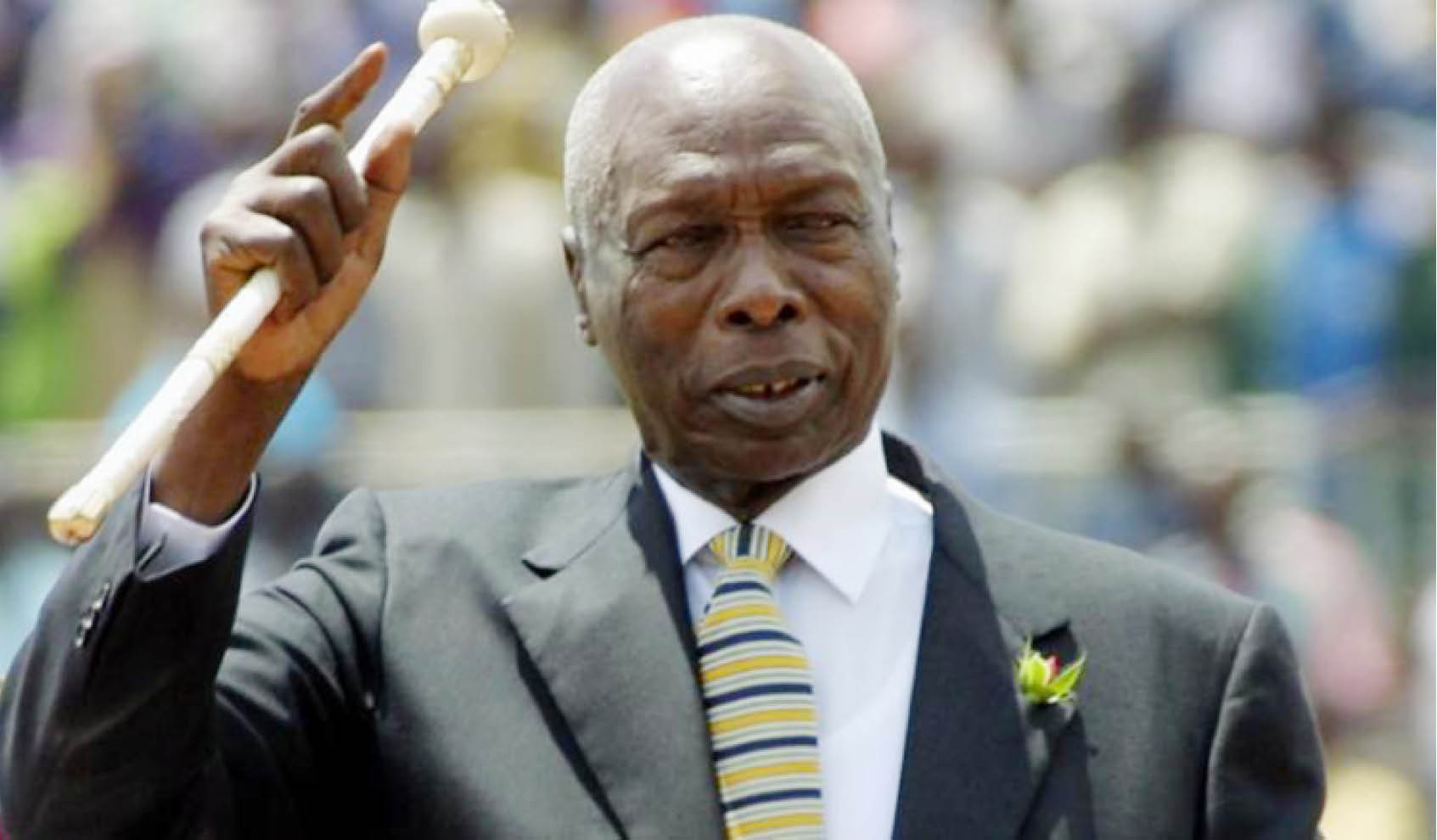

For a nation accustomed to first President Jomo Kenyatta’s fly whisk, the shift to Daniel arap Moi’s ubiquitous rungu, a small, often-decorated wooden baton that defined his rule, was interesting.

It signified a small change in the presidential appearance of a man who had openly declared his readiness to follow in the footsteps of his feared predecessor.

The rungu, that almost remained glued to his right hand for the 24 years he was in power, from 1978 to 2002, perhaps indicated the shift of power from a revered independence hero to a nondescript power player inaptly described as a “passing cloud” by those who controlled the State and saw themselves fitter to succeed Kenyatta.

The story

Moi never spoke publicly of the significance of the rungu, also popularly referred to as fimbo ya Nyayo, Nyayo being one of the names used to refer to him.

Its origin story is of young men of the Tugen community in Baringo (Moi’s Kalenjin sub-tribe), who were implored by their elders to carry an assortment of small weapons to protect themselves against wild animals.

According to his biographer, Andrew Morton, Moi picked up the habit and carried it to the highest office on the land.

“From a young age Moi was always armed with a rungu, a bow and arrow, or occasionally a small sword, to ward off attacks by leopards, eagles or baboons,” Morton says in the book ”Moi, the Making of an African Statesman”, which was first published in 1998.

Iron-fist

However, when he started schooling in Kabartonjo in 1934, where he also converted to Christianity and was forced to abandon many cultural engagements, he dropped the Tugen’s weaponry to espouse the tendencies of a modern man guided by missionaries.

But this was only temporary; Moi returned to the rungu soon after becoming President in 1978, following Kenyatta’s death.

For the next 24 years, Nyayo, as he was called during his reign, used the club to symbolise his iron-fisted rule, characterised by bullish declarations and suppression.

Warrior

According to Lee Njiru, Moi’s long-time press secretary who served shortly under Kenyatta, the fly whisk symbolised blessings for the nation he inherited from the brutal colonial regime.

Mr Njiru said Moi replaced it with the baton to affirm his readiness to fight for Kenyans.

“Mzee Kenyatta became the President at 71, an old man. He was not a fighter and his role was to bless the country and to lead it. Moi became President at roughly 53 years [of age]. He was supposed to be a warrior. The rungu was to fight for Kenya, not to fight them,” the man, who served Moi for 42 years, told a local TV station on Thursday.

The rungu completed Moi’s appearance and, apparently, deficiency reigned without it.

Special delivery

Mr Njiru in the past narrated how a new rungu was flown from Nairobi to Sydney, Australia, in 1981, after the one Moi carried to a previous tour of the United States broke.

Moi had to fly straight to Australia after the US trip and the new rungu had to be delivered to him before he got off the plane in Sydney.

Mr Njiru said an assistant named Peter Rotich delivered the baton right on time.

Praise, Criticism

That the rungu played a key role in Moi’s rule is not in doubt but it attracted praise and criticism in equal measure.

The Kariokor Friends Church choir composed a song titled “Fimbo Ya Nyayo” that praised Moi’s rule.

The baton was also on the flipside of the Sh20 and Sh100 notes that were printed during the Nyayo era.

It is also a significant part of Nyayo monuments across the country, the most conspicuous one being at Uhuru Park in Nairobi.

However, several myths were linked to the baton, one being that it carried mystical powers and that those who dared steal it did not live to tell any tales.

The importance of the rungu may now be confined to the national museum for future generations, if Moi’s family permits it.

Moi died on February 4 after a long illness and will be accorded a state funeral and then buried on February 12 at his Kabarak home in Nakuru County.

DAILY NATION

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.