It was a Saturday, a day when most people were either relaxing at home or attending function. However, parents clustered under a shade beside the black gate of Government College, Victoria Island, Lagos – their faces were a combination of excitement and exhaustion as they received their children who had just concluded the National Common Entrance Examination.

As the kids filed out into the warm embrace of their parents, one could tell that their experiences were not the same.

“They paid money so that they would teach that girl..” were the words that attracted my attention from the conversation among Air Force Primary School pupils, who had formed a small circle away from others. The pupils, four girls and three boys, could not hide their irritation.

Lagos Island, where anything is possible

I had walked into Honeyville Schools as an aunt seeking to enroll her nephew into the school. The school is hidden amidst a line of closely-built houses in Tokunbo Street, Lagos Island.

“Good morning. I am here to make enquiries about enrollment,” I said to a stocky man with low afro hair in a cubic-like room that served as the administration office. Uncle Dayo offered me a chair.

What class is the child?” he asked.

“Primary Four,’’ I said and quickly added that my main concern was to have the boy enrolled for the Common Entrance examination.

Dayo did not ask further questions. He called in the proprietor, Segun Olatunji.

Lagos Island is a notorious city where almost anything can be done if one knows the ‘right’ people and has the right amount of money.

Olatunji is the ‘right person’ that gets things done. He said he had been in the business for over 30 years; growing from being a classroom teacher to becoming a principal and now the proprietor of a school. He entered the small office that could barely accommodate the three of us and took a chair at a corner as Dayo retold what I had said to him.

“But why do you want him in Primary Six? Is he too old for primary school already?” Olatunji asked, staring hard at me. I knew that was the right opening to pitch my full cover story.

“The case is complicated,” I started, wearing a subtle frown to depict worry.

I explained to Olatunji that the child in question was my nephew – his mother was dead and his father had abandoned him. The boy stayed with his grandmother and it so happened that my elder sister who lived outside the country wanted our mother to come to join her abroad. Our mother insisted she would not leave the country without the boy; hence, I had been instructed to get the boy’s travel documents; and one of the things he would need was his record of schooling, at least at primary level. Unfortunately, his current school was not government approved; hence the reason to enroll him in another school.

“Okay. I can’t say anything now until I see the boy. Bring him tomorrow because I am not sure a boy in Primary 4 can write a Common Entrance examination. When you bring the boy tomorrow, I will test him to see if he would pass the exam,” he said.

As I made to leave, I asked if his school was government approved, and he answered in the affirmative. I knew there was no way the school, with its chaotic environment, could have been approved by the Lagos State Government. But that lie was a clue I had found for my first subject. I knew there and then that if Olatunji was offered the right amount of money he would compromise any process.

A week later, I took a boy – my supposed nephew – to Olatunji. He asked him random questions about his age, class and school and concluded that he would not pass the examination. Although I had carefully selected a boy who was not very bright academically, it was baffling how Olatunji easily concluded, without any written test, that the boy would perform woefully in the exam.

Olatunji gave a succinct breakdown on how the 10-year-old boy would be “assisted” to pass the Common Entrance examination. He did not mention any tangible academic assistance for the boy. Even when I suggested special tutorial classes, Olatunji was rather dismissive.

“No amount of lessons can help him within the short time,” he had concluded.

He offered to prepare his school’s report for a boy, who in his own assessment is academically poor. He would later suggest to me during a phone conversation that he would get another child to write the examination for my ‘nephew’.

“Let me be sincere with you. I will not allow the boy to go there and write. Another person will sit for him. The person I know is capable will sit for the examination,” he said.

To be sure I understood what Olatunji had just offered, I asked if he was sure my nephew would be well documented.

“Once the form is filled, it will be given to you. And it will show the picture of the boy,” he explained.

After a series of bargaining, Olatunji finally agreed to a lump sum of N120,000. This would cover for the cost of issuing results for the six classes, fixing someone to sit for the examination and a testimonial to certify that the boy, whom Olatunji only saw once, completed primary education.

How Google-generated pictures ended up on Lagos State Common Entrance list

“All we need are two passport photographs of the boy – when he was four and his recent picture,” Dr. Owolabi, the head teacher of Deen Master, told me after explaining that I wanted to enroll my son who was overseas, for Common Entrance examination.

Oluwaseun George Robert, my purported son, was a random picture downloaded from Google, but to Dr. Owolabi and her assistant, Mrs. Alimot Yussuf-Bello, he was my son.

I had told them that Robert lived with my cousin in Canada where he was schooling. I wanted him to apply for a scholarship and part of the requirements was that he needed to have had elementary education in Nigeria. The boy would not be present for the examination, I explained to Dr. Owolabi, who allayed my ‘fears’, reassuring that I had not made a strange request.

“We have helped parents like you before,” he said, with an air of pride.

Dr. Owolabi billed N50,000 for the arrangement, which was paid in three installments because I decided to keep the engagement alive by owing them some money.

Dr. Owolabi billed N50,000 for the arrangement, which was paid in three installments because I decided to keep the engagement alive by owing them some money.

On Saturday, July 28, 2018, when the Lagos State Common Entrance examination was written, Oluwaseun George Robert was on the list of pupils duly registered.

The kid-mercenaries

A 13-year-old Olatunji Samuel had been contracted by his uncle, the proprietor of Honeyville, to impersonate my supposed nephew. It was part of the ‘N120,000 deal.’

Just as the Honeyville proprietor had contracted his own nephew, Fisayo Bello, a boy in the Junior Secondary School section of Deen Master, was also contracted by the school to sit for the entrance examination for my son. These boys understood what they were asked to do. They had been taught to lie about their names if asked.

Certificates for sale

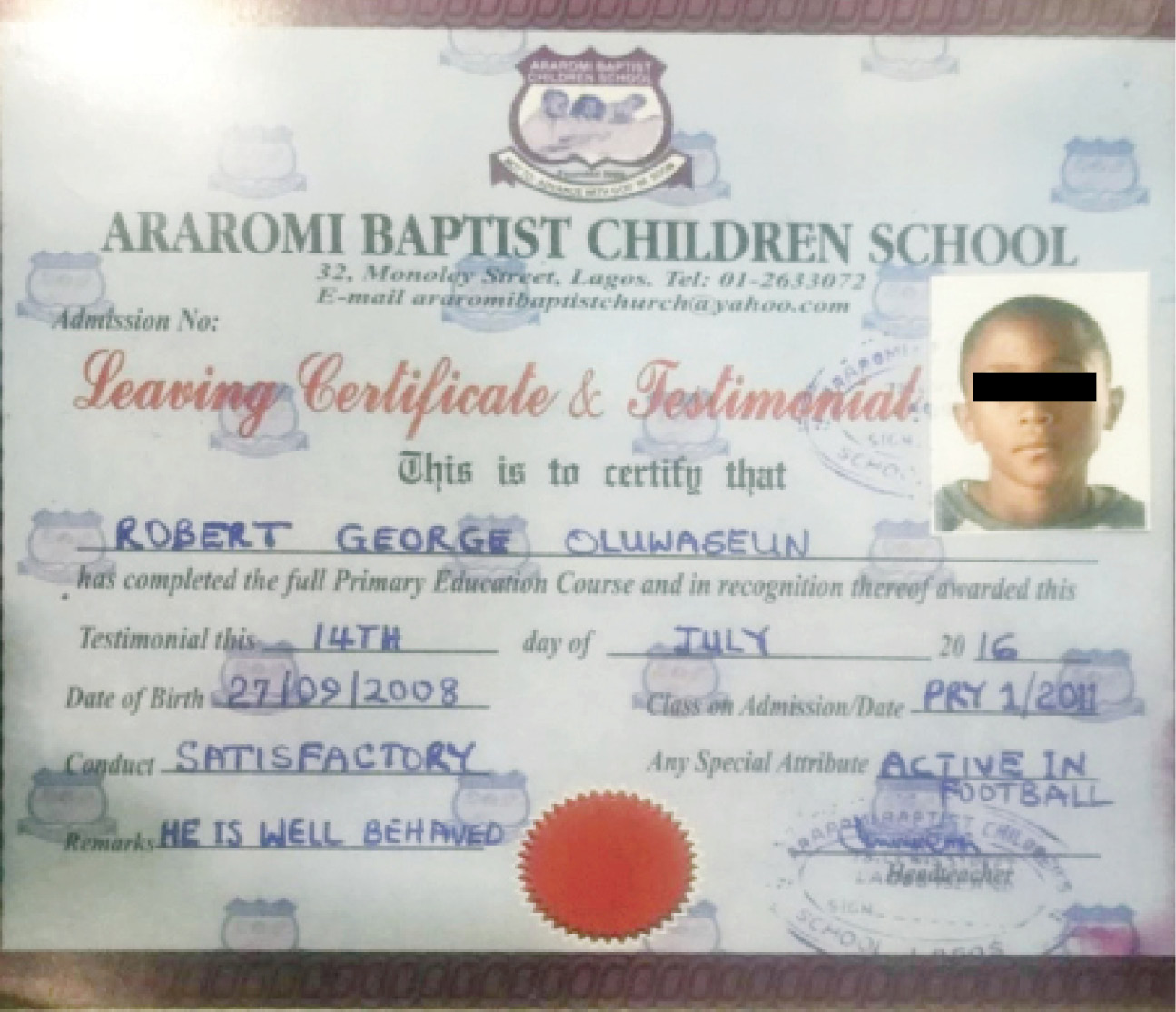

The head teacher of Araromi Baptist Children School, Mrs. Adebisi Oluwaremi, demanded N68,000 in exchange for a certificate.

“Can I pay N50,000?” I haggled.

“It’s a fixed price. In fact, if you want me to issue you teller for the payment, I am ready to do that.

She issued a certificate to a child she never saw. It was the same Google-generated picture I had shown at Deen Master.

Tedious verification process

It is easier to obtain a First School Leaving Certificate (FSLC) from the Lagos State Ministry of Education than to verify one. The process becomes even more tiresome with the attitude of some of the civil servants designated to manage the process.

After about six weeks of back and forth between the Lagos State Ministry of Education and the State Examination Board, I was told to make a payment of N5,000 into the Lagos State Government’s purse for the verification.

I did and brought back the teller, then I was directed to make a photocopy because the Account Department of the Lagos State Examination Board does not have a photocopying machine.

When I came back with the photocopy, the woman who generated the payment slip for me did not allow me to say a word. “Go inside there and wait for me,” she said, and continued chatting with the head of the department.

I had sat for some minutes when the staffer who ordered me to make the photocopy told me to bring the bank teller. I stood across the table to give him the teller I photocopied, but he did not look up. His eyes were fixed on his phone. The woman who had been chatting with her boss in the opposite office came and began to yell at me.

“I told you to sit down there. Sit down there!” she yelled repeatedly.

“It was your colleague that asked me to bring the teller,” I replied. This statement seemed to agitate the workers. The director vowed that I would not get the verification done. He raced down to the verification department, threatening fire and brimstone. Before long, the staffers at the verification department had gathered at the reception. One of them pulled me off the chair and dragged me out, kicking off my bag from the table. This went on in what seemed like eternity. Eventually, I was told the verification was not ready and that I would be contacted later. For six weeks, the civil servants could not determine the authenticity of the certificate.

This was the same certificate I got without sweat. Ajenifuja Kazeem, a staff of the State Universal Basic Education Board (SUBEB), offered it to me without verifying the information I gave to him.

Kazeem was at the reception having a chat with his colleagues during the peak of work hours. “What do you want?” he asked. I explained that I wanted to make enquiry on how to get my First School Leaving Certificate.

“Go to your primary school,” he told me.

“My primary school is no longer there,” I explained.

“It will cost you money then. Why didn’t you get it since you left primary school?” he asked. By this time, he had suspended the conversation with others.

“When I got my own some years ago, I paid N7,000,” he said.

“That’s fine. I don’t mind,” I said, making a gesture to say that money was not the problem.

He put a call through to a colleague, who according to him, helped him secure his own FSLC when he needed it.

Kazeem gave me the phone to speak with this friend. “The certificate will cost you N15,000,” he told me. That was the final price.

I made an initial deposit of N8,000, which was given to Kazeem, with the promise that the certificate would be ready in one week. Interestingly, I received a call from Kazeem three days later, informing me to come and pick up the certificate – same certificate I could not verify in six weeks.

The proprietor of Great Sharon School, who simply gave her name as Mrs. Alayaki, claimed to be a pastor. I told her the same story I had pitched at Honeyville.

She gave the boy I took there an assessment test and concluded that he would need intensive lessons to pass the Common Entrance examination.

“If you enroll the boy with us, I am sure we can groom him well before the examination,” she told me in March 2018 when I first met her.

Great Sharon is a low-cost school in the Agege area of Lagos State. Unlike some of the low-cost schools I visited on the Island, the environment was serene and safe for children.

The boy was eventually enrolled for the Common Entrance examination as an ‘external’ pupil.

“The uniform and the Common Entrance registration is N25,000,” Mrs. Alayaki said.

Two days before the test, I called Mrs. Alayaki to negotiate for ‘assistance’ for the boy in the examination hall.

“It is not possible. I told you from the beginning that it is only God that would make him pass the exam. They don’t allow us stay close to the children. If it is something that is possible, I would let you know.”

Mrs. Alayaki insisted that there was no way the boy could be helped to cheat during the examination, but after what seemed like a long pause that turned out to have lasted only a few seconds, she asked that I call her back in the evening.

I called back at 7pm on Wednesday, July 25.

I called back at 7pm on Wednesday, July 25.

“I don’t know why you are insistent about the boy writing Common Entrance examination. He is not the first person I will process things like that for. The embassy has nothing to do with the class a child is in. What they are interested in is the receipt that the boy is in school, not the Primary Six certificate. That is not their business.’’

I dropped the call, feeling that I finally found an educationist who would not compromise the system for anything. I was, however, slightly disappointed when I received her call after the examination, informing me that my nephew was ‘assisted’ in the hall. But she did not ask for any gratification for the ‘kind gesture.’

Delight Mega School is in a residential apartment at Glover Street, Ebute Meta. Its classrooms are reconstructed with plywood and the head teacher is Mrs. Anu Mercy.

I knew that Mrs. Anu was different when she firmly refused to fabricate continuous assessment results. I had met school owners who did not bat an eyelid before issuing results and certificates to children they had not seen, but this woman could not conceive the idea of fabricating ‘ordinary’ continuous assessment results.

Examination malpractice is an organised crime

This investigation revealed, among many other things, that exam malpractice involves the collaboration of not just the teachers, but school owners and government employees.

Mr. Ike Onyenchere, the chairman of Exams Ethics Marshal Board International, corroborated this as he revealed the sordid details of various examination frauds his organisation unearthed in the course of their supervisory roles.

“Malpractice is no longer the indiscretion of pupils of students. It has become a money-making thing. It has become a syndicated affair where the pupils and students are mere instruments.’’

We’re surprised – Lagos government

When presented with the findings of the investigation, the executive chairman of the Lagos State Universal Basic Education Board (SUBEB), Mr. Sopeyin Ganiyu Oluremi, was surprised that impersonation is possible during the state-organised Common Entrance examination.

He said the state now has the pictures of candidates on their answer booklets in the bid to forestall cases of impersonation during the examination. The undercover children, who sat in for the examination at different centres, also confirmed that there are pictures on the booklets. Unfortunately, despite this precaution, school owners induce government invigilators who aid and abet the act.

This story is sponsored by Tiger Eye of Ghana, funded by MacArthur Foundation.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.