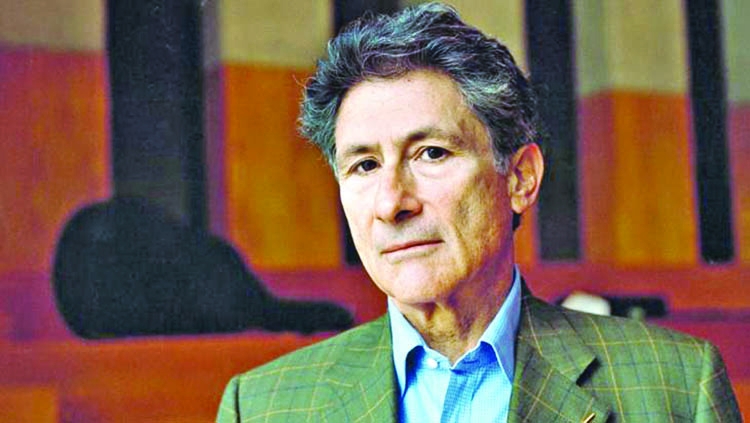

As Israel continues the bombardment of largely civilian targets in Gaza, nine days into the war between it and the Palestinian resistance movement, Hamas, and as Western media continue to relate events according to their own jaundiced politics, I could not but recall the writings of one Palestinian intellectual, Edward Wadie Said who died 20 years ago, in 2003.

I first learned about Edward Said around 2010 during a postgraduate class on “Identity and Cultural Difference”, that is, principally media and other cultural representations of difference, in which Said’s most well-known book, Orientalism, was a compulsory reading. I read the book, and my eyes opened for the first time, perhaps never to close again about how mediated texts of all kinds represent people, places and issues, locally or internationally.

In Orientalism, first published in 1978, Said makes three arguments, two of which are, in my view, original, while the other builds on the works of others before him. Following up on the post-structuralist ideas of French theorists like Jacques Derrida and Michael Foucault, Said agrees that there is always a connection between language, or discourse, knowledge and power. How we speak about a thing, a person, a people, or a place, or even an issue, is not always necessarily the objective reality of those things about which we speak. Rather, how we speak about others and indeed what we say about them may reflect more the power differential between us and them than the objective reality of who they are.

For Said, all that the West says about the East, or the Orient, particularly the Middle East, in different kinds of texts, be it the political speeches of Western leaders, or the dispatches of diplomats working in far flung areas of the East, or the supposedly “scientific” and historical writings of Western researchers, or yet the reports of journalists and foreign correspondents in the Middle East, and the cinematic or literary texts of film Western makers in Hollywood and literary giants like Conrad and the like, all of these western modes of representation of the Middle East, tend only to reinforce one another in their biases.

- Liberia’s election: ECOWAS warns against premature declarations of victory

- Gunmen kill 3 in Benue community

These different kinds of texts and modes of representing the Middle East reinforce one another because, Said argues, they are all based on a supposedly inherent distinction or difference between the East and the West. The West is orderly and rational; the East, by contrast, is chaotic and emotional. The West is democratic and free, whereas the East is despotic and unfree. In this sense, Western identity itself is established, Said says, not by saying what it is but by differentiating it from what it is not, namely, the Other, the non-West.

It is this manner of speaking and writing about the East, that is, permanently in terms of the binary opposition between the West and the non-West, which Said insists can be found throughout the works of Western politicians, diplomats, academics, journalists, poets, and other categories of “creative” writers and performers, that he calls Orientalism.

Finally, Said argues that Orientalism is not only a mode of speech or representation of the East, particularly the Middle East, by the West just for its own sake. Rather, he says, Orientalism does political work. Orientalism is, for Said, nothing other than an imperial agent in its own right. Western cultural representation of the Other, for Said, furthers the political and military domination of the West over the Middle East. Labelling people as despotic, violent, fanatic, terrorist or as irrational and irritable helps to justify your appropriation and exploitation of their resources, or indeed, justifies your own violence against them.

Said wrote primarily about how power relations between the West and the East are represented in language and other forms of cultural production, but the points he makes apply beyond just the Orientals. It is the same way, for example, that Americans spoke about African slaves in the so-called New World. In order to justify the total domination of the slaves, and to explain away the social and physical violence meted out to the slaves daily, the slave masters needed to speak about the slaves as being inferior, as being childish and incapable of learning, except, of course, through the whips of the slave master.

Centuries later, it was also in much the same way that the Europeans spoke of African colonies right here at home: as being morally and spiritually corrupt, inept, uncivilized and so on. All of these ways of speaking about Africa and Africans, whether in the writings of literary writers like Conrad, or in the works of colonial adventurers and administrators like Lugard, Smuts and Rhodes, were intended to justify and further the political domination of Africa by Europeans, and by implication, to explain away, the expropriation of African land and resources.

Indeed, writing a few years before Said in 1975, the Nigerian sociologist, Claude Ake, reached much the same conclusion about what he calls “the rhetoric of domination” employed by Europeans to advance their colonial adventurism in Africa. Similarly, the Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe, working from a literary-critical perspective much the same as Said’s, but unlike Ake’s, in an article appropriately titled “An Image of Africa”, says much the same thing about European representation of Africa as being imperialist in both design and effect.

Orientalism then, is a concept for understanding the discursive power relationships between the West and the Rest, not just the East. But more specific to our purposes today, Said continues the arguments outlined in Orientalism in his 1980 book, Covering Islam. Needless to say, Said was a Christian, as were his parents and grandparents before him, who was in fact named after Prince Edward, the Prince of Wales at the time of Said’s birth in 1935, the same Prince Edward who as King, would later abdicate the British throne in favour of the woman he loved.

Still, Said’s clear-eyed analysis of so-called “international media”, that is, Western media, coverage of Islam and Muslims is, to the best of my knowledge, unmatched.

Continuing his arguments from Orientalism, Said delivers a powerful theory of the media as an “invisible screen” which filters objective reality for large audiences by blacking out what it doesn’t want people to know about others as much as about themselves. Said argues that the primary tendency of Western media is to distort the reality of Islam and Muslims, and indeed the Muslim World.

Using the Iranian hostage crises to illustrate, he concludes in Covering Islam, as in Orientalism, that the distortion of the image of Islam and Muslims by the Western media is primarily to further Western political domination and expropriation of the Muslim World and its resources, including, in the case of Palestinian Muslims, the appropriation of their land for, and on behalf of Israel. And it is here that Said reaches from the 1970s and 1980s to the present day.

Anyone who has followed CNN and the New York Times, perhaps the two most distinguished media in all of the world, not to mention hundreds of other influential, if less illustrious, Western media, would feel ashamed at the unabashed, and crude one-sided representations of the ongoing war between Israel and Hamas. All effort has been made to individualise and humanise the suffering and loss on the Israeli side, but not for the Palestinians whose lands Israel appropriated through some of the worst terror campaigns in human history.

But then, of course, it is Orientalism at work yet again, now as ever.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.