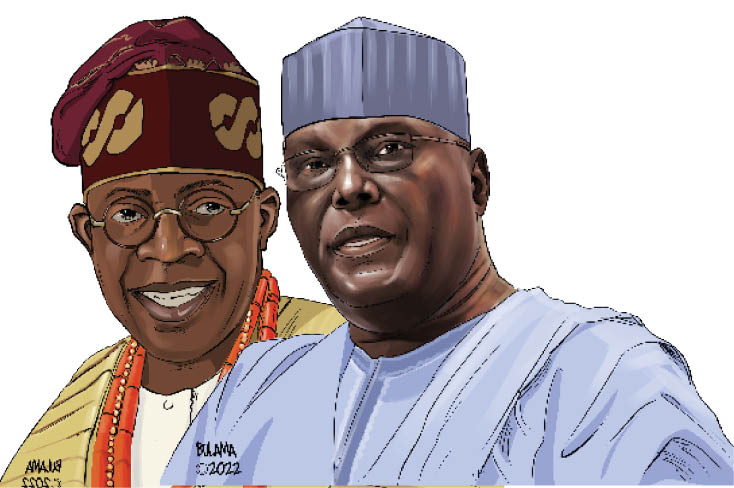

With the conclusion of the APC presidential primaries last Wednesday and emergence of Bola Ahmed Tinubu as the party’s presidential flag-bearer after months of risky horse-trading across all camps, I intended to analyze the predicted Atiku – Tinubu face-off this week, but doing so would’ve been a rehash of an old column. I elected to yield this space today to my column of January 23, 2022 as first published, about the dilemma before supporters of the two political heavyweights who, aside from being friends and business partners, are more alike than they are different. Their face-off is likely going to be the most closely-contested presidential election in Nigeria since the controversial Shagari – Awolowo face-off of 1979. Enjoy.

When former Vice President Atiku Abubakar picked the PDP ticket to tackle President Muhammadu Buhari in 2019, he was cast by the APC as a frightening opposite of their candidate. He was profiled as corrupt and untrustworthy, and even his policy foresight that seemed well-intentioned, like the scandalized promise to privatize the NNPC, were interpreted as the desperate gasp of a crony capitalist. In appealing to the poor then, the ruling party stirred up anti-rich sentiments through populist propaganda, especially in the North, and hired local musicians to announce the coming of their candidate’s closest and wealthy rival as a reign of thieves.

Exploiting the economic shortcomings of the majority of Nigerians, the pro-Buhari camp romanticized poverty and criminalized wealth in telling Nigerians that the rich must not be trusted with the seat of power. The “success” of the campaign was in the refusal to distinguish between legitimate wealth and corruption, lumping the wealthy together as enemies of the state. The episodes of Buhari—who isn’t poor and ascetic as understood by a gullible segment of the underclass—flying in the wealthy politicians’ private jets and thriving on their donations, were conveniently left out in painting Nigerian politics as a contest between black and white, the devil and the saint. This is the brand of populism that plays out every election year and is always deployed to frustrate objective analyses of electoral processes and promises.

Those binary conversations that surrounded Atiku when he ran for President about three years ago have resurfaced since former Lagos state governor, Bola Ahmed Tinubu, pointed to Aso Rock as his next station. His aspiration has instigated quiet infighting in the APC. The arguments against Tinubu’s candidature are the exact words once strung together to oppose Atiku, especially the part that he has unexplained wealth and would favour crony capitalism if elected. Interestingly, defenders of Tinubu’s “corruption”, old age, vague ancestry, academic history and health status are the partisans fond of vilifying Atiku over the same political “baggage”. The two politicians’ profiles and hurdles are almost entirely alike. Atiku’s road to flying the PDP flag in 2023 is only as certain as Tinubu’s chances of acquiring the APC ticket, but the parameter of their capital gives them an edge over other contenders in their parties, and both must’ve been awaiting vicious gangs of “youths” and “technocrats” to remind them that the ticket to Aso Rock isn’t for sale or cut a deal.

If the appearances of the political veterans on the presidential ballot papers next year become inevitable, mutual hesitation of their supporters to cite the opponent’s personal deficiency would be glaring, and that’s because the repeat of the past attacks on Atiku by the pro-APC camp, ad hominem and propaganda likely to be repackaged for renewed antagonism if he secures the PDP ticket again, would cast Tinubu too in similar sabotaging light. Atiku and Tinubu are more alike than they are different.

At 75, Atiku’s age is likely to be emphasized to demarket him, and that seems to be a position already being deployed to damage the Tinubu brand. But if the latter ends up triumphing over other contenders in the APC primaries, many of whom are likely to be his political mentees and beneficiaries, the feared ageism would be de-sensationalized. Both sides, of course, are likely to point to the lacklustre performances of younger presidential aspirants like Governor Yahaya Bello and also the abundant examples of outstanding septuagenarian to centenarian leaders from Mahathir Mohamad to Joe Biden.

It would also be difficult for Atiku’s APC critics to criminalize his vast wealth if Tinubu emerges against him. Both politicians have been fiercely scrutinized by the public and the authorities, and even though none has ever been convicted, Atiku’s investments, which cut across education, media, food and agriculture and shipping, have always been demonized to portray him as a villain of the Nigerian story. But that would be a dangerous path for the APC to tread with a Tinubu ticket. Aside from being also marked for his vast investments in the media, hospitality, and finance, the two aspirants oversee business empires with overlapping interests and have been long-standing allies.

When Atiku fell off a treadmill in the period building up to the 2007 presidential elections, the knee injury sustained and treated abroad was sold to the public by the then ruling party as a hindrance to his performance if elected. The injury featured in the propaganda of the opposition parties in subsequent elections even though his dependence on crutches was brief. Tinubu’s appearance with a walking stick after his recent treatment for an unnamed ailment in London invalidates the possibility of physical fitness being a talking point in a contest between them, at least for the rational partisans.

Equally redundant in the contest between Atiku and Tinubu would be the caricaturing of his ancestry, as done by the APC to the point of approaching the court to prove he’s not of Adamawa descent. He was mischievously presented as a Cameroonian by the APC in 2019 to have him disqualified. This won’t be tenable with Tinubu as his major rival. The former governor has also been a specimen in the lab of conspiracy theories, and wild accounts of his life and past have also been trending since his ambition began to rattle the country. One of such ridiculous theories has had him profiled as an imposter—that he’s not of the Tinubu family tree as identified but a native of Osun state whose alleged actual name is Amoda Lamidi Sangodele.

These obsessions with Tinubu’s eligibility for the Office of the President are manifesting in the very pattern experienced by Atiku in the past elections. The dilemma, perhaps, would be some of Tinubu’s foot-soldiers—who had vilified Atiku for the same history and attributes they glorify in defence of their principal—eating their words. Both politicians, though, would still have to deal with the ageist demographics and the court of public opinion that has long found them guilty of corruption in absentia. But, ultimately, they would be feared by corporate and political establishments in search of a puppet president because neither is likely to be in the debt of some self-styled kingmakers.

Atiku and Tinubu are also similar in their electoral disadvantages. The former Vice President aspires to succeed a fellow Muslim and northerner, and even though his party isn’t ethically obligated to field a southerner or southern Christian candidate based on APC-type zoning arrangement, convincing Nigerians to let another Fulani politician from the North take charge of the chaos of this polarized country next year would be a hard sale. For Tinubu, the electoral calculus is convincing the Christian demographic to endorse a Muslim—Muslim ticket, and his choice of a Northern Christian as a running mate would repel the Muslim North. If they end up at the polls next year, the tough choices would be between electing another Fulani man after Buhari or a Muslim—Muslim ticket.

What can’t be used against the two candidates is their cosmopolitan profile. Atiku’s marital history cuts across southern ethnicities, including a Titi and a Jennifer. Tinubu’s wife was ordained as pastor of the Redeemed Christian Church of God in 2018. It is, thus, difficult to pigeonhole either as bigots or accuse them of nursing some sectional agenda, whether religious or ethnic. If stuck with these options, the politicians’ handlers and supporters would be forced to settle for comparisons and practicality of their preferred candidate’s manifesto. And, again, the court of public opinion would be reopened for a fresh political trial.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.