo in school, and we didn’t know how it came to the school. Maybe some students put it in their bags, apparently to prevent rodents and other insects from getting in.

In Benin we had a school farm, and every year, during the harvest period, each pupil took a slice of the harvest home as an evidence of what they had done. It was very good and it coincided with our feast day in the school, where part of the harvest was cooked for both teachers and pupils. We all ate and had a good time.

What was your father’s reaction to the camfo incident?

My father didn’t get to know about it because I didn’t tell him. The teacher had taken me to the hospital and they got it out. Would you go and report yourself and get trashed for being careless?

Tell us about your university days

It was fairly straightforward. In those days, everything depended on your performance in your secondary school certificate. The school authorities had the ability to get your result directly. I tried to go to Kings College. I did the examination in Onitsha, but it didn’t work out, so I applied for admission into the Nigeria School of Arts, Science and Technology in Ibadan, which was basically a preparatory ground for those who wanted to study engineering, land survey, among others courses. It was an intermediate institution preparing people for professional courses. They just took some of us who wanted to do A-level or one of the professional courses. I did my A-level there and transited to the University College, Ibadan.

How would you describe your primary and secondary education, compared to what obtains now?

I can’t compare it because I am not in school now, I can only talk on hearsay. But then, it was very good, let me talk personally. I don’t know where I got the gift of reading books from. I read virtually every book available. I spent hours of my free time in the library in Benin, reading books. It was a lucky habit I developed that turned out to be part of my personal development and attitude to life. Before I left secondary school, I had read lots of books authored by Shakespeare and lots of other books. I knew the speech of Mac Anthony off heart before I finished elementary school. I was that gifted.

How was university life?

Beautiful; we were very lucky. It was not as congested as they are now. I had a room to myself at A-level, but in my first year in the university, I shared a room with a Ghanaian medical student. Thereafter, I had a room to myself. We were spoilt in those days in school. We had people who did our laundry. At the beginning, we were served when we went for meals; you would sit down and be served. At the tail end of my school, it became a cafeteria, and we demonstrated over that. So it was good.

After that demonstration what happened?

The school authorities stood their ground, of course and the cafeteria system was established. Looking back, it was so ridiculous. Given where we were coming from, sitting down and being served whatever you liked, it was a radical change. You know that changes are not easily accepted, especially when they infringe on your absolutely misplaced dignity.

Did cultism exist in your days?

Such things never existed. We were more into intellectual pursuit. I belonged to the Embassy Club. I also belonged to the Inner Circle, a group that developed your personality positively. It was a very tight group of friends whose main objective was to behave like gentlemen at all times. Those days in the Inner Circle, it was good.

How was your job hunting?

In those days, we were lucky. You could still move from job to job. And the normal thing was civil service. Job hunters came to the school before you finished. The first choice for graduating students was always the public service. It was just like entering the University of Ibadan in those days. You must have three papers. Some people who made it successfully in life couldn’t even make three papers. It was those that couldn’t get into the University of Ibadan that struggled to go abroad to study. Also, in job placement, it was those that couldn’t get public service that joined the private sector because it wasn’t as developed as it is now.

So how did it go?

I applied to the public service commission. I went for the interview and was sent to the Inland Revenue Department. I reported there, but I didn’t like it. I immediately wrote to the Public Service Commission, stating that it was not the kind of job I wanted. They wrote back, offering me a permanent employment on a three-month probation. I wrote to thank them and informed them that that was not the career plan I had in mind.

My boss was not too pleased with me, but it eventually worked out for me because after a short while, the commission wrote to me to come for a second interview. After the interview, I got deployed to the newly established Ministry of Economic Development. I think that was one of the best things that ever happened in my life.

But let me go back a bit. At the college I was a member of the Nigeria Youth Movement, led by Otegbeye. The form I filled was to become a career diplomat. I wanted to work in the Ministry of External Affairs. I suspected that they had the record of my activities in the Nigeria Youth Movement.

Nigeria was a colonial country and we were anti-colonialism. Communism was just becoming prominent and the group was part of those who processed scholarship for those who gladly accepted to be trained in Russia. So I believe they had some information about me and deliberately wanted (that is my interpretation) to keep me away from the administrative and diplomatic service.

I have a feeling that they wanted me to be in economic development. Their thought was, ‘Let him go there and be talking theory.’ It turned out to be the most fortunate deployment in my career. At that point, I had a good fortune of interacting with the best minds in this country; people like Ayinda, Imebo, Philip Asiodu, Professor Aboyade, among others, who did a lot for this country.

What did you read in the university?

Economics and Political Science.

During your career in the civil service, how did you rise to become a super federal permanent secretary?

I don’t know whether there was anything like super permanent secretary, but I became aware that my views were highly respected. Going back, I read a lot during my youthful days – story books, history, and any book I came across.

When I applied to the university I was given a scholarship to read History. I went to the History class, and at the third time, it was as if I was wasting time there because there was nothing they were talking that I didn’t seem to know about, so I asked myself how I could spend three years going through this? I could see a red flag. I said this won’t work at all, and I had to change.

I walked to the Department of Economics and told the head of the department that I came to read History, but I was not enjoying it. I asked if I could join the Economics class.

He looked at me and asked for my certificate. He also asked if I had done Economics before. I said no, but added that I could catch up and that I would start reading elementary books on it.

After accessing my certificate and the rest, he offered me admission and I was very glad. That was how I got to read Economics.

Going back to your question, I was just doing my work normally and I didn’t know, perhaps, my bosses noticed the quality of my work, so I gained a bit of respect. One day, I was in my office and reading a book on transportation economy and my boss, who was a deputy permanent secretary, Imel Ebong, walked in and said, “So you are interested in transportation economy; that is good, there is a course going on in Washington, I think it was being sponsored by World Bank, I will nominate you for that course.’’ That was how I went into transportation economy.

I went to Washington for three months, came back and eventually grew to become the head of utilities, which included all modes of transportation, communication, roads, among others. It was quite a heavy responsibility.

So I did my work to the best of my ability and it pleased those who supervised me. I became a permanent secretary when I least expected it because I was a level 15 officer. I read a report and part of the recommendation was that a level 15 officer should be in the pool of those to be considered for permanent secretary when it was considered.

Normally, you have to be a level 16 officer and above before being considered for the position of permanent secretary. I wasn’t even the head of department. One day, I was in a meeting of the Nigerian Port Authority when a friend looked through the door and beckoned on me. I took permission to meet him and he asked if I had heard what was happening? I asked what and he thought I was pretending. He asked, “You mean you don’t know that you are being considered for permanent secretary?’’

I told him not to joke with me and went back to the meeting. When I got home, my neighbour who worked in the Cabinet Office came to me and said I was going to be made a permanent secretary.

Unfortunately, it created some issues in the public service system because I was nominated over my boss. I was shocked too.

Eventually, it was sorted out as they replaced me with my boss. It was during the regime of General Murtala Muhammed.

What happened thereafter?

I was promoted to level 16 as compensation. I was pulled out of transportation to the Ministry of Education. I was told to head the ministry for three months because the permanent secretary, Mr Liman Ciroma was long overdue to leave.

I was very young and the ministry had lots of old people who had principals, including the principal of the King’s College, where I applied. It was a very fantastic experience. At the end, we worked well together. After a while, I was pulled out again to the Ministry of Works and Housing as secretary for finance and administration. I spent three months there.

After three months, I was again redeployed to the Cabinet Ministry, which is today the Office of the Secretary to the Government. I headed the economic department of the office. I did my job well and I knew that things were going well for me because occasionally, when they had technical issues I was called upon and made to head the technical office.

For almost a year, I was appointed acting permanent secretary, something that had never happened in the service. At the end of one year I became full permanent secretary.

Maybe that was what gave rise to me being a super permanent secretary. The real super permanent secretaries were Philip Asiodu, Ayida and Ahmed Joda. I had a great acceptability of them because when they held meetings they insisted I must be there. In one particular occasion we had to go to the then Yugoslavia for an alliance with a construction company to come and work in Nigeria and I was a day late for the meeting. As I arrived they gave me the draft agreement that had been negotiated. I read through and I told them that some things had to change. So they had to reconvene for another meeting. That showed that they had respect for my views. So if you want to know how I became super permanent secretary, I don’t think I was qualified. I listened to super permanent secretaries with respect when they spoke because they were really the best.

Were you married before you were appointed permanent secretary?

I got married in my first year in the civil service. I married my permanent secretary’s secretary.

I had to see the permanent secretary on and off, so I couldn’t help but notice her. She was beautiful and very well behaved, thorough and efficient. I was still an adventurer, but when I got to her, I said, ‘yes this is what I want.’ We lived in the axis, and occasionally, I offered her a lift. So one thing led to another and we are still together after 55 years.

Tell us about your NADECO days.

It was a unique period. We had a set of upcoming politicians who were qualified, dedicated and strongly believed in the country. In the process, good-minded persons naturally decided to resist the then military head of state, Ibrahim Babangida, who annulled the election of Moshood Abiola without a reasonable cause. For me, it became evident that we had a problem and that problem was the military, who had become competitors for power. And unless we took the opportunity to let them know that their place was in the barracks and to defend the country and not in governance, we would continue to have interchange between them and civilians in governance, and that may bring permanent instability and the country would never move forward. That was how I found myself in the NADECO.

How did you escape the military clampdown on the group?

Edo State was one of the places that protested violently for the total abolition of the system, and I was blamed for it. This was totally far from the reality because I was in Lagos at the time it happened. Chief Tony Anenih was attacked and Augustus Aikhomo’s house was razed and they declared me wanted. I had to stay underground in Lagos, doing what we could, and raising funds. I and Olusegun Osoba collaborated in keeping the movement going. And since I was declared wanted, I said I must not be captured and sent to prison because I knew they would finish me. I had to consult my friends in the military who said they would leave me alone if I made a statement denouncing the activities of the NADECO. I said I couldn’t do that and they advised that I should get out of the country. So I found my way out of the country and joined my colleagues in London.

How was it over there?

It was fantastic because Chief Anthony Enahoro, Sen Ahmed Tinubu and few others joined us.

Did leaving the country affect you and your interest?

Oh, that reminds me that I have truly made sacrifices for this country, from which I have not recovered. I have a factory here in Benin that was producing furniture; the military raided it twice, and thereafter, workers were afraid to go to work and the place collapsed, so my economic base was destroyed. I had to sell a few properties to enable me survive for a while. It has been a heavy price I paid for the love of the country, and I am glad I was able to pay.

You became the governor of Edo State, how was politics then?

There is no comparison. I got a few vehicles and was able to traverse the whole of the then Bendel State without police escort. We went through the state without any incident and accident. It is now a totally different picture.

It was a beautiful experience. I enjoyed campaigning than being governor; it gives you the opportunity to know the people as they truly are. You would see the beauty of humans and culture.

Sometimes I came back with a substantial amount of money, which I asked all those who accompanied me to share. One particular incident struck me, which I will never forget in my lifetime. It happened in one village where one woman donated her last money for my campaign. That gesture touched me. So, when I became governor, the first challenge was what I could do that would affect every household in the state. In my inaugural address, I chose education, urban transportation and health because it would affect every household.

Education and hospital services were free. Fairly minor cases were treated free of charge, but you paid for complicated cases. Those who put me in the office and paid taxes should also share in it, and thereafter, what remained would be used for infrastructure and other developmental projects.

Your family has managed to remain off the public radar although you are popular. How have you managed that?

Well, that is basically my lifestyle, and I thank God that I am not greedy about physical assets and money; that is what brings problem. If I have billions in the bank, maybe that temptation would be there. Greed has never been my portion, so my children and my wife are walking their way through in life like every other person. I thought that all I needed to do was to show that honesty is the best thing that can set you to the target of what you want to be, not stealing and illegal accumulation of wealth. Basically, that is my lifestyle and I have been able to show good example, that you can get to the top being straightforward, honest but hardworking.

Where do you think we got it wrong as a country?

I think it is a rot that manifested itself but we did not pay attention. Secondly, I think we have been very unlucky in leadership at the federal level. Unfortunately, we promised change but we inherited a bad economy. The misfortune multiplied during the last four years. Everything that can go wrong has gone wrong economically.

We have not been able to move as fast and deep as we need to, but I think the president got his hand on the right thing, which is corruption. Corruption has become very entrenched and destructive in the country. Nigeria is not the only corrupt country in the world, but our own type of corruption is the one that eats out the capital base of the country itself. Being an honest person now is like living in disgrace because people keep demanding from you. Every day I must get five texts from people asking for money to pay some bills, as if I had the money to do all the things they are demanding from me. They have assumed that having been in these positions I have accumulated money like every other person. If they can’t get from me they will say the man is stingy and selfish. And I am just managing myself; but I don’t have any apology for that because that is who I am.

Do you believe in restructuring?

Restructuring is good for the country and nobody is going to lose. I don’t understand why people are against it. I commissioned a team when I was party chairman to do something on it. It was headed by the governor of Kaduna State, Nasir el-Rufai. It was a beautiful report, which we considered within the party at the working committee caucus level, and at the National Executive Committee level.

The report was well accepted and the president was very happy over it. We were commissioned to implement as a party and it was then I knew that all was not going well because I thought it was to be a governmental thing. We had already drafted laws that would be pushed to the National Assembly for passage. It was tailored in a way that it would have been a gradual process, giving states enough time to be strong enough to handle their new additional responsibilities. And the whole issue of resource control was sorted out. States were to control their resources and the Federal Government was to control deep sea oil. So why it hasn’t made progress, I don’t know, because it is something that will benefit every part of the country.

The APC believes in true federalism; the report is there, it is just awaiting implementation.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.