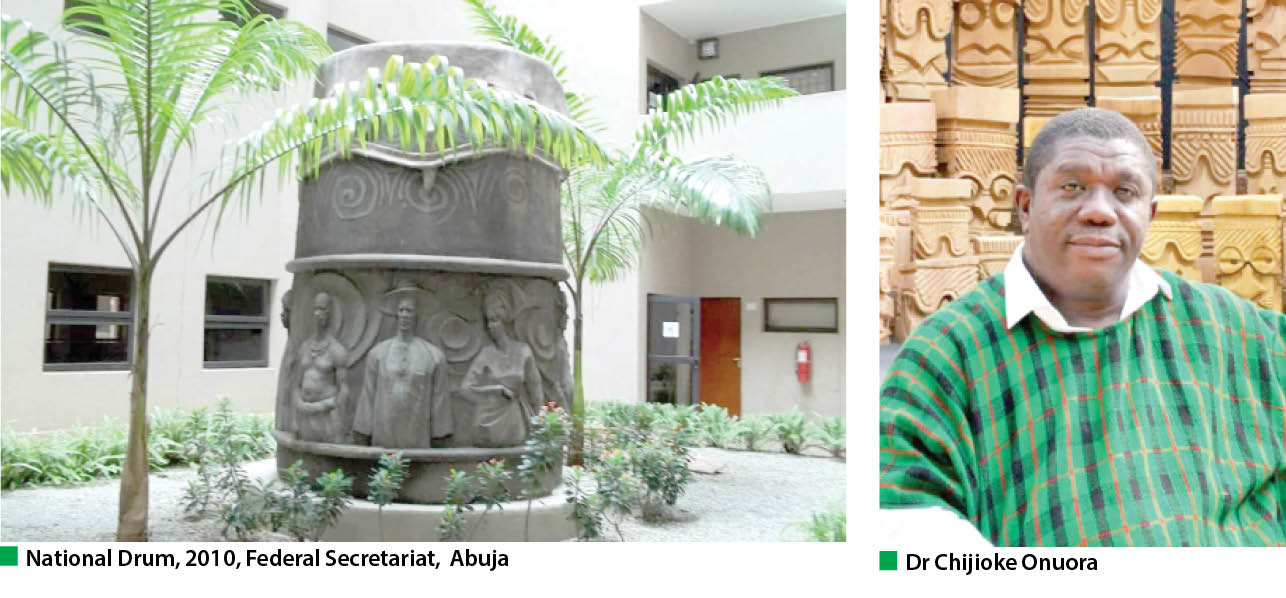

Dr Chijioke Onuora is a visual artist, sculptor and a Professor of Fine Arts at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. In this interview with Daily Trust on Sunday, he shares his experience and lessons gained over the years as an artist.

Can you describe your artistic journey and what initially inspired you to become a visual artist?

The awareness of my artistic calling was sparked by a specific incident in my early life when I learned of my great-grandmother’s skill as an Uli body painter. This talent seemed to run in my paternal lineage, as my town’s most renowned “tailboard artist”, Mr Cornelius Okafor, also hailed from my great-grand-mother’s family.

My journey as an artist began in 1969, aged 7, when I used drawings to illustrate my letter to my dad while he served in the Biafran army. Also, I recall an incident which I playfully refer to as ‘A Rude Exhibition’ at St. Thomas Primary School Oraukwu, in 1970. I felt that the drawings on our classroom wall, intended for teaching aid, seemed not good enough to me, and driven by the belief that I could do better, I seized a piece of chalk and created my own drawings next to the teacher’s own. This act sparked off euphoria in the class, as my classmates jubilantly lifted me onto their shoulders. However, my appalled mother, who taught in the adjacent class, chastised me severely for my audacity. Despite the scolding, I later became the unofficial illustrator for the primary school.

My formal art education began at Oraukwu Grammar School and was further nurtured at Anambra State College of Education in Awka, where I was taught by mostly graduates of the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. I finished from the college with a Distinction in Fine and Applied Arts. While studying for my degree programme at the Nsukka University, a year later, I had the privilege of learning from accomplished artists like Obiora Udechukwu, Uche Okeke, Chike Aniakor and El Anatsui whose influences further shaped my studio art practice.

There’s need for government’s intervention in fertiliser – Gideon Negedu

My most successful works often began spontaneously – Dr Onuora

How would you define your artistic style, and how has it evolved over time?

My deep connection to the traditional art of my community emerged prominently after I completed my degree project, ‘Art Objects of Adazi-Ani Shrines.’ This project led me to explore the original pre-colonial art objects secured in those shrines, and the knowledge obtained from the study significantly began to influence my artistic style.

I also found inspiration in the Uli paintings on the shrine walls and private family compounds, and they gradually began to influence my drawings, paintings and batiks. Prior to this shift, my focus was on naturalistic drawings, particularly of the female form. However, around the 1990s, I gradually began to move away from this approach as the pre-colonial Igbo art influences permeated my work.

What mediums and techniques do you prefer to work with and why?

I received my formal training as a sculptor at the university. Nevertheless, my time at the College of Education exposed me to other areas of art, making me fairly proficient in handling a wide range of other materials. I excelled in multiple studio areas, including batik, drawing, painting and sculpture but my ability to draw remains prominently evident across these different artistic domains. In my studio efforts, I have recurring themes in my works, one of which is “ihe di ibuo ibuo,” which translates to “things come in pairs.”

Could you share some of the themes or concepts that often appear in your artwork?

Notable manifestation of the “ihe di ibua ibua” concept is expressed in the intimate relationship between the male Udo and the female Ogwugwu deities. It is said that even if one is devoted to Udo but neglects the Ogwugwu, it could still lead to dire consequences from Ogwugwu, not minding that Ogwugwu is Udo’s loving consort. I use this relationship as a metaphor to express the relationship between the Nigerian political class and the masses. This theme recurs throughout my work and is occasionally served to the art audience with a touch of humour.

How does your cultural background or personal experiences influence your creative process and artistic expression?

I am attracted to the traditional art of my people, although I do not adhere to the traditional religious belief system. I am a Christian. However, it is essential to note that the artistic forms I create reflect the distinctive art style of my people. For example, if I decide to paint the Last Supper today, you may not see a depiction of male blondes with blue eyes; instead, you would likely see images that were derived from the local sculpture forms. This stylistic consistency is a recurring feature in my art, be it drawing, sculpture, painting or batik.

Beyond traditional art objects, I have a deep appreciation for folktales, proverbs, idioms, songs, poetry of my people, and they play vital roles in the interpretation of ideas and situations expressed in my artwork.

For me, art serves as a language, a means of self-expression, and an extension of my identity. It allows me to convey who I truly am to my audience. I am not an overtly very serious individual but a light hearted individual. Nevertheless, the underlying messages from my work are often profound and remarkably serious. That is the paradox. It is very much like a nurse administering chloroquine, coated with some sugar on order to make it more palatable. This is the therapy my art offers to those who experience it.

Are there any particular artists or art movements that have had a significant impact on your work?

During my formative years, my artistic aspirations initially leaned towards emulating artists like Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and Rembrandt. By age twenty, my focus shifted to Pablo Picasso, George Braque and Paul Cézanne. However, everything changed when I immersed myself in the traditional art of my people, and works of artists like Obiora Udechukwu, Ben Enwonwu and El Anatsui became my new benchmark. Obiora Udechukwu’s use of Uli forms to comment on societal challenges profoundly influenced me. While studying at Nsukka, I adopted the Uli language to convey my own messages, albeit with my unique approach. My artistic style also evolved significantly under the mentorship of Seth Anku, a Ghanaian-born painter and fountain maker and when I lived with him in 1987, I produced scores of drawings influenced by his unique style of drawing made with the shaft of compressed charcoal.

As a student of El Anatsui, I was introduced to unconventional thought processes and innovative material handling. Power tools replaced traditional tools, such as chisels and sandpapers. We ventured into using tools like angle grinders, drilling machines, routers and chainsaws, requiring a shift in our skills and techniques. These experiences moulded me into the artist that I am today, blending traditional influences with contemporary innovations.

Can you walk us through your typical creative process from concept to finished work?

My most successful works often begin spontaneously, as I pick up paper and start to scribble. Ideas take shape naturally, sometimes inspired by discussions, deep thoughts or moments of laughter, joy and pain. These ideas can stem from proverbs or amusing stories that catch my interest. At other times, it is the materials themselves that guide my creative process. Some of my drawings are completed in just 15 minutes. Then, I begin to choose the successful ones to develop further in my batik studio efforts, modelling, wood shaping or paintings. This creative process defines my art and reflects my deep sympathy for lines in drawing.

What challenges do you face as a visual artist and how do you overcome them?

A critic once advised me to focus on one artistic medium for greater success, but my innate drive to explore various artistic expressions makes this a challenge. Look, I am also passionate about music, drama, theatre arts, storytelling, and more, which leads to a lack of in-depth research in any one area. However, in the past two decade or so, I’ve made a conscious effort to primarily work with wood and spend more time drawing. Many of my recent works, especially those in my 2014 solo exhibition titled “Akala unyi,” have focused on drawings while my 2022 solo show in Lagos focused on wood. I’m currently preparing for an exhibition exclusively featuring Batik creations.

How do you find inspirations when you’re creatively blocked?

I often feel an urge to draw when I’m in a good mood. I also write some poetry during such moments and when I am feeling blue. In my younger years, I was still able to work even in the midst of my noisy friends, but nowadays, I prefer working in quiet and serene spaces, once I start working, inspiration flows in naturally, as I interact with the materials, be it charcoal, paint, or carving tools. When the ideas are not coming, I spend more time listening to music or reading poetry.

Are there any memorable or significant moments in your career that have shaped your artistic path?

I mentioned some moments when I made pivotal decisions in my artistic journey. Each one holds significant importance. The memory of my early primary school years, when I boldly drew near my teacher’s work, carries its own weight of significance. Studying art at the College of Education and graduating as the top student in the Department marked another significant milestone. Collaborating with my lecturer, Anku, to create nine life-sized sculptures immediately after graduation in 1986 was also a remarkable feat. Equally significant was my immersion in the traditional art of my people, which completely transformed my artistic vision in terms of forms and ideas. By critically assessing and celebrating my community, I extended my admiration to the broader community as well. It’s akin to sharing my voice with the world from my own small corner, and that corner happens to be my community.

Could you share a specific project or artwork that you’re particularly proud of and explain why is meaningful to you?

In 2010, I had a major commission at the Federal Secretariat in Abuja, where I conveyed a plea for unity through four sculptures. One piece featured the National Drum, symbolizing our diverse tribes, while another, “Sonic Statement”, was an interactive stringed executed with metal sheets and springs. “Precious Things” depicted unity through two wings, one weaker and the other, stronger, and protecting the same set of eggs. “Upward Thrust” shows the beauty of working together. These expressions represent my prayer and desire for unity in Nigeria.

How do you see the role of visual art in society and what messages or emotions do you hope to convey through your work?

If visual art disappears, I wonder what can take its place. All forms of visual arts are outlets for human ideas and emotions. Artists should have the freedom to convey their truth without coercion. Art transcends money. It is a channel for self-expression, critiquing power, expressing emotions, and celebrating virtues. My art will continue to speak even when I am gone.

What advice would you give to emerging visual artists looking to establish themselves in the art world?

They should follow their hearts. You know, there are people who create art with the aim of changing their society. Others do it to make money, and some do it simply to express themselves. Whichever path one chooses, so be it, but it is essential that they express themselves genuinely. However, I believe that the most significant aspect is when their story, their prayers or their commentaries are sincere and have the power to bring about change. That is when their art truly succeeds.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.