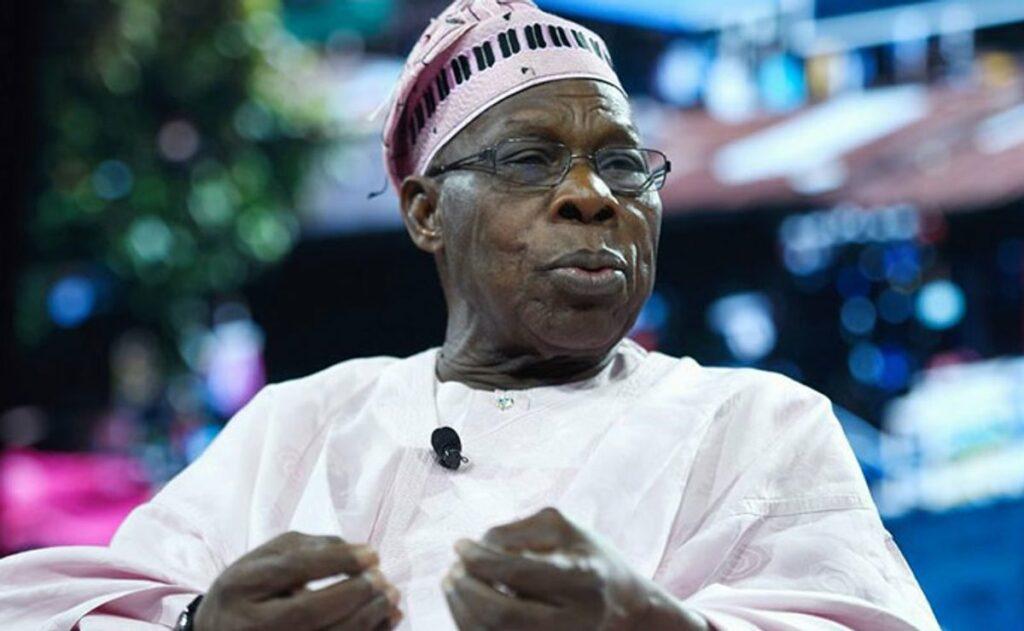

President Olusegun Obasanjo recently harped on the challenges of nation-building, among other critical challenges our country faces at the current bend in its long and no easy trek to that nation of our collective dreams – safe, united, prosperous and in the vanguard of the black man’s liberation.

Nation-building is a monumental challenge. The good thing is that it is a work in progress. A nation that refuses to constantly rebuild itself risks being left behind in the west while the rest of the world marches on towards the east. Nation-building may take the form of radical or revolutionary changes and it may take merely tweaking the system to reset the nation back on course in response to domestic and global developments.

After reading his speech, the best he has delivered in recent times in my view, I took a stroll down the greying memory lane to check on our records in nation-building since the British left us to our devices on October 1, 1960. I found many things that pleasantly surprised me. Our leaders have not generally done badly.

I found that our political leaders, in and out of uniform, have not been remiss in taking on the huge challenges of nation-building. Each of them wanted a nation rebuilt on equity, fairness and justice; a nation not in the abstract sense of geography but one in a humane sense in which all citizens recognise their brotherhood and their responsibilities to one another.

- Living wage: Honour your words, SSANIP charges Tinubu

- Building a culture of environmental sustainability in Nigeria

I found that in responding to the challenges of nation-building our leaders, particularly those in uniform, indulged in experiments, some of which, well-meant as they were, left the nation confused and ultimately in a lurch. In many instances, the solutions became problems and hobbled the nation-building effort. I found that much of the efforts were victims of cynicism, ambivalence, poor commitment to see them through and inexplicable self-sabotage.

Let me give you a brief catalogue of our nation-building efforts from January 1966 when the majors struck. Our first military ruler, the late Major-General J.T.U. Aguiyi-Ironsi, anxious to put his stamp on a new nation rebuilt from the confused system bequeathed to us by the British, abolished the federal system of government and replaced it with a unitary system. He was responding to what he believed Nigerians and the nation itself needed: a single government with unified public services in place of a multiplicity of governments.

His radical change did not stand the test of time. It turned out in the end that what Nigerians wanted was a multiplicity of governments, hence the current 811 governments. Lt-Col (as he was then) Yakubu Gowon who succeeded Ironsi as head of state on August 1, 1966, took a different view of nation building and gave effect to it with the balkanization of the four regions into twelve states. From a federation of four regions, the country made a leap to a federation of twelve states. Gowon, of course, responded to the lingering agitation by the minorities for a breath of freedom from the overbearing majority tribes, each of which dominated the four regions.

It turned out that that simple path towards nation-building fuelled a rash in the creation of more and more states as an all-time cure for all our political ills. We arrived incrementally at the 36-state structure. And then the states, according to the late Chief Obafemi Awolowo, became glorified local governments. Matters would have been much worse if President Goodluck Jonathan had implemented the recommendations of his national conference and created additional 18 states. With 811 governments depending largely on the country’s crude oil earnings, the nation is unable to take giant strides; thus the solution has become a huge problem in the management of our resources.

Sometime during the military regime, someone dragged out of the dictionary a long, fifteen-letter world called marginalisation. It became a new weapon in the contest for how the national cake is shared among, not just among the constituent units of the federation, but also the teaming, rainbow collection of tribes. Gowon responded to this with the policy of quota system intended to give the states and the tribes a chance at the feeding trough. This was later formalised in the constitutional creation of the Federal Character Commission with the responsibility to monitor and ensure that all federal agencies comply with its provisions. It was a pragmatic response to a fractious nation. It is an essential block in nation-building.

The constitution broadly stipulates how the national cake should be done, as in the composition of the federal government should reflect the federal structure. This means it is a constitutional requirement by a Nigerian president to ensure that all the states are represented in is cabinet. Arguably, this would ensure that every state has a voice in all decisions taken by the government. You cannot build a nation without uniting the people.

In the constantly changing kaleidoscope of nation-building, we have tried to superimpose on the states a zonal system for managing our diversities. The six geo-political zones are not in the constitution but they represent non-constitutional efforts at nation-building because they too are intend to effectively moderate and manage our permanent political struggles for comparative political advantages. But this too has become a sheer victim of the capacity of our political leaders to speak from both sides of the mouth and apply solutions as a matter of group convenience.

General Gowon took one of the most radical steps towards nation-building with the creation of the National Youth Service Corps in 1974. He based his action on a simple logic. If the youths are the future leaders of the country, then the country must take steps to expose them to the diversities and the challenges of the country it would be theirs to govern sooner or later. The NYSC was a know-your-country programme. Its has remained relevant all these years. We may not be able to quantify its benefits and relevance to nation-building but the fact that in a nation notorious for policy summersaults it has survived every government, khaki or baban riga attests to the fact that Gowon got it right.

The anti-graft war is part of the process of our nation-building effort. A nation in the grip of corruption cannot make much progress because corruption fouls up everything. We have not had much success with this aspect of our nation building. The more the crack of the AK-47 is heard in the war to put the corrupt out of business, the fewer are the casualties. Aided and abetted by ambivalence on the part of the war commanders, it must go down as the most frustrating war in human history.

We don try.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.