An evaluation suggests Nigeria is still “not ready” to find, stop and prevent epidemics. It calls for lawmakers to fund the country’s epidemic preparedness through growing action on an online portal.

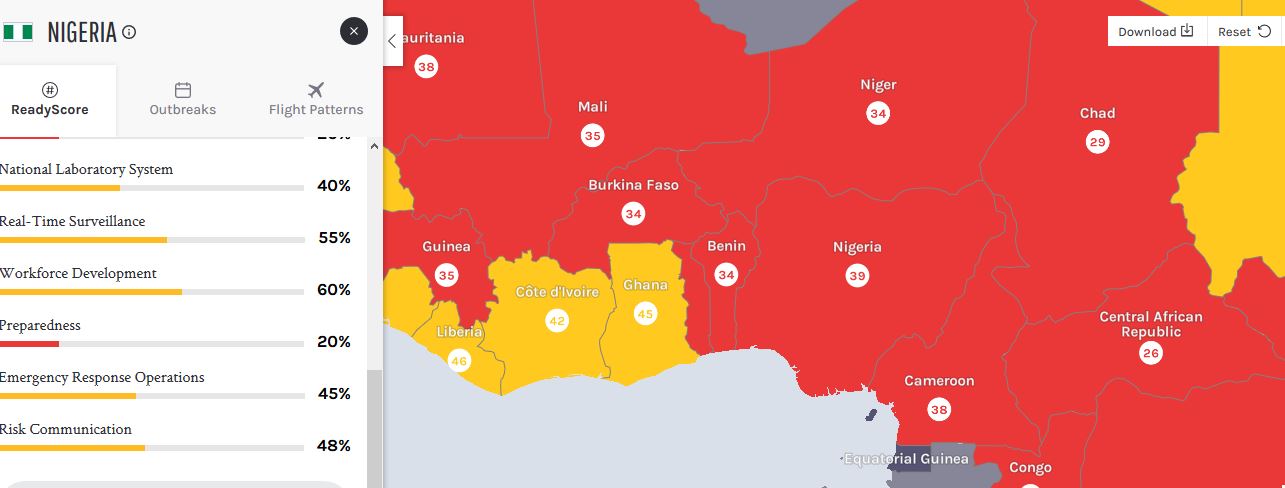

The latest joint external evaluation rated Nigeria as being only 39% prepared. Countries must score at least 80% to be considered fully prepared.

The portal preventepidemics.org notes Nigeria has made progress on certain fronts of preparation but still lagged in critical areas.

Nigeria is scored 60% for workforce deployment, 55% for real-time surveillance, 48% for risk communication, 45% for emergency response operations, and 40% for a national laboratory system, all yellow.

The two areas in which it is in the red are in preparedness at 20%, and another 20% scored for national legislation, policy and financing.

The National Centre for Disease Control has pushed for more reference laboratories, increased surveillance, support for states to institute an “emergency operations centre” and use of digital tools for surveillance.

Up to 211 local government areas currently report on a digital platform, and it is hped every local government will be on the platform by year end.

It has also developed a “national action plan” for epidemics, which outlines multisector roles for stakeholders in health, water, environment, and agriculture.

“We have covered more ground in immunisation, NCDC has helped states set up emergency operations centre, so you now have a command structure,” said Ifeanyi Nsofor, policy advisor at Nigeria Health Watch.

“Sadly, we don’t know of any state that has a budget line for epidemics. They need to have a budget line. Most importantly, the NCDC has to be properly funded by government to do the work better.”

Speaking with Daily Trust on the sidellines of a policy dialogue on epidemic preparedness organised by Nigeria Health Watch, he admitted getting the government to buy into epidemic preparedness was difficult.

A recent analysis estimated it would cost around $80 million of investment to prepare for an epidemic, whereas a full-blown epidemic unprevented could cost $9.6 billion.

“The difficulty is in convincing people that they should prepare for something that hasn’t happened,” said Nsofor.

“The argument we are making is economic: this is what it will cost us to prevent epidemics. If we are not prepared and it happens, this is the cost we have to pay. $80 million versus $9.6 billion. It is a no-brainer. But it is now getting government and different agencies involved to properly budget for it.”

Public health expert, Dr Inyang Asibong, says the difficulty in convincing politicians is in how the health community and politics see things differently.

A former health commissioner in Cross Rivers, she helped push the state health insurance scheme.

The scheme started with costing how much Cross Riverians spend on health care per year: N25,000 on average. The scheme came with a premium of N12,000 a year. The rub was in convincing Cross Riverians they were better off paying N1,000 per month than spending N25.000 a year on health care.

The state governor Ben Ayade affixed his name to the scheme, labelling it “Ayade Care”, and it flew for politics as well.

“You have to speak to them in a language they understand, try to know what speaks to them,” said Asibong about politicians.

“They want their people to see them as working. You can’t just tell [a politician] to bring money for training. Trainings are not tangible. They like to see tangible things.

“At the same time you want to get them to work on things they feel are not ‘tangible’, so you have to look for ingenious ways to get across to them.”

Epidemic preparedness in Nigeria is yet to see that result.

“If for the national plan, we don’t see different agencies putting money aside, that means work done is zero, and we are now going back to donors,” said Nsofor.

“And the donor system is not a sustainable one.”

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.