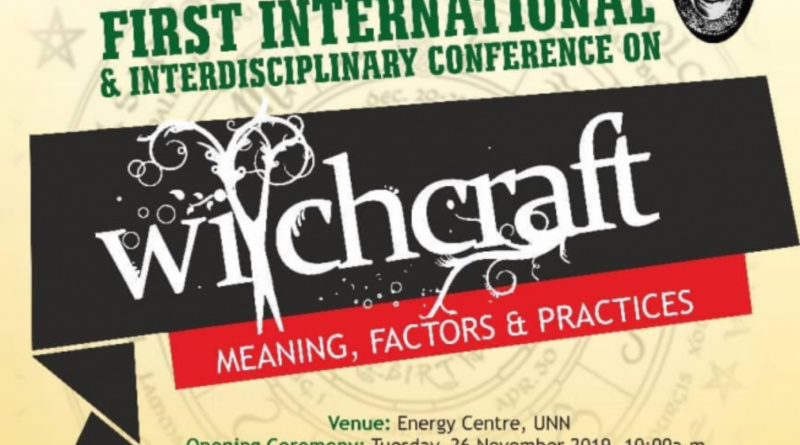

I was quite pleased that the controversial International Conference on Witchcraft at the University of Nigeria, my alma mater, held as scheduled, despite opposition from right-wing Christian bodies and other busy-bodies. The conference, organised by the Prof. B.I.C Ijomah Centre for Policy Studies and Research, UNN, was strongly resisted, with pressure mounted on the University authorities to cancel the conference. It is to the credit of the organisers that they stood their ground though they had to change the theme of the conference from the initially proposed “Witchcraft, meanings, factors and practices,” to “Dimensions of human behaviours.” I believe the academia should be a citadel for interrogating all ‘interrogatables’. For the witchcraft conference, whether it was for academic purposes or for those who claim to be practitioners, the important thing is the element of critical inquiry embedded in the decision by a research unit of a University to organise such a conference.

But it is not only the pervasive fear of witchcraft that is our problem. The fear of anything remotely paranormal or occult is palpable. For instance during the Dana Air crash that led to the loss of over 150 souls, some residents of Iju-Ishaga, a suburb of Lagos where the Dana airline crashed into buildings on June 3 2012, reacted negatively to proposals for the mass burial of unidentified victims in the area on fears that the ghosts of the departed would come to torment them. One Idayatu Ali, a 24-year-old unemployed resident of the area was in fact quoted at that time as saying: “This is no superstition; I have witnessed where a young man died in an accident and his ghost continued to cry at the scene for days until a sacrifice was performed.” Ms Ali was further reported as saying that if the authorities went ahead with their plan for a mass burial of the unidentified victims in the area, many residents would be forced to relocate to another area. There is a strong suspicion that one of the grounds of opposition to the idea of mass burial is the traditional belief that if the dead are not properly buried with all the rituals and rites, their spirits may be wandering and seeking vengeance on the living.

In 2009, the police in Kwara State brought opprobrium to the country by ‘detaining’ a black and white goat, which some vigilantes seized and accused of being an armed robber who used black magic to transform himself into an animal after trying to steal a Mazada 323 car. Years ago, some people in different parts of the country were lynched because they were accused of mystically stealing some men’s manhood just by shaking hands with them. Beliefs like these are common across the country, justifying the witchcraft conference – whether academic or not: if those who claim they practice witchcraft or juju say they want to, that will be fine with me, provided we will have magicians and others who can understand the principles of their assumptions to interrogate them. This is what the spirit of critical inquiry is all about. I believe it is time we carried honest conversations about our belief systems and how they impact on the type of solutions we seek for the problems that confront us as a nation.

It must be clarified from the onset that belief in the occult and the paranormal is not peculiar to Africa. However while the belief in the existence of witches, occult and other paranormal phenomena exists in all cultures, there is something untoward about the way this belief is expressed in Africa, which has led some to conclude that our belief systems are at least part of the reasons why the rest of the world have left us behind in political and economic development. Perhaps the African cosmology, which is intensely spiritual, predisposes us to a pattern of belief that verges on the superstitious. Traditionally Africans believe that up above is the abode of God, the Creator and Supreme deity, and that below the earth is the world of the ancestors – or the living-dead – who exercise some influence over the affairs of the living. They also believe that spirits – both good and malevolent – inhabit the earth with humans and that each person is assigned a personal ‘chi’ (guardian angel), not only to help him/her ward off the perceived evil designs of the malevolent spirits but also to intercede on his/her behalf in the ancestral world and the world of the Supreme God. Perhaps this intensely spiritual nature of our cosmology is one of the reasons why many Nigerians find supernatural explanation for virtually every occurrence, creating in the process avenues for brisk businesses for ‘smart’ pastors, Imams and babalawos.

How do the African belief in the supernatural and the occult differ from the way such beliefs are expressed in say the Western culture? Let me illustrate this with just one example:

One of the celebrities thrown up by the 2010 World Cup in South Africa was the German Octopus Paul. The then two-year-old psychic cephalopod, now late, achieved global fame for correctly predicting all of Germany’s World Cup matches, including their two defeats by Spain and Serbia. It also successfully tipped Spain to win the World Cup – predictions that reportedly led to the mollusc receiving death threats from Dutch fans as it did from German supporters in the two occasions it successfully predicted German defeats.

One significant thing about Octopus Paul’s predictions was that his method was transparent: it got the choice of picking food from two different transparent containers lowered into his tank and the container he opened first was regarded as his pick. Were Octopus Paul owned by a Nigerian (or perhaps any other African), and the animal correctly predicted the outcome of one or two matches during the World Cup, it is most likely that the owner would paint his face and eye lashes with the weirdest chalk around, build a mysterious grove for the creature (and if possible let decomposing corpses litter the pathway to the shrine) and spend the better part of an hour chanting incantations whenever any customer showed up. There would of course be high priests and worshippers of the creature. Additionally, unlike Octopus Paul whose psychic power was apparently limited to predicting football matches, the African owner would definitely claim the octopus would predict any event, heal any disease and infirmity and even tell you the person ‘blocking’ your success in life. While Octopus Paul announced his retirement from predictions just a day after the World Cup, for a Nigerian owner, the proper deification of the creature and the associated lucre would start after the World Cup. Again while there was an official announcement about the death of the mollusc in its German aquarium on October 25 2010, a Nigerian owner would contrive immortality for the creature. While for most Westerners Octopus Paul was essentially part of the entertainment for the World Cup – the way the Vuvuzela was – were the octopus owned by a Nigerian, the little manifestation of psychic ability would have been defined as the ‘main reality’ of life, while our world of reason and critical inquiry would be presented as at best ‘virtual reality’. Again while the psychic successes of Octopus Paul never led to a generalised belief in the West about the reliability of its predictions, were the creature owned by a Nigerian, the mere fact that the octopus achieved 100 per cent success rate at the World Cup will mean that whatever he says (or is contrived to have said) in the future, would be taken as gospel truth – not mere prediction with a reasonable chance of error. Just imagine the number of diviners, imams and pastors who have created eternal enmity in families and communities by fingering people who are probably innocent, as the cause of other people’s misfortunes.

So do witches exist? Anything that has a name probably exists in one form or another. Additionally whatever a person intensely believes in exists for that person. While I am not totally discountenancing the existence of esoteric phenomena, I feel there is something that does not seem right the way occult and esoteric tales are bandied around in the country – often without the opportunity to subject the numerous claims to public scrutiny. One of the consequences is that tales of paranormal and occult practices – of people who could make your manhood disappear simply by shaking your hands, of women who could use ‘love potion’ to ensnare you into marrying them or to do their wishes, of people turning into yam tubers simply from wearing Okada helmets – are a daily staple, instilling fears, even paranoia, in the hearts of many.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.