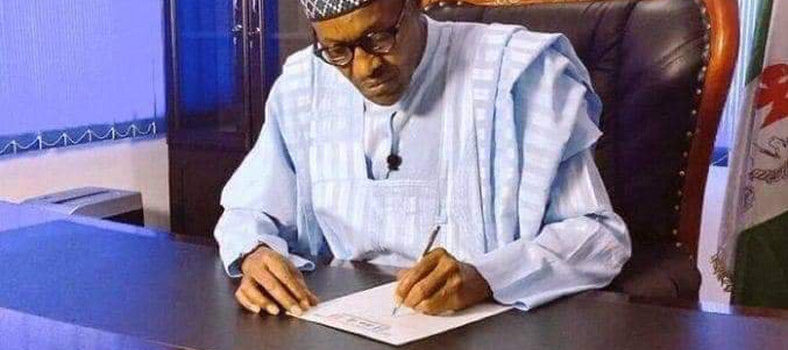

A Nigerian president is, by definition, a politician. In his letter to the National Assembly detailing his reasons for not assenting to the Electoral Act Amendment Bill 2021, however, President Muhammadu Buhari spoke not just as a president but also as a political scientist. In fact, reading the letter, I thought the president is giving our professors of political science a run for their money.

In the five-page letter, Buhari advanced seven arguments against the provision in the bill for direct primaries, his sole reason for dissenting a bill that contains other equally significant provisions. The president said that direct primaries will entail unbearable costs for all stakeholders—INEC, political parties, candidates; that these costs will further fuel corruption and monetisation of our electoral system; that direct primaries will increase security challenges and limit the freedom of choice for parties and candidates; and finally, that direct primaries will increase litigations of election outcomes since they are not free of manipulation and malpractices either.

These are all very cogent arguments supported by extant political science, even if one disagrees with some or all of them. There is no theory or issue in political science with which everyone agrees. The requirement for serious ideas or arguments in political science is not perfection or consensus, but reason, logic and evidence. The president’s letter scores high in all of these. And, unlike the error-strewn report of a judicial panel led by a retired judge only a few weeks ago, the president wrote in crisp, clear and concise language.

Surveying the uproar that has poured forth on the pages of newspapers, on social media posts and comments, and on radio and television programmes, however, you might think the president was actually involved in some egregious scandal. He wasn’t. He was merely doing his job by withholding assent to a bill, something any president would do from time to time, given the push and pull politics that go with policy-making and legislation in a democracy.

Where necessary, withholding assent to a bill is part of a president’s job, regardless of how others receive it. And only the president has the power and prerogative to decide what ‘necessary’ means in the preceding sentence. But to better understand that letter and the president’s professorial thinking in this instance, we need first to explain the form and substance of the hysterical reactions that followed the president’s action.

Legislative politics is painstaking, not straightforward. Unfortunately, our media and civil society organisations are generally unfamiliar with and have rather straightjacket and simplistic assumptions about the politics of policy and legislation. People genuinely expect a president to give assent to a bill merely because they favour its provisions, and are, therefore, shocked to see that has not happened. In this sense, the uproar that has followed Buhari’s refusal to ‘sign the bill’ is by itself an indictment of the National Assembly. If our lawmakers had been in the serious business of proposing and making groundbreaking legislations, the back-and-forth politics involved would be familiar, and people would not cry foul merely because a president has a different view about the place of direct primaries in our electoral system.

More broadly, Nigerians have an ‘auto-pilot’ understanding of democratic politics. We expect democracy to work swiftly and smoothly without any hitches like a train driving itself. But that is fantasy, not reality. Democratic politics is an aggregation of often very different and conflicting interests, and no one gets all of what they want all of the time: not the president, not the legislature, and certainly not the citizens or those who speak on their behalf. You win some, and lose some. The president has won this time, but it is not necessarily a permanent victory, because it is not the end of the process. It does mean that the process starts all over again. So what?

Anyone familiar with the legislative politics of abortion, gun control, healthcare, election financing, appropriations and taxes, and many more, between Congress and the White House in the United States, for example, would have seen something similar play out a thousand times. The Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) signed by former President Obama in 2010, without support from a single Republican lawmaker, had been in Congress in one form or another since the days of President Truman in the late 1940s. It was killed and reborn several times by previous presidents and congresses, and no one knows if it could still survive the next decade.

That is precisely the nature of legislative politics in a democracy. And democratic politics, in general, is inherently about gains and reversals for a wide array of public and private interests ranged against one another; neither a playfield of the saintly, nor a self-piloted train that moves in only one direction. It will be better for everyone if we in Nigeria learn to understand and accept this. So contrary to the dominant rhetoric of the past few days, the president’s refusal to sign the bill does not make him ‘bad’, neither does it mean that the National Assembly and Nigerians who support the bill are ‘good’. It just means that they differ on the same issue and the one person who has the constitutional power to decide one way or another has done so.

Those who favour the bill still have the power to turn things around under this president or the next. In my view, the direction of action should lean towards this, not holier than thou rattle. I have argued in favour of direct primaries and other provisions of this bill on these same pages not long ago. I still stand by my position. But I am not convinced mass hysteria and noise would achieve them, now or at any time. This leads us to perhaps the most important aspect of this issue.

When Lincoln defined democracy as the government of the people by the people and for the people, he was not making an easy statement to be repeated by idle commentators. He meant that democracy is a job; a huge burden for the citizens. And one way to translate his definition is that democracy is a form of government which requires active citizenship. This is arguably the most important missing link in Nigerian democracy today.

Our citizens are almost completely removed from the democratic process at almost all levels, particularly in the period in between elections. We have constituencies but no constituents. We have political parties but no partisans in the serious sense of the term. We have a large number of angry armchair critics, but no organised and systematic mechanisms for channeling opinions and views to influence politics and policy in certain directions. Even the civil society organisations, the labour unions and the media are just as removed from the people as the government they criticise.

Regardless of what the parties may claim, I doubt very much if any political party in Nigeria has up to 200,000 card-carrying members in total, in a country of more than 80 million registered voters. And for every lawmaker in the National Assembly, 80 per cent of the citizens they ‘represent’ probably don’t even know the lawmaker’s name, let alone what they stand for politically. This is worse for the lawmakers in state assemblies. So inactive citizenship of the many leaves the stage for the few citizens for whom partisanship is a business. The politicians then buy those ones out and leave the rest of us to grumble on the side, or rather to pay the price of inaction. This is the real problem, and it must change.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.