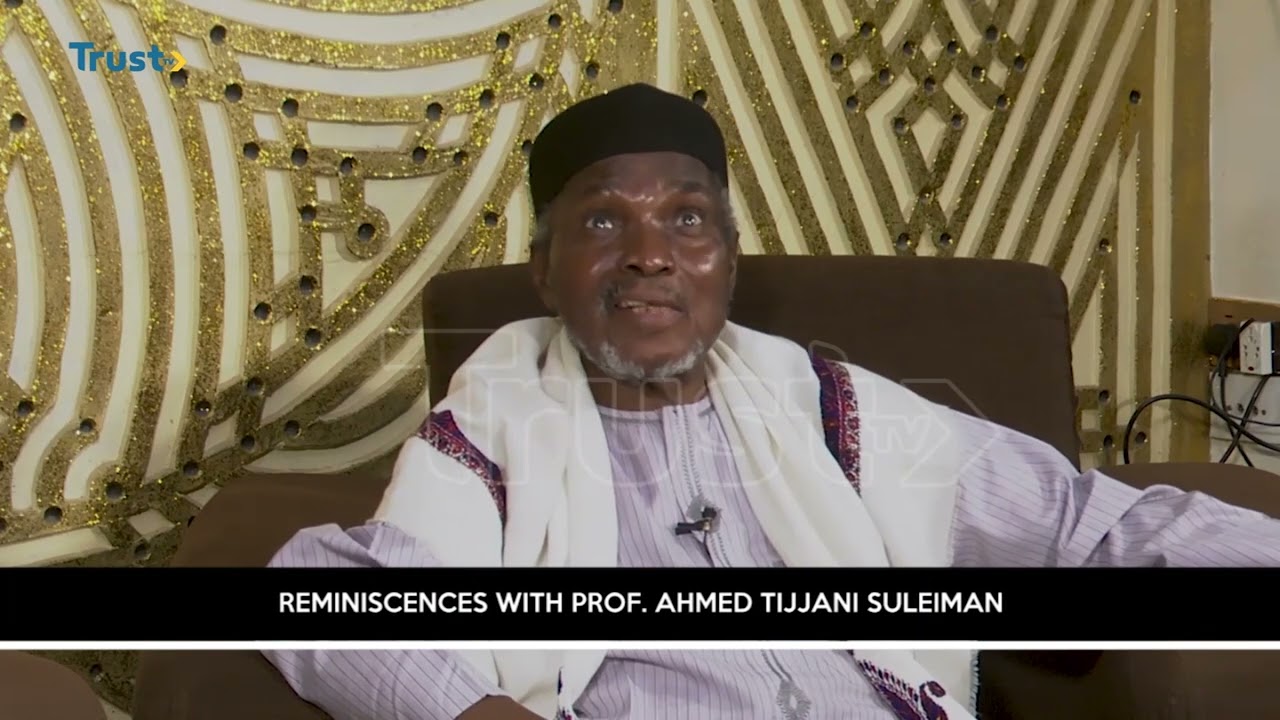

Prof. Ahmed Tijjani Suleiman, Emeritus Professor of Energy Engineering, was trained at Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, where he taught for a few years. He moved to many places, including the University of Sokoto, where he rose to become the Deputy Vice Chancellor. He subsequently became the Vice Chancellor, Federal University of Technology, Yola and for a brief period, Acting Vice Chancellor, University of Abuja. He has also served in the public sector in his state, Jigawa, as commissioner, and was two-time president of the Solar Energy Society of Nigeria.

Let me start by asking you about the early days in Ringim, Jigawa State.

I was born in 1945; on September 28th. I remained there for the normal six, or seven years before you are circumcised and then sent to Quranic school outside town. So, I can say my earliest years in Ringim lasted between 1945 to 1950-51. The tradition then, most of our parents didn’t like ‘boko’; didn’t like this modern education. They saw it as anti-Islam, and so on and so forth.

All my seniors were always taken outside town for Quranic schooling when they reached the age that they could be taken to primary school.

So they were taken out to (avoid) going to primary school?

- No public funds withheld, Kyari counters NEITI’s claim

- Ibadan runway excursion: NCAA suspends airline permit as NSIB begins probe

To escape going to primary school, and I was no exception. Fortunately for me, I was taken not too far away from home. I was taken to Malama Taura, which was just about 13km or so away.

Unfortunately, before all these tricks, I may call them, to get me out of town so that I didn’t go to school, the headmaster had already enrolled me; my name was already on the list of those who should join the primary school in the year 1952-53. The pressure was so much on my dad that they had to send my eldest brother to bring me back to Ringim.

Where was the pressure coming from?

The pressure was from the authorities. They were threatening that for that year, anybody who refused to get his child into school would be taken to Kano, to face the Emir of Kano and tell him why not. My father was ready to do that.

To face the emir?

To face anybody, rather than allow me to go to primary school. But my mother had a second thought. She looked at all my seniors who were taken away and hidden somewhere and there was never any threat on my father to be taken somewhere. Then she said I should not be the one that would take him to that level.

She begged my dad to allow me; to follow the instructions of the local authorities that I should join primary school. And that’s how I found myself in January 1953 as a pupil in what we used to call Junior Primary School, Ringim.

So, after the normal four years of primary school then, there was the Senior Primary School.

We are on the eastern side. This time around, six of us from Ringim, from the same junior primary school, went to Gwarzo on the western side of Kano, to do our senior primary school.

You didn’t want to go beyond the senior primary school, yourself?

No, I didn’t really. In fact, it’s not the school that bothered me, it’s the distance. I didn’t want to even go to Gwarzo.

So, when the letters came, the headmaster called me to say that he was going to congratulate me. I said for what sir? He said you have been selected to go to Government College, Zaria.

I felt as if somebody had struck me. I said, “Zaria? Zaria is a long distance from here.” He said, “Well, fortunately, or unfortunately, you were the only one from this school who has been selected to go there”.

The other two that passed were going to Kano Provincial Secondary School, which is now called Rumfa College. I begged him to do anything, he said no.

So you went to Zaria?

In 1958, when I went back to Ringim for the holidays, they said in January I should report to Government College Zaria, which I did.

The family was comfortable, there was no difficulty?

No, I think they are getting used to my situation. It happened that I had a senior cousin who was married to somebody in Zaria at that time. So they thought, when I went to Zaria and was able to trace her I would not be lonely.

So everybody agreed, after all, what is it? And the comforting thing is that at that time, you know, our railways were working very well, so the stress of travelling to Zaria was not there because we were going to go by train all the way through.

And I found myself in Government College Zaria, and I discovered that there were six of us from Kano province then.

The whole province?

The whole province, because it covered the whole of northern Nigeria, so to have six from one province was not a small feat.

Do you remember the others at that time?

Oh yes, obviously some of them are now dead. The living ones now, are three out of the six. The first to die was one Ibrahim Kazaure, then Ibrahim Mukhtar died later on; much later on, after graduating from US.

The ones that are living now, myself, then there is Dr Maitama Bichi, who was a permanent secretary in Kano State, and then there is Mustapha Umar.

That was how we found ourselves in Zaria and things went on normally. Somehow I was adjusting, to say, if it is good, oh God, make me accept it properly.

Because up to the time I went to Zaria, actually, modern education was not in my mind at all. Whenever we were on leave, I was very happy because I could go to the Quranic school at night and so on and so forth.

And then I discovered that those colleagues who were never in primary school, who have been full-time Quranic scholars, I would come and surpass them. So I thought that I should be in that line.

In the last year of our stay at Government College Zaria, there was another examination before the WAEC, what they called examination for going to higher school certificate. It’s meant for the whole of West Africa. I was selected to take that exam for whatever reason and I did.

How many of you were from the school?

From Government College Zaria, I think I was the only one that was asked to take the exam. And I didn’t disappoint them because by the time the whole thing came back, they said, I passed and passed very well.

Then the next thing was where to go because there were very few places where they were doing higher school certificate then, that was 1963, and we were to join them in 1964.

Whereas my colleagues would be entering secondary school five, I would go and join HSC, what we used to call lower six. And the story was that I was to go to Lagos!

And which is the big one?

And that was the biggest one, because I’ve never bothered to find out where Lagos was. I know it’s very far away. They said it was at the coast.

So I said, what have I done? What have I done to deserve this catapulting; from here you catapult me to there, and then from there to another.

My interest then was either to go to the Nigerian Defence Academy (NDA) – 1964, the first set of cadets – or to another school in Zaria, the School of Agriculture, because I came from a farming family and farming is in my blood.

Either soldier or farmer?

Yes, either a soldier or a farmer. But the school authorities in Zaria – the principal, everybody – said, no, no, no, I could not do that; that it was not everybody that got selected to go to King’s College, Lagos, so I could not be an exception.

So, luckily again, the railways were functioning properly, and I was not going to be under the stress of road transportation. We were to go by rail. I ventured. I was alone from Barewa College, maybe I would meet some others from northern Nigeria who could speak Hausa or whatever.

I took the chance and joined the train and found myself in Lagos somehow. And while in Lagos, I discovered that there were a few others. There were two from Government College, Keffi, you know they were the twin colleges of northern Nigeria; Government College, Zaria, and Government College, Keffi.

And then there were two from Katsina province and two also from Borno province. In the long run, I discovered that I was not alone. I had people with whom we could chat, and who had common interests.

But how was the experience of being a ‘gambari’ in Lagos, did you find it difficult?

It was a terrible experience because the majority of those who were in our class, were in the lower six – there were two arms, lower six arts and lower six science, and I was in science. So you will find that those who actually did their WAEC in KC looked down on all of us.

You were the provincials?

Whether you came from Kano or from Enugu or from wherever, if you were not from Lagos or some of the nearby towns like Ibadan, you were regarded as a foreigner, I guess.

So they started teasing us that some of us would soon leave; that it has been the practice, blah, blah, blah. If you do not make the grades required for those to stay in KC, you will go.

We kept quiet; sometimes I would lose my patience and start hitting back. I said, look, we should wait and see who would go and who would stay.

During that period, if you were not from the Lagos area, they would find a father for you in the government of the federation, which was in Lagos there.

And since my names have Suleiman, Sule, they assumed that I must be the son of Maitama Sule from Kano. That is why I was brought there.

Unfortunately for them, they have refused to understand that the administrators of King’s College were foreigners. At that time, the principal was still English.

And no amount of pressure would make them admit somebody who was, according to them, not qualified. But we kept on exchanging unpleasantries.

When the WAEC results came, they being in Lagos, were able to get their results much earlier and it was posted. And eventually, when our results came out, most of us from the so-called provinces did very well.

Division One?

Division One, virtually all of us, really. Those from Borno, from Keffi, from Katsina, they were all very comfortable.

What of the big northerners in Lagos, the Maitama Sules, were you able to meet them?

Not as such because, you know, King’s College had a culture of its own. You were not allowed to be roaming about just like that. What you were there to do, you tried to do it well.

Why did you decide to go to ABU for your university degree? Was it deliberate or just something that was only available to you?

It was not deliberate. In fact, it would have been one of the last options. Why? I was then beginning to enjoy a change of location!

Since I did my secondary school in Zaria, I wasn’t anticipating coming to Zaria again for my degree, the same thing with the University of Lagos then. Since I did my higher school in Lagos, I didn’t even bother to apply to the University of Lagos.

I applied to the University of Ibadan. I applied to the University of Nsukka then and since I was entitled to three options, I added ABU. I applied to the University of Ibadan to do mathematics. I applied to the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, to do civil engineering. And then I applied to ABU to do…

ABU was last?

ABU was last, to do mechanical engineering. I didn’t even know the differences between all the engineering, all I knew was that engineering needed physics and mathematics, which was where I got my pleasure.

So, you all know the history of Nigeria. In January 1966, there was a commotion.

There was a commotion?

A coup d’état. The government was thrown out and all sorts of atrocities happened.

So, the chances of going to Nsukka then became very slim because you know we normally entered the university then in September, or October. So, by September 1966, things changed completely in the country. So Nsukka was no longer an option.

And the Northern states government then because we were still under one government called the Northern States, decided that look, even my Ibadan was not an option.

It was safer to move to Zaria?

Luckily for me also, because of the long period between the end of the school year and the beginning of the university year, I was posted to Bauchi, to teach at what was then called Bauchi Teachers College.

And I was there, just a few days after they brought the corpse of Abubakar Tafawa Balewa for burial. That really made me feel seriously offended.

So, eventually, I found myself coming to ABU. It was my last option but became my first and only option.

And did you regret studying mechanical engineering, because, you said you didn’t know the differences between all those?

No, not at all, actually because, you know, once we finished with HSC then, you know, the degree was a three-year course then, you will find that the first year was for all the engineering students, whether you were doing electrical, mechanical, or civil, you do the same thing.

Then in the second year, you do a lot with electrical and a lot with civil also. So, virtually, it’s only in the very final year that you specialize in certain areas that are called mechanical.

But by the time I started, I discovered that actually mechanical engineering is the only engineering! All others are supposed to be appendices.

I think I will leave this debate to the engineers….

Well, it’s not a debate, I have said my own feelings. So, I became very interested in mechanical engineering. I have not forgotten my original intention of being a farmer. I was looking at mechanical engineering as a way to improve our farming processes.

Luckily for me, the year that I was graduating from ABU, there was a plan to start what was called an agricultural engineering programme. It was not a degree programme as such but to try and get people, both engineering and agriculture graduates, to be trained as agricultural engineers so that after some time, a full department of agricultural engineering can be established.

And without my knowledge, again, I seem to be a very lucky person, people just suggest that I should do that. So, after my graduation from ABU, they that I was going to be retained.

In ABU?

In ABU and not only that, I was to go to what they call the agricultural engineering section, which was then a section under agricultural economics of the Faculty of Agriculture. I said, okay, fine. I can’t say no to farming, so I went there. And all that is now history.

Because you didn’t pursue that, you went to do a PhD in Scotland?

Many things happened when I went to meet the person in charge of the agricultural engineering section, he was an American called Dr Schneider.

He was one of those sent by non-governmental organizations in the US for propaganda, probably. So, we did not see eye to eye.

His idea of agricultural engineering was so different from my own. So, we did not see eye to eye, really.

I got so fed up that I did what many people thought was not doable. I took my paper and wrote a letter to the Vice-Chancellor then, Professor Ishaya Audu. I said I was going.

You were going to resign?

Naturally. As expected, he called me and started hammering me in Hausa, he said, “How can you get this opportunity and you’re throwing it away?”

And I said, sir, I appreciate what you people have done for me, for recognizing I have the talent to become an agricultural engineer. But, unfortunately, the person you put in charge of that section now is incapable of nursing an engineering department.

Then he changed his sitting. He said, what do you mean? I said because he’s not an engineer. He said, how can you say he’s not an engineer? I said, because I know, I’ve been taught by English people, Polish people, all sorts of people; even Russian people in ABU. I know what engineering is.

Then he said, ‘“but you know he’s free to us”. I said how do you define freedom? He’s free to you because you don’t give him a salary. But you give him allowances, housing allowances, travelling allowances.

By the time you compile all those things, he will be earning far more than what the normal Nigerian lecturer of his level is earning. So the question of being free is not relevant to me.

Then he said, oh, you people of this generation! I said, sorry, sir, but the truth must be told. He said okay.

You were then a graduate assistant?

Graduate assistant? No, they called us assistant research fellows. He said, okay, “but you want to remain with us”? I said of course.

“Now, I know you cannot do away with that person. But if you really want me to be part of your system, return me to my original Department of Mechanical Engineering”. He said, “That’s all”? I said, “Yes sir.”

He said, okay done, and that’s how I found myself back after some months, back to the Mechanical Engineering Department.

How did you get a chance to go for PhD?

Oh, it’s another story altogether. My head of department was a Polish living in Britain. Professor Barnard, we called him.

So, he wanted me to go to Britain because he left his own country, Poland, and was living in Britain, so, he wanted me to go to Britain and decided that he would apply for me, and so on.

At that time, anybody from ABU, or any Nigerian university, had no problem with postgraduate studies in Britain because those who were there before us had proven themselves beyond reasonable doubt.

There was one Egyptian professor of Mechanical Engineering who happened to be teaching in Scotland. He was Egyptian, alright, but he was teaching in Scotland. And he had been in Scotland for so long that he was entitled to sabbatical leave.

And he came to Nigeria and came to ABU in particular to our department. And by some coincidence, the same area that I was interested in pursuing my PhD, was his area.

What area is this?

That was fluid mechanics. So, I found that the coincidence was too good for me to let go. I sat down with him and discussed my interests. But he was a clever person. He knew the relationship between the administrators of the department and the university with religious bias.

If I were to follow him just like that, they would just say that it was a religious dimension that was pushing me there because he was a Muslim, forgetting that even though he was a Muslim, he was teaching in a country that had nothing to do with Islam.

He asked me to write an application for postgraduate studies in Scotland, which I did. And I kept it to my heart and he too was keeping it to his heart.

I knew that my head of department would not approve for me to follow him for obvious reasons. And without the head of the department’s nod, I could not get any study fellowship.

The Egyptian professor asked me to make an application to an organization, UK Technical Assistance in Britain. Eventually, both my admission and the technical assistance got receiving hands.

I got the letter of admission first and I didn’t want to lose a year because this professor actually left four other PhD students he was supervising because he was going to be away for just about one year and they had more than one year to finish.

So, I decided the best option was to come to my home base. I took time, took my letter of admission and came to Kano. I went straight to the Ministry of Education. I said I wanted to see the perm-sec. Everybody was looking at me, this small boy, what is he looking for? You can’t see anybody but perm-sec? I said no, only perm-sec.

Eventually, after some time, I was ushered in. The late Emir of Kazaure, the father of the present Emir of Kazaure, was then the Perm Sec Education.

So, I sat down comfortably and told him all my stories, all my struggles with the American so-called agricultural engineer; the vice chancellor, and whatever. I then told him that this is an option that came up, with the situation or something.

So, he said, how are you sure that you will be comfortable? I said no, we have been with him for almost eight, or nine months now. And we are in the same area and I’m sure he will be my supervisor and I don’t anticipate any problem with his supervision. He said fine.

Then I said, but sir, you know I don’t want to also dissociate myself from the ABU because I’m now getting more interested in the academic area. I don’t know whether if I get a scholarship from Kano State Government, I will be able to go back to ABU when I finish.

Then he looked at me and laughed. He said, “Which ABU are you talking about? I said ABU Zaria, he said is it not ours? It’s ours. Do we have any other university other than ABU in the whole of Northern Nigeria?

“So, if you are going there, are you not being our representative there? Kano would be pleased to help you.?” I said, thank you, sir. So, eventually, within two days, I was able to get my scholarship to Scotland.

But I’d already told him that I had applied to this UK Technical Assistance. That if it comes out later on, I’m prepared to release my Kano State Scholarship for others to benefit from. And he was highly impressed because it was not what most other people would do.

And this is what happened in the end, you got the..?

When I went there, within three, or four months, the technical aid came. And I wrote back to Kano State.

Was it more attractive than the Kano scholarship?

No, actually, it was slightly less than the Kano State one. But both of them would make me comfortable there because I got a good reception in Scotland. So, I wrote back to say this is my condition, they can discontinue the scholarship. And they were very, very impressed.

How was life in Scotland? It’s a very cold country for someone coming from these parts.

It was. Well, initially, I wasn’t coping very well. But eventually, I discovered so many of the tricks. I had been forewarned, especially by my supervisor-to-be, who eventually became my supervisor. He told me how cold it was, and so on and so forth.

So, I prepared myself by having a kind of dressing, like this Kaftan, I can have three or four different sizes. And of course to have a sweater under, and so on, even trousers, sometimes, I could put on two.

So you put many kaftans and many trousers on top of each other?

On top of each other with sweaters below to make sure that the cold is challenged. And after some time, I was enjoying it. It was not a terrible cold really, it’s colder than here, but it’s not the type of cold that makes you very, very uncomfortable.

Once your body is fully covered, you find that you can walk about. In fact, sometimes I enjoy walking on ice. And eventually, I had no problem whatsoever.

Were you with your family at that stage? Were you married then?

No, I wasn’t married. I was betrothed. But that’s all. After the…, what do you call it? I only had her picture in my pocket, wherever I was going.

So, you knew eventually. It’s just a matter of time…

It was a matter of time. So, when I was in Scotland, all my effort was just to finish as quickly as I could and come back home.

So, you didn’t marry until after your PhD?

Until after my PhD.

Tell me about your career. You moved to, of course, you were at ABU for a while, teaching and then there was this move to Kano School of Technology, then later to Sokoto Energy Research Centre. By then, you seem to have shifted to energy engineering. At what point did this solar thing came into your career?

Well, it came as early as when I was an undergraduate in ABU, actually because we had some lecturers from the US and so on, who were into it and somehow, I was interested. But, in fact, some of my colleagues did their final year projects in solar energy. I used to advise them.

In ABU?

In ABU… But my own project was not on solar but I would sit down with them sometimes because I was interested, and give them some ideas and so on and so forth. So I was comfortable really. And fluid mechanics is really very fluid; it’s the right thing for all these kinds of energy engineering aspects.

So when I was in the final year of my PhD, there was one conference about energy in which I became interested. I discovered that even from my work, I could work out two papers for publication and the supervisor supported me in that and I sent them and they were accepted.

Of course, I was able to finish and leave. But I couldn’t get sponsorship from anybody in Nigeria to go to the conference. It was in Bulgaria. They were having an international conference on energy matters and so on, so I became interested.

And when I was back in ABU, I found that I could now put a lot of energy into my interest in energy studies. And I got the opportunity. I was appointed as the postgraduate coordinator for the department, which gave me the opportunity to discuss with all the students their interests and so on and so forth, and post them to the lecturers that were interested in their areas of interest. They were called assistants.

So from then on, I became very comfortable with energy studies and solar energy in particular.

How did the invitation to Sokoto come about? How did you go there?

When I was in ABU, there was an attempt to get me to Kano, I resisted. Then a colleague of mine A. T. Abdullahi, I’m sure you know him, you interviewed him, was cajoled to come and take over as the head of the School of Technology.

While he was there, the civilian government of Abubakar Rimi came in and they manoeuvred somehow to say that his government was going to be that of intellectuals and so on because some of them actually met me in ABU and that I should come and join them, but I said no, no, no. I spent so much time and endured so much cold getting this PhD. Please allow me to make use of it.

They wanted you to be commissioner?

Whatever they wanted me to be there. So they eventually got him, Abdullahi, to become the commissioner and then there was this gap, of who was going to take over the School of Technology.

They said they should come back to me. That was two, or three years after. I said, no, no, no, no. I didn’t want to come home to something. Because, if you know my history, I would have been in Kano several decades ago.

But now that I have spent so much time learning something, let me please make use of it. They said, okay. You don’t have to come on as a full-time staff. You can come on sabbatical.

I said, okay, what is sabbatical? They said, you will come here, we’ll only pay you salary and so on and so forth. And then at the end of every year, we’ll pay your employers’ ABU a certain percentage of your salary so that they can keep your position open with them. I said fine. I accepted that.

After three years, I said I had had enough of the School of Technology because I thought I had done enough to put it on its feet.

It’s administration, really…

Its administration but it was an interesting administration because if you are not in that area, you will not be able to do what some of us were able to do for the school.

To set it up?

To set it up. So, I gave them notice that at the end of the third year of my sabbatical, I was going back to ABU.

Then ABU, ABU, ABU in between, there was a conference on energy in Birnin Kebbi, which I decided to attend while I was still here in Kano.

In the process, after attending the conference in Birnin Kebbi, I said I couldn’t pass through Sokoto without seeing my oga, my friend and oga, Mahdi Adamu. He was then the vice-chancellor. So I went and said I wanted to see him; because we started something with him.

In ABU?

In ABU. About six or so of us, trying to translate some technical terminologies into Hausa and so on. He was the Hausa man. We have scientists, engineers, and so on. So I just went to say hello to him.

When he saw me, he flared up. He said, “Thank God I’ve gotten him”. I said who is him? He said “I have an instruction from the federal government to set up an energy research centre to be based here in the university. And I cannot find any person that I know can do this job for me better than you. You are the President of the Solar Energy Society of Nigeria”.

By then you were already the president?

I was the president then. I said, okay but I have a problem. He said what is your problem? I said I had written back to ABU that I was going back after my sabbatical.

He said no, there is no problem that is not surmountable. So I said okay, fine. We discussed it with him. He said I should send my credentials and so on and so forth.

I said no, but you know, sir, I have never applied for any job. All my jobs, I always get them somehow.

He said, “This one also you are getting it somehow because I’m not saying that you should apply. You have already been appointed.” I said eh-eh, that’s life.

So I came back. While my preparation for leaving the School of Technology was still on but then where was I going? Not to Zaria but to Sokoto.

That’s a new centre you set up?

It was a new centre, I set it up myself

In 1984?

Late in the year. I was deputy vice-chancellor by then because in 1984 I became deputy vice-chancellor around September-October.

That is good. I was in ASUU, so you know about me?

You were in ASUU because I contested for the post of ASUU president and they said if I was part of the problem, I could not be part of the solution. That’s what some of you, in fact maybe you are those who campaigned. But even then, I was beaten by only one vote.

And not only one vote because all my colleagues in the associated faculty, faculty of science, thought that there was no contest between me and the others. They were so sure that I was going to win. So some of them didn’t even bother to attend. So that’s how it happened.

Let me ask you about the centre, which is supposed to help Nigeria solve its energy problems. What is the progress so far? You are the first director. We are still struggling with energy. We are still not able to really utilize solar, why is this so?

No, it’s wrong to say you are not able to utilize solar because we are still utilizing solar energy. In fact, some of us are surprised with the level of commitment to some of the modern governments maybe because of contract attraction or whatever.

But when we started, people in government didn’t even want to hear us. Except those at the very top who thought that there should be this approach, this research.

Our job is to do research and show the way in which we are doing it. You know, two of us were in Nsukka and Zaria.

We are supposed to concentrate on solar energy issues… two others are supposed to be doing media. So we are doing it as best as we could and…it is beyond us to solve the immediate problem of Nigeria. Right now, our problem is not the energy source itself, but the way we make use of the source.

So some of us, when we sit down and look at them, the way some of the state governments are committing money to solar technology, I just laugh.

I said if you had done one-tenth of what you are doing now as government, we wouldn’t be where we are now.

Solar energy is one particular peculiarity. It’s not what you can call a concentrated energy source. I hope you understand what I mean.

Therefore, you don’t expect to be able to generate large-scale power in one location. But that disadvantage is also an advantage because most of our energy requirements in so many areas are not large-scale.

And you can do it by, you know, if you take a local government, you don’t even want to cover the whole local government with one source of energy. You can go to one big town or one small town or one village or whatever and provide simple facilities for solar energy which can serve their present needs, which is upgradable because if you don’t start from the beginning, you can’t reach the end.

So just like all other energy sources, we went into wind also. Of course, hydropower is what has been giving Nigeria most of its energy before then. But all these things are not properly utilized.

There are so many scandalous ways of handling issues. It became just a source of enriching some people who are in authority, which is unfortunate, very unfortunate.

Some of us were really, really very unhappy with the situation and what was happening. But that notwithstanding, on the energy matter, we used to tell people, look this energy is a thing that we have. There was a time that I went to India for an International Solar Energy Conference and what happened then? I was still in ABU in fact. I met some people from the federal ministries. They were there on a different mission, on a trade mission or whatever they called it.

We met in one hotel and then when we were discussing, they saw me; of course, I always dressed like a northern Nigerian wherever I am.

We were discussing and so I said I was there for solar energy conference. I said what is your problem? They said, “You are the people who are trying to degrade the price of our oil.”

I said which oil? I said, you don’t have any oil, my friend. We may have oil underground in our country, but it’s not ours. How many of the people who are drilling it and taking it away are Nigerians?

How can any one of you swear by whatever you believe that you know how much oil is being taken out of our soil and seas? And you are talking about the same people who are promoting this solar energy as the people who are taking your oil. And they know the limitations of oil. One day it will end, it will finish.

So this is the culture that we evolved. As a developing nation, we don’t have to start thinking big. You can go slowly but surely. Take small areas, and give them solar energy. Some give them even wind energy. Some give them small hydro because even the hydro, there are about three or four different categories.

There is the big, large-scale one. There is the medium size. There is fairly big. There is the small, miniature hydro, something that can serve a little settlement.

And the wind?

And the wind can also do that. So if you have a comprehensive plan for energy, which I stopped even mentioning in my annual reports or annual conferences when we go to energy conferences and so on and so forth, because if people are going to listen, all you need to do is to have a plan where you can be developing from one stage to the next, to the next and to the next.

Is it that we don’t have the plan or we have not followed it?

No, we don’t even have a plan.

Up to now?

I don’t think we have the plan because if you take your state for example, the governor or permanent secretary or something will be thinking of giving power to the whole state.

Yes, it’s good to give power to the whole state, but how do you do that? If you think you are going to sit down, let’s take Kano, you sit down in Bebeji or in Gaya and say you are going to prepare energy for the whole of Kano, you are not serious.

You are not serious because the requirement is so much. Even the Chalawa gorge and so on and so forth that we have for hydro can only give a few megawatts of electricity.

Therefore, a plan means you have a strategy of identifying all your sources, where each one has a primary advantage, where the capability is not going to be a serious challenge, and so on and so forth. Gradually as you do it, you keep on improving it.

A plan is as its name says, a plan. It’s not a law but we don’t seem to have that. Everybody will just talk and say by the end of this year, everybody will laugh. Do you want us to cry?

That’s what the political agenda is. Just make very funny statements, but if you don’t have a proper strategic plan, there is no way you can succeed.

Prof. like most academics, you moved on to become vice-chancellor, which is, I guess, what most academics would say is the height of their career. Is this something that you really wanted yourself, or to go to Yola, then eventually to Abuja? Would you consider this something that really capped your career as an academic?

Well, academic career ends as a professor, that is one, the other one is administrative. Of course, if you are in the area, it will be better.

My going to Yola, you know, during the Buhari military administration, he cancelled the status of six universities in the country and attached them to other universities as campuses, which was a good idea.

When Babangida took over, he demerged them so to say and that was when I came in. The then Minister of Education when the demerger took place was Jibril Aminu, a Yola man, of course.

He had been around. He knows the capability of some of us and so on and so forth. So just one day I was asked to go to Lagos.

From Sokoto?

From Sokoto. To go to Lagos, that the minister wanted to see me. I said fine. I went. And after a very, very brief set of greetings, he said do you know why I called you here? I said no, I wouldn’t know.

He said this is the situation. We have these universities, the one in Bauchi, the one in Yola, the one in Makurdi, the one in Abeokuta, the one in Minna and so on and so forth. Minna was not actually merged. The one in Owerri and we have to demerge them according to Mr President, the military president. I said fine. Go ahead and demerge them. What is my problem there?

He said no, it’s not your problem but I will make it yours because you have to go and hide one of them.

Earlier on, they had set up a committee, of which I was a member, with Professor Bajoga who was then in charge of what is now called the ATBU, to look at the possibility of saying the president wants them demerged.

But what is the logistics of doing it? How many of them would be converted to a University of Agriculture? How many will remain as technology and so on? And we wrote that report.

And maybe for that reason, some of our names showed up and originally they wanted me to go to Bauchi.

But then later on, they said Bajoga should remain in Bauchi because the Bauchi campus, which was under ABU then, was being headed by him.

So they said since he knew it well, let him just continue with it. So I was asked to go to Yola. And that’s how I found myself in Yola. I couldn’t say no.

Was it fulfilling being vice-chancellor?

It was challenging and anything challenging can be very fulfilling if you are able to stand on your feet and do what you believe should be done. And that’s exactly what I did.

What happened when you were brought to Abuja for this one year as acting vice-chancellor? That was crisis management?

That was after I finished my two terms in Yola. In fact, I was already back to Sokoto where I belonged. So somehow there was some problem of succession in the University of Abuja. My elder brother, Professor Isa Mohammed, who had been the vice-chancellor then, had his own idea of who should succeed him.

The minister, the permanent secretary, the whatever, everybody seemed to have his own idea.

So, somehow the minister, who was then from Adamawa, said I should be called. So I went. In fact, I was coming from Sokoto, I was going home to Ringim. Normally when I came I stayed in the guest house of the old site, now BUK. when I was passing through.

So, I came this time around, I didn’t even stay there. I wanted to go to Ringim straightaway. Just when I was reaching Ringim, I saw one of my friends; I saw his car coming around my house.

He said he had been asked to bring me back to Kano. I said for what? What have I done? I said is it because I came from Sokoto and I didn’t stay in Kano that I should be brought back to Kano or what?

He said, no, no, no, it’s a directive from the Federal Minister of Education that you should go to Abuja. I said go to Abuja? I said when? He said now, I said, that is not possible.

You were already in Ringim?

I said that was not possible. Then he sent the phone numbers of the minister to me. I said okay, fine. The best thing I can do is that, let me take time to greet my people and then I can come back to Kano today and try to get the minister on the phone to find out why I have to be there at all.

I tried all I could but didn’t get him through until the following morning. And then he said, where are you, are you already in Abuja? I said, no, I’m in Kano now. He said okay, he had already planned with somebody who would come and pick me up. I don’t know how they got to know I was here.

It was really an emergency?

It was an emergency. So I went there. The permanent secretary, who later on became defence minister, said, this is a very short statement, “You are going to come and take over University of Abuja.” I said what have I done to deserve this wahala. I said I spent seven years in Yola trying to build a university. We were appointed the same day with the present vice chancellor of University of Abuja.

If he doesn’t want to go, allow him to continue maybe for life. They said no. It’s not only that he doesn’t want to go but he doesn’t want to hand over to somebody who he does not know.

I said but who says he’s going to hand over to me? Because it is not a proper handing over, since I am not going to contest, I have finished my tenure as vice chancellor, I can’t do anything now.

Even this thing you know, you yourself you are saying, is that I should just act so that I can start the process of getting a proper vice chancellor and hand over and go away.

So they said no, there is no way, I just have to take the job. I said okay, who am I? That is how I took it.

And you finished the acting term and handed over to ….

Yes, by the time I was able to, Prof. Isah was my senior at Barewa College and naturally, we knew each other very well and we knew each other also in ABU. So I went with all sorts of tactics, but he said look, what is there, you were Vice Chancellor of the University of Calabar, you came here to the University of Abuja, as vice chancellor, what is it that is making you lose face with all these people.

I said hand over to them. He said no, no, I can’t do that. I said no, you will do that. I said, after all, okay let me tell you, they have asked me to take over from you. Are you saying that you cannot trust me to give me? And he looked at me and said hmm these people they know what to do.

Prof. did you achieve your ambition of becoming a farmer after all these high-level appointments?

Yes and no. Yes, I have always been a farmer actually because even when I was vice chancellor and so on, any time I find, I leave some money for the farm in my hometown and so on and so forth.

As I said, even in ABU, I was able to get one farmland, very close to the present teaching hospital. It was fairly large and there was a time I was able to farm it all, at that time things were reasonably fair.

And then at home also, whenever I find an opportunity to get a small piece of land, that is close to mine, I farm on them and thereby increase the size.

So eventually I was able to get something but you know farming is a very, very difficult thing. If you are not there, you are not there and no matter whom you think you can trust, you will be disappointed.

No matter who?

No matter who; so eventually I started slowing down on my farming activities and so on and so forth because I found out that by the time I retire, I wouldn’t be able to finance any farming because you will get people, you will buy and get people to go and apply it in your farm…

But I thought also having retired means more time for you to pay attention to the farm?

Unfortunately for me, I only retired but I wasn’t that tired. So I was still doing my lecturing because at the time I spent almost 10 years as a contract officer at Bayero University.

I spent almost 13 years in University of Science and Technology Wudil as visiting lecturer. I spent some time in the University of Maiduguri as visiting professor, all due to some linkages of my own former students.

The first sets of students I took for PhD in Bayero, three of them, all from the University of Maiduguri and three of them, all became HODs and they said, they wanted to start PGD and that I should go and help them.

So you had to. Are you still professor emeritus in Sokoto? Do you still teach?

No, I can’t be going since you know I became professor emeritus and then many things happened, then later on, travelling now has become a nightmare and I can’t undertake.

And since I had some accident, which affected my back and waist and also affected my eyesight, I had to abandon travelling.

So what do you do now in your retirement?

You know, I just rest. Anybody who has an idea, they come for consultation, I can talk, I can advise somebody and so on. Some of my former students still come, they may be still active lecturers, they come for advice and so on and I give it free.

Do you do any physical exercise? Do you move around?

Not much really because like I said, the accident you know affected me a bit.

But did you marry that lady whose picture you had in Scotland?

Of course, she is the mother, we have 10 children and the one that is guiding here is the youngest one of them. There is the other one that is a doctor, then the one that is just outside, the one after him.

So only one wife, all these 10 children?

No, I ventured into, you know I am very adventurous, I ventured into polygamy. There was a time I had three – first of all, from one I went to two, then from two I went to three, then I came down to two and then later on, I went back to one.

From where you started?

From where I started, and one of the other two wives who is no longer with me, gave me another son who is now my youngest child, who is in SS2 and my pleasure now just to see. My pleasure even when I was a vice chancellor and so on.

I am always interested in seeing that not only my own children but any children that are close to me, I make sure to see that they make up and become something in life. And I am happy that in that area I have succeeded.

Thank you Prof. Ahmed Tijjani Suleiman for this insight into your life and viewers thank you for joining us in this edition of Reminiscences and until another time, goodbye.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.