Gas flaring, which is the burning of natural gas that is associated with crude oil when pumped up from the ground, has remained a serious problem to the environment, thus, a nightmare to many communities where such is practiced.

Documented reports showed that gas flaring has impoverished the communities where it is practiced, with attendant environmental, economic and health challenges.

However, the negative effects of gas flaring have been linked to contamination of both surface and ground water, contamination of soil, increased deforestation, as well as the economic loss and environmental degradation.

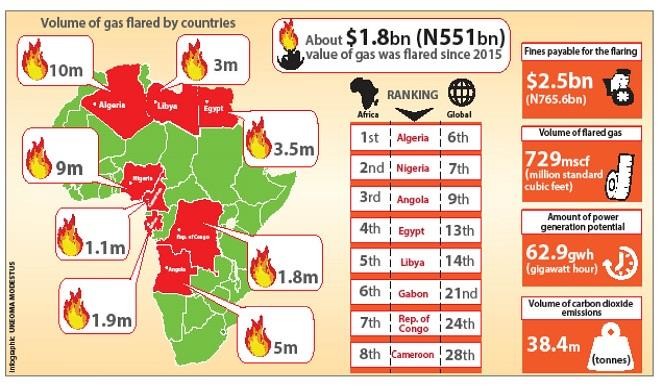

Oil and gas firms operating in the Niger Delta region have flared gas valued at N551.2 billion ($1.8bn) in the past two years.

The firms, as result, face a fine of about N765.6bn ($2.5bn) for a flared gas volume of 729 million standard cubic feet (mscuf) from 2015, statistics from the country’s gas flaring tracker has shown.

The gas being flared is said to have a power generation potential of 62,988 gigawatts hour (ghw) and over 38.4 million tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions, the tracker created in 2014 by the Federal Ministry of Environment and National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency (NOSDRA), revealed.

Satellite images provided by the tracker located 222 of such incidents happening around 65 onshore oil wells scattered across Edo, Delta, Bayelsa, Imo, Akwa Ibom and Rivers states.

At the World Bank-led Global Gas Flaring Reduction (GGFR) partnership (GGFR) seminar held in Nigeria in March, the Federal Government stated that it was committed to ending routine gas flaring, and unlocking its gas potential.

The World Bank Group (WBG) in its report then, said about eight billion cubic meters of gas is flared in Nigeria annually while citing satellite data. It said the country, the seventh largest gas flarer in the world, still has 75 million persons that lack access to electricity.

Further analysis of the data shows that Nigeria reduced gas flaring by about 2 billion cubic meters from 2012 to 2015. Global gas flaring records from 1996 to 2015 show that while oil production increased by 31 per cent to 90,000 barrels per day, gas flaring was only reduced by 11 per cent to 150bn cubic meters yearly.

Oil production reached its peak in 2015 and gas flaring was at its highest globally in 1996 when it was over 160bn cubic meters annually.

A three-year new ranking scale between 2013 and 2015 published by the GGFR team also showed the top 30 gas flaring countries with Russia topping the list with over 20m cubic meters. Vietnam was the least with a gas flare record of about 1m cubic meters.

Nigeria, at the seventh position, flares about 9m cubic meters. There are seven African countries in the scale after Nigeria. Algeria occupied sixth position with 10m cubic meters; Angola is ninth with 5m cubic meter record, and Egypt 13th having a record of 3.5m cubic meters.

Others are, Libya occupying the 14th position with about 3m cubic meters; Gabon 21st with 1.9m cubic meter record; Republic of Congo 24th with 1.8m cubic meters, and Cameroon 28th position with about 1.1m cubic meter gas flare record.

Expressing the Federal Government’s desire to do more, the Minister of State, Petroleum Resources, Dr Ibe Kachikwu, at the seminar presented a roadmap to end routine gas flaring by 2020; about 10 years ahead of the target in the global ‘Zero Routine Flaring by 2030’ initiative which Nigeria endorsed in 2016.

In a WBG statement on the seminar, Kachikwu’s Senior Technical Adviser, Gbite Adeniji, said: “This massive amount of gas flared annually in Nigeria is a waste of energy that our country just cannot afford. Now is the time to step up our efforts and what is needed are innovative, bold approaches to flare reduction.”

The GGFR Programme Manager, Bjorn Hamso, said: “Through seminars like this we are getting a better sense of what needs to be done to end routine gas flaring in Nigeria.”

Reactions trail timeline to end routine gas flaring

The Chief Executive of Connected Development (CODE), Hamzat Lawal, said ending routine gas flaring by 2020 as stated by the minister was a political and ambitious statement that cannot be achievable in reality.

Lawal said for Nigeria to stop flaring gas, “it means we have to put stiff penalty to oil and gas industries and the key players in the industries that are currently flaring the gas.”

He said: “As we know today, our policy on gas flaring and the penalty, the industry players prefer to flare gas than to save the gas and channel it to industrial or household usage. For them it is cheaper to pay the millions of dollars or billions of naira fines than to work around technology to channel these gases.”

He said the data and statistics from government is credible, but that there is need to do an independent data gathering and analysis of how much gas is being flared and how it is affecting the economy of the nation

“Economically, the gas we are flaring today can actually be channeled to households and institutions to curb our silent energy crisis, where over 50 per cent of households are not connected to the national grid,” the Lawal said.

He noted that Nigeria cannot stop flaring in 2020 because it is not ambitious in making the PIB bill see the light of the day, he said the bill was one of those political instruments that would give that gateway to stop flaring gas in the country.

He, however, said it was more important that there was more transparent and accountable governance structure in the oil and gas industry beyond just making political statement.

Lawal said, “We need to see clear commitment and stronger policy that will ensure stronger institutions.

“The institutions on ground need to be strengthened and funded adequately to be able to meet their deliverables because if they fail many people will go scot-free and keep devastating our environment,” he added.

The National President of Environmental Management Association of Nigeria (EMAN), Emmanuel Ating, said achieving zero gas flaring by 2020 could only be feasible if the oil producing companies retooled some of the things they used for production and if there was a working legislation on ground as well.

The government, according to him has to be clear on the flare out – whether it is a complete flare out or a partial flare out – adding that if it is a complete flare out, how does it intend to fund it because there would be an injection or gas recovery programme.

He noted that the Federal Government was flaring the gas because it had the highest percentage, 60 per cent, in the gas sector agreement.

“The NNPC has to take a cursory look; they have to retrospect to see what they have done to put their head in order so that they can achieve a zero flare out in 2020. The prospect of them succeeding depends on how sincere and transparent NNPC operates,” he said.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.