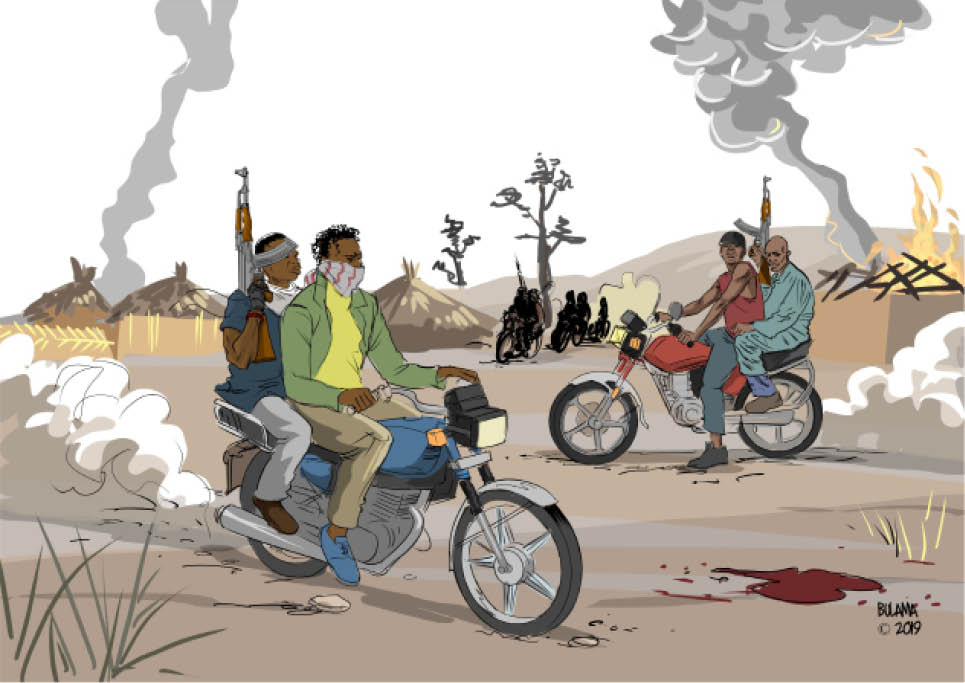

Far more than at any time since the end of Nigeria’s protracted civil war in 1970, the country now faces profound, existential and multifaceted security challenges exemplified by bloodthirsty Boko Haram, banditry, kidnapping and scores of crimes that threaten its existence.

The recent attack on the convoy of Governor Babangana Zulum of Borno state has heightened the debate on insecurity as it has raised the level of conversations and engagement to an apogee.

- Masari meets Buhari over insecurity in North West, North Central

- Governors to meet over insecurity, attack on Zulum

The dastard attack which left two civilian task force men and a policeman wounded has attracted condemnation from all quarters, with the National Assembly leading the pack calling for the removal of service chiefs for efficiency and performance while the Nigeria Governor’s forum alongside civil society organizations continue to echo NASS stands for a rejig of the Nation’s security architecture.

These calls coupled with events that led to them have unfortunately made Nigeria recipe for explosion, making her cumbersome system difficult to relied upon for the security of lives and properties.

But how did Nigeria get to this conflagration while it teetered on the brink of destruction? Where is government ab initio in all of these conversations?

Government everywhere and leaders elsewhere are saddled first and foremost with protection of lives and properties of the citizens. Or what remains of a government which cannot secure its people from marauders and murderers?

This implies that the most essential purpose of government is basically protection of citizens against internal aggression and external insurrection.

Through the menace of dreaded Boko Haram, the country has contends with internal aggression and has continued to battle the monsters for year on end with internally displaced people littered across war ravaged part of the country in numbers.

While insecurity is a global phenomenon, the level at which it disturbs and disrupts the socio-economic, and religious activities in Nigeria called for deep moments of reflection and a change not just in tactics but in methods at which the scourge in being attacked and tackled.

Insecurity like any other existential issues are better solved and resolved using both the technical know-how typified by various security apparatus ranging from the military and the paramilitary to the their funding, equipment — and level of morale and patriotism.

The other is the use of adaptive techniques which have to do with an holistic assessment into the causes and factors that ab initio led to the scourge.

These two pronged approaches have been tested in tackling the dreaded Tamil Tiger in Sri Lanka and of course in flushing the deadly FARC rebels in Colombia.

For Nigeria also to win the war against her existential security challenges, it is time for leaders across board to do more of the work and little of the talk.

Muftau Gbadegesin [email protected]

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.