The flurry of reactions that trailed the alleged ceding of Nigeria’s sovereignty in certain loan agreements with China last week must’ve been interpreted by those in the know as amusing, misinformed or, more accurately, typical sensationalism. Nigeria was sold a long time ago.

So much has changed since Nigeria, intoxicated by the oil boom and pan-Africanism of the 1970s, boasted that it had come of age and threatened Western powers meddling with its interests as Africa’s self-appointed Big Brother. Nigeria packed a punch when the Portuguese armed forces invaded Guinea in 1970, bellowed loud when Western powers were reluctant to sanction apartheid South Africa, and brought its power to bear when the U.S. backed a rebel group to take control in Angola.

This initial gra-gra didn’t end well. The period itself is remembered as one of impressive rhetoric but grandstanding nonetheless. The effort of the Gowon-led government to unplug the country from foreign economic influence inspired the Nigerianization policy of 1972, facilitating the takeover of foreign-owned companies. In effect, this policy saw the transfer of competently-run businesses to the Nigerian rulers and the pan-ethnic elite, who steadily ran them aground. Subsequent juntas furthered this praxis and indigenised large-scale corruption that would go on to stall routine, even if doomed, reforms.

This anti-Western posturing, which reached its zenith in the Murtala-Obasanjo regime, was not unprovoked. The Nigerian civil war had taught the elite a hard lesson, having counted as a betrayal the initial hesitation of the British government to provide military support to the Federal Military Government, the declared neutrality of the U.S., and France’s supplies of arms to the separatist Biafra. At a point, the Nigerian war effort was powered by Soviet bloc arms.

Parlaying the post-war oil boom into charting an independent international course was logical but, in retrospect, not thought through. A lack of administrative competence in local industry, and a growing rent-dependent elite, made disaster inevitable when oil prices fell to under $14 in 1986. The Soviet bloc was undergoing Gorbachev and in no position to throw a lifeline, and so Nigeria, prodigal son of international politics, crawled back to the old “devil.”

The deal was provision of loans and aid in exchange for, well, sovereignty, which was enforced as Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs). Those solutions from the IMF and the World Bank saw Nigeria tele-guided into a worse hardship, the economy tanked and the middleclass was destroyed. The people lost their country. Their country had lost its sovereignty in the major way it matters—in economic terms.

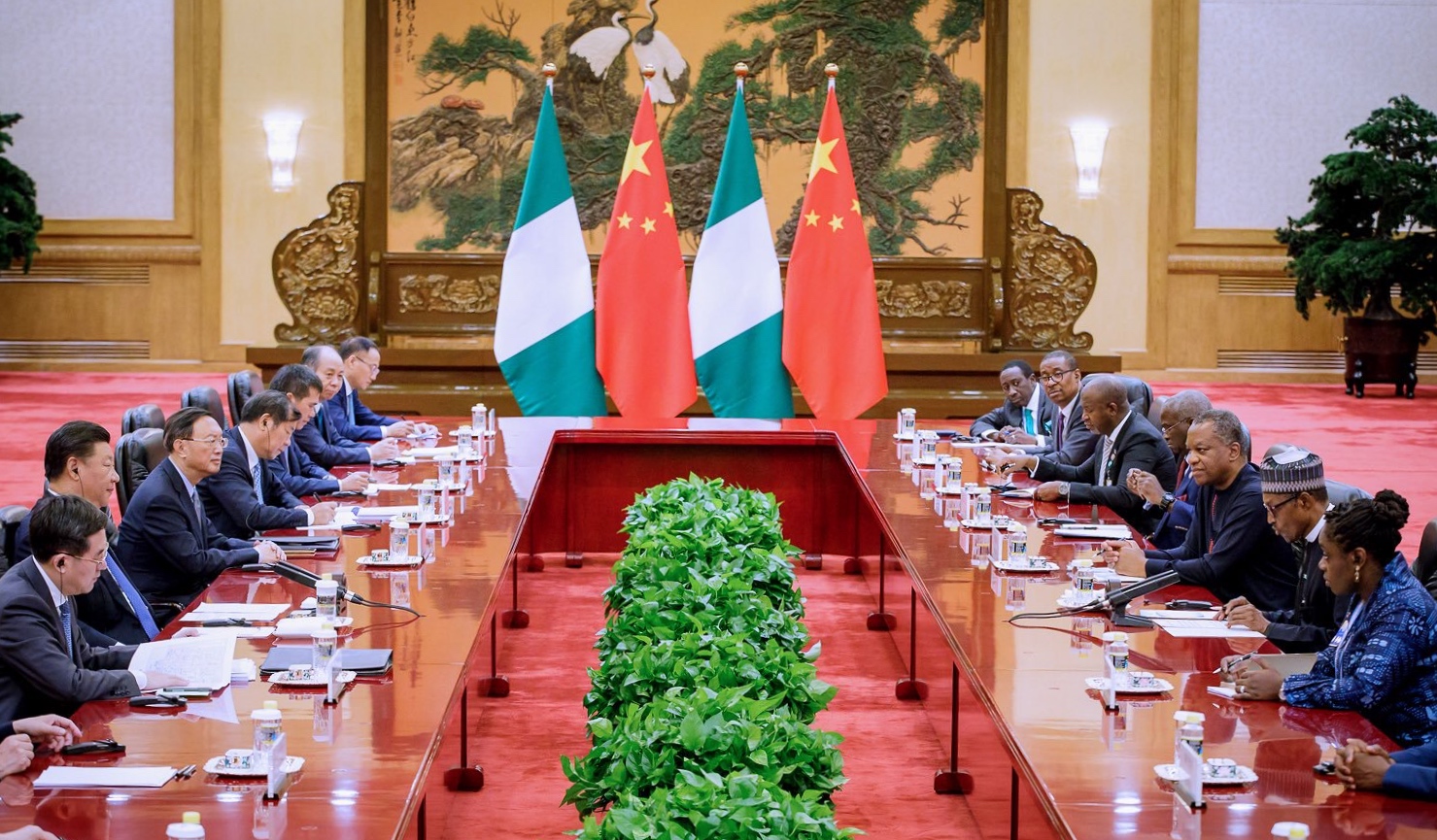

The trending representation of our elites as vendors of “sovereignty” in Beijing is a reminder of that pact with the West. Although Nigerians are right to pay attention to the documents being signed on their behalf, the nature of the present Chinese loans isn’t one that authorises the takeover of Nigeria or some equally wild variation of this. It simply means that Nigeria won’t enjoy sovereign immunity as guaranteed under international law if sued for defaulting on the loan repayments and during any arbitration proceedings around the breach of the terms of the loans.

Nigeria and China are willing partners who found each other based on mutual interest. Beijing had suffered humiliations, including economic blockades, from the West, and they weaponised that history to foster South-South cooperation. When the West imposed sanctions on Nigeria during the Abacha regime, the threat was instantly understood by the ruling elite and a response was devised—Abuja’s “Look East” strategy to counterbalance the West.

But, is the East a safer option for Nigeria? China defies the stereotype around which it’s wrapped. It’s been portrayed as a colonizing power masquerading as a development partner but these narratives are driven by Western alarmists or civil society with little knowledge of statecraft or realpolitik. Nigeria isn’t a victim in its partnership with China.

China is Nigeria’s top import origin, amounting to $9.6 billion (2017 data), well ahead of the U.S. with $2.04 billion. Nigeria is also China’s second highest FDIs destination in Africa. Even though there are downsides for Nigeria in the partnership, including de-industrialisation, persistent trade imbalance, and escalating over-dependence on imports from China, Nigerian elites aren’t unaware of the options before them.

Beijing must never be confused with Santa Claus, though. They have their objectives, but colonisation isn’t one of them. They need energy-rich countries to safeguard their expanding economy, and partner states to help them survive the politics of international institutions and the West. That contentious clause in our loan agreements, which may see the takeover of Nigerian state property in the event of a loan default, will never be enforced. Why? Beyond the fact that China is the master of optics in projecting soft power and knows that an aggressive response to default will trigger animosity, the Chinese are playing a larger strategic game. They understand the gain of masquerading as the benign partner in outplaying the U.S., as done when the bullying Donald Trump came for the WHO.

Two years ago, there was a viral report that China seized an asset in Zambia, and Sinophobic alarmists cited it furiously to emphasize the danger of China’s expanding loans. The story was false, but continues to be shared. That’s more indicative of the poverty of the Nigerian intellectual space than the real international strategic bromance between the two countries.

Nigerians, and in fact Africans, must sit back and rethink the way forward. We can’t outsource development to foreign powers without mortgaging an aspect of us. We must recognize the capture of industries by an incompetent elite and undo this in favour of a true private sector that will unleash latent value. Our appeal in Beijing is partly proportional to the certainty of our commodity, but evolving technology points to an expiry date of fossil fuels. Abuja’s salesmen must stare harder into the future of this dependency. But how can we do this when corruption is the lingua franca of our bureaucracy?

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.