It was a sunny day, a year ago when a colleague referred his son to me. The boy had obtained admission and scholarship into a prestigious flying school in the United States. His parents were so proud of this achievement. Not only had his son, Tunde*, scored all A’s in his WAEC and IGCSE, he had also gone further to apply to all major flying schools around the world seeking admission and scholarships, without any help. Flying was a childhood dream of his and knowing that his parents could not afford to send him to the school he dreamed of, Tunde put his heart and might into studying so that he could meet the admission requirement.

The school offered a conditional admission and required a medical certificate of fitness among other things before confirming his place at the school. When I met Tunde, I was impressed by his enthusiasm and drive. We chatted cheerfully about life while I filled the test forms. Some of the more specialised tests required needed the attention of other specialists and so I called my colleagues in other departments to assist him. I wanted everything to go smoothly for this young, charming boy.

A few days later, my friend in the ophthalmology department called me with his findings. A thorough examination of Tunde’s eyes showed he had a rare condition called Retinitis Pigmentosa, popularly called ‘Night blindness’. My heart sank.

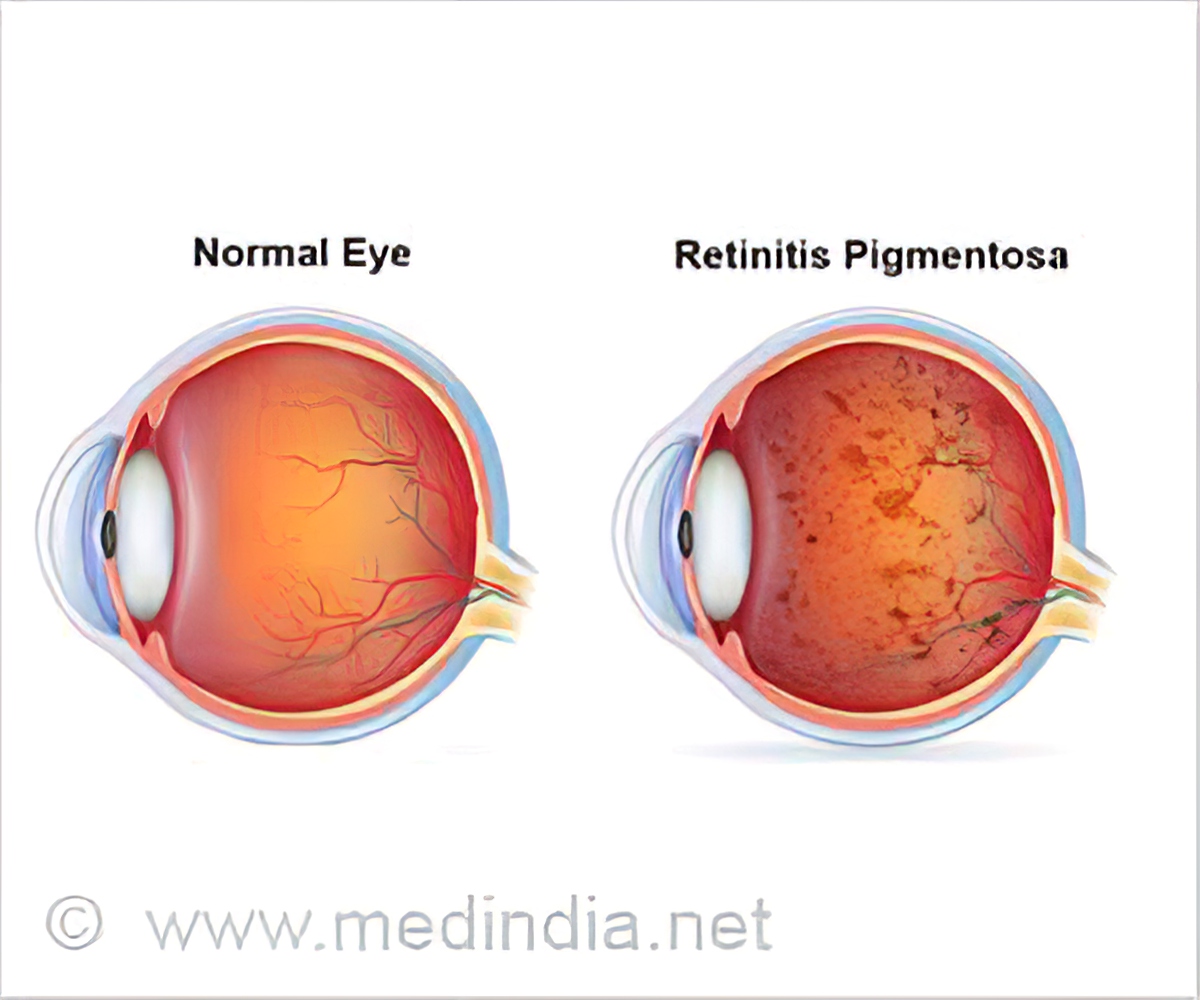

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is a term for a group of eye diseases that can lead to loss of sight. What they have in common are specific changes the doctor sees when they look at your retina; a bundle of tissue at the back of your eye. When you have Retinitis Pigmentosa, cells in the retina called photoreceptors don’t work the way they’re supposed to, and over time, you lose your sight. It’s a rare disorder that’s passed from parent to child. Only 1 out of every 4,000 people get it. About half of all people with RP have a family member who also has it.

Retinitis pigmentosa usually starts in childhood. But exactly when it starts and how quickly it gets worse varies from person to person. Most people with RP lose much of their sight by early adulthood. Then by age 40, they are often legally blind. There’s no cure for retinitis pigmentosa and the most that can be done is to help slow disease progression and help with low vision aids.

His other tests were all normal and so when he returned, I started with the good news first. All his blood work, urine toxicology and hearing tests were within normal limits and therefore fine. I then proceeded to break the bad news as gently as I could. There is simply no easy way to tell someone that he or she is going to lose their vision.

His father had accompanied him, so I started by asking the father if there was any history of eye problems in the family for which he replied in the affirmative. Before his demise, Tunde’s grandfather was completely blind. The cause was however unknown as the old man lived in the village. Tunde’s father denied any visual problems which made me realise that Tunde’s RP was maybe autosomal recessive.

Autosomal recessive RP; Here each parent has one problem copy and one normal copy of the gene that’s responsible, but they don’t have any symptoms. A child that inherits two problem copies of the gene (one from each parent) will develop this type of retinitis pigmentosa. Since two copies of the problem gene are needed, each child in the family has a 25% chance of being affected. Similar to the way sickle cell disease is inherited. Tunde was the first of four children. I asked him to bring the other children for assessment.

As expected, the news devastated both father and son and I urged them to get a second opinion before sending the results to the school. A week later, the father called to tell me that the results were the same, Tunde did in fact, have Retinitis Pigmentosa. He asked me to go ahead and send the results to the school as required.

A few days later, Tunde’s father called with sad news. The school had written to say that his admission was revoked due to his condition. Tunde cried his heart out and refused to eat or come out of his room. When his grief continued for weeks, his mother dragged him from the room and brought him to the hospital.

Gone was the charming young lad I met months ago; in his place was a dishevelled, cachectic and gloomy person. This boy who was previously full of life, confided in me that he was contemplating suicide. He was severely depressed and saw no need to continue life. His mother and I counselled as much as we could but I knew he needed much more than our words. When I mentioned admission in a psychiatric ward, his mother was adamant. She did not want her only son in a psych ward. We put heads together and came up with a solution, he would be admitted, but in a private hospital and managed by a psychiatrist.

Tunde spent two months in the hospital on medication and therapy. Gradually, the depressive symptoms reduced and suicidal ideation stopped. At home, he was encouraged to try and apply for other courses in the university. He confessed to me that the only thing he loved apart from flying was animals. He had many pets at home: cats, rabbits, dogs and tortoises. He had a cat who had been with him JSS1. The cat had helped him through his depressive phase and was with him throughout his hospital stay. They slept and ate together! Apparently pet therapy is not only for Caucasians. I suggested veterinary medicine or zoology and he said he would think about it.

His father called a few days ago to tell me that Tunde had gotten admission to study veterinary medicine at a university in the US. Based on a strong motivational statement he had written highlighting his journey from diagnosis of Retinitis Pigmentosa to him being denied his dreams of being a pilot and his subsequent battle with depression and admission in a psychiatric hospital, he was awarded full scholarship with the only caveat that he maintains his GPA at 3.5 and above. His parents were overjoyed, but most importantly, Tunde’s confidence was restored and his mood had improved

Retinitis pigmentosa is not an easy diagnosis. Till date, there are only numerous clinical trials without a specific treatment. The reality that you will gradually lose your eyesight requires herculean resilience to go on with life. I am happy he chose veterinary medicine as it is a versatile career that can accommodate his disability in future.

This morning I woke up thinking: what if he had not had the eye test earlier? What if he had received his pilot training? He would have finished his training, started work only to have visual problems and go into early retirement at a young age.

We plan and God plans, but ultimately, He is the master of all planners.

Man proposes, God disposes.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.