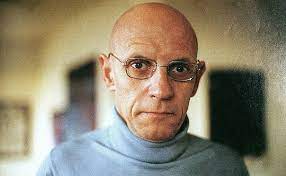

French philosopher and historian of ideas, Michel Foucault, who died of complications from AIDS in 1984, was one of the most original and controversial intellectuals of the 20th century. His work straddles across many fields in the social sciences and humanities, from anthropology to psychology and sociology and from history to literary and cultural studies. The same intellectual thread runs through these various fields, however. Foucault was primarily interested in the connections between power and knowledge and how both shape social interactions and institutions, like governments, schools, hospitals and prisons.

Unlike many thinkers before and after him, who conceive of power as being concentrated in a few centres, Foucault thought that power is everywhere diffused in society, not just in government or politics. One such space in which social power is to be located is language, or what he calls ‘discourse’. For Foucault, the way we speak about things and the things we say when we do are themselves forms in which power is produced, transmitted or exerted by one social actor on another. For Foucault, discourse reinforces the domination of one person or group by another, such as, for example, a fairly common statement like ‘women are less intelligent than men’, which in turn implies that they must remain in their place.

Consider, for example, the way the ‘international community’ speaks about Africa. ‘We want to help Africa; or to lift Africa; or develop Africa”. This mode of speaking, repeated countless times every day in many African countries by foreign or local officials of multilateral organisations like the World Bank and IMF, or non-governmental organisations and so on, express not only a desire for what is said but also what is not said: namely, an unequal power relation between the speaker and the audience. The whole picture will change once we can speak also of how Africa ‘helps’, or ‘lifts’ or ‘develops’ Europe.

But to bring the point home, consider also how Nigerian political leaders speak about Nigerians and what they say; or how lecturers speak to their students in the universities, or how doctors and nurses speak to their patients, or how husbands speak to their wives—or men to women more generally—in our society. In Foucauldian terms, across all of these varied contexts, language use is discursive, that is, it positions those involved in ways that also demonstrate the power relationships between them and hence mark the boundaries of what can be said or not, or what is acceptable conduct or not.

This is probably a poor rendition of an abstract and complex idea, but since reading Foucault many years ago in Britain, I have wondered if he were not writing about Nigeria specifically, which of course, he was not. Nigerian politics and society too is filled with dominant discourses about not only what can be said, but in fact about what can be believed and what can be accepted as true or having happened, regardless of the evidence. If I thumped my chest on Facebook that there was a ‘Massacre’ or ‘genocide’ last year in which hundreds of Nigerians were killed, then I would most likely be hailed by many as a ‘hero of the people’. But if, on the other hand, I said there was none because no evidence of such exists to date, then I would probably receive much online abuse, be unfriended by many, or worse.

If to give yet another easy example, I said that the federal government must pay compensation to the families of the protesters who were killed by the military during the #EndSARS protests last year, my statement will be considered normal, appropriate and the right thing to say, whether or not it is rooted in verifiable fact. But if in the same, vein, I said that the federal government must also pay compensation to the families of farmers and fishermen killed in Yobe or Borno state arising from their ‘accidental’ shooting by the Nigeria Airforce, my statement would sound unusual and unheard-of to many the same people who had praised me for my speech on the victims of #EndSARS and even unacceptable to some.

This is power in the discursive sense as Foucault conceives it because the only difference between each pair of my statements above is the people involved in each case. Compensation resulting from state aggression is acceptable if the victims are X, but not if they are Y. Discourse, in this sense, can determine who gets what and who does not, and its function as a form of power should no longer be in doubt. After all, victims of police brutality have received or at least been awarded compensations by the Lagos State judicial panel. But no one in Nigeria has even thought of constituting a judicial panel to investigate the excesses—intended or not—of the military in the North East these past dozen years. Not even a whisper about this.

This discursive power is rampant in Nigerian politics and is daily entrenched by a media that should otherwise know better. But at this point, let me give a few examples of how this form of power works in Nigeria at much deeper levels. A small story tucked away somewhere in the Punch newspaper of October 15 reported that the House of Representatives has passed South East, South West, North Central, North West commission bills.

The report noted further that “all the six geopolitical zones will now have development commissions, as the Niger Delta Development Commission already exists for the oil producing states… and there is also the North East Development Commission, which was established in the aftermath of Boko Haram insurgency”. Moreover, each of the bills sought to justify its enactment via claims that are quite intriguing, if also comical. The bill for the SEDC, for example, seeks the commission to ‘serve as a catalyst to develop the commercial potentials of the South East, receive and manage funds from allocation of the federation for the rehabilitation, reconstruction and reparation for houses and lost businesses of victims of the Civil War, and address any other environmental or developmental challenges; and for related matters.’

All the other three bills were similarly justified. Now, of course, one can read this as an illustration of the poverty of imagination in our elected representatives on how to make the country or its constituent parts better. We can also see it as a way of attracting federal largesse for capture by local elites. But I see it more as a clear example of how discursive power sets the boundaries of what is politically possible, or not, in Nigeria, because the only substantive reason for the idea of multiple zonal development commissions is the very idea that there should be one for the North East.

The Civil War ended 50 years ago and was followed by a significant programme of reconstruction, even if unfaithfully implemented. Why use that as a basis for a development commission now? Because there is one in the North East. The South West does not even have any conflict to justify its claims but it wants one nonetheless, again because there is one in the North East. And the other zones in the north have simply followed suit. But when the NDDC was being established 21 years ago, nobody thought of a similar agency in the South East or anywhere else for that matter. Why? Because it was all seen as the right thing to do and indeed it was.

But no amount of human and material devastation in the North East is sufficient for people to accept that it can have a commission of its own; hence, one there must be followed by one everywhere. The invisible and unstated discursive power at work here is the deeply entrenched notion that northerners do not deserve anything more from the Nigerian federation—regardless of context or specificity—because they have already taken everything. If they must have, then so must everyone else. More than that, discourses of this kind permeate everywhere in Nigerian politics. We must tear them down.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.