An African-origin ethnic tribe of about 20,000 people has been living in near total obscurity in India for centuries.

The past few months in India have been mired in controversy due to a string of racist and fatal incidents targeting African immigrants living in the country. But what few Indians know is that Africans and Indians are no strangers to each other: there are at least 20,000 of an African-origin ethnic tribe who have been living in near total obscurity in India for centuries.

Isolated and reclusive, Siddis are mostly confined to small pockets of villages in the Indian states of Karnataka, Maharashtra and Gujarat, and the city of Hyderabad (there’s also a sizable population in Pakistan). Descendants of Bantu people of East Africa, Siddi ancestors were largely brought to India as slaves by Arabs as early as the 7th Century, followed by the Portuguese and the British later on. Others were free people who came to India as merchants, sailors and mercenaries before the Portuguese slave trade went into overdrive. When slavery was abolished in the 18th and 19th Centuries, Siddis fled into the country’s thick jungles, fearing recapture and torture.

These African slaves were originally known as Habshis, which is Persian for Abyssinian (the former name of Ethiopia was Abyssinia). But those who rose through the ranks of royal retinue were honoured with the title Siddi, a possible etymon from the Arabic word for master, sayed/sayyid. It is not entirely clear when the use of the term Habshi declined and Siddi replaced it, but today, Siddi describes all people of African descent in India.

As I journeyed deep into the belt of lush jungles that are part of the Western Ghats, a Unesco world heritage site that runs along India’s western coast, I was excited to delve into an obscure legacy lost in the pages of Indian history. Deeper and deeper we drove on the desolate roads in the remarkable wilderness of the Uttara Kannada district, which is home to hornbills and black panthers, swirling up a trail of dust in our wake. Finally, we arrived at the spartan agricultural village of Gadgera, part of the cluster of Siddi settlements in the state of Karnataka.

From a distance, nothing seemed African about the village or its dwellers. Enthusiastic greetings were exchanged between Pascal, our Siddi guide, and the villagers in Konkani, a local language that’s spoken in a few areas along the west coast. Women were draped in colourful saris and the men looked like farmers from any Indian village. It was a little girl’s braided cornrows that first gave things away. And then, we couldn’t miss the curly hair and facial features that were markedly different from the South Indian people.

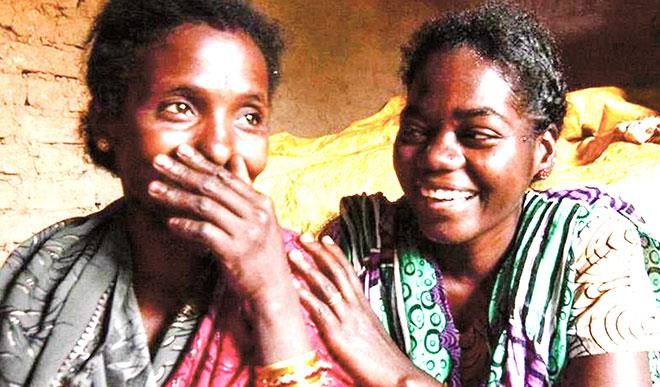

We were invited to an impromptu dance performance. Annie, a slender woman with a bindi on her forehead, and Manjula, a vivacious lady with beaming smile, busted out energetic African moves. The ladies stamped, whirled and twisted their arms to the rhythmic sound of a frenetic drumbeat while the rest of the villagers belted out Konkani folk songs. The excitement was palpable inside the cramped room with a packed audience. In that moment, the ocean between Africa and India had vanished.

Enthusiastic as she was, Manjula then dragged us to a corner to be photographed. Not only did she have the brightest smile, but she also had the most Indian name of all the Siddis we met. The others had exotic and atypical first names like Natal, Celestia, Shobina and Romanchana – quite possibly handed down as a legacy from the Portuguese from whom they fled. Their last names, on the other hand, such as Harnodkar and Kamrekar, are typical of the Konkan region they are now part of.

Although they still look African, Siddis have completely and wonderfully assimilated Indian culture, traditions and language. They are Indian citizens but often the rest of India has a hard time believing they are so.

Years before I met or even heard of Siddis, I had marvelled at the ornate intricacies of tree-of-life latticework carved into the stone windows in Ahmedabad’s iconic Sidi Sayed Mosque built in 1573. The sublime artistry remained etched in my mind – yet I failed to notice the mosque’s name itself: a reference to the Abyssinian Sidi Saiyyed who constructed it.

Regional Influence

The majority of Siddis in India are Sufi Muslims, possibly influenced by the Mughals who were their ancestors’ biggest employers. But Siddis in Karnataka are primarily Catholics, possibly influenced by their Portuguese and Goan masters.

Another time, I was taken by the legend of Murud-Janjira, a unique and unconquered sea fort on an island in the Arabian Sea near Mumbai. I heard all of its glories – except for the fact that it was an Abyssinian minister, Malik Ambar, who constructed it in the 15th Century.

Despite such glaring vestiges, Siddi history has been startlingly erased throughout India. Today, stymied by government indifference and ridicule at the hands of fellow citizens, Siddis lead marginalized lives, while aspiring for a fighting chance at better prospects. Largely working as farmers and manual labourers, Siddis lack sustainable work opportunities. And due to their poverty, education cannot be a top priority either. Sport is one of the few options that can offer them an escape.

In the 1980s, spearheaded by the then sports minister Margaret Alva, the Sports Authority of India started an athletic program for the Africans, whom they saw as medal-winning hopefuls. However, bogged down in administrative failures and secrecy, the ambitious plan crumbled before it could soar high. The collateral, however, was that for the first time ever, Siddis from across the country met, learnt of each other’s existence and their shared ancestry.

While we were there, young boys and girls were playing soccer under the guidance of trainers, part of a joint initiative to uplift Siddi youth through sport by the Oscar Foundation and Skillshare International.

During the game, a very tall man with dreadlocks walked towards us. One of the few Siddis to have broken out of the cycle of poverty, Juje Jackie Harnodkar spoke in a slight drawl and a gentle tone that was a complete mismatch to his athletic build. It was this build and nimbleness that snagged him a spot as an athlete competing for the 400m hurdles in the Sports Authority of India’s doomed scheme. When the programme was shut down in 1993, leaving the Siddi players high and dry, Harnodkar pursued a job with the government.

Today, Harnodkar is working with a small team of 14 young and promising Siddi athletes, to help them get a chance to compete in the 2024 Olympics as part of the shelved plan that seems to have taken new wings nearly three decades later. It’s a promising step in the right direction. Winning a medal could be the revived program’s zenith, coinciding with the culmination of United Nations’ International Decade for People of African Descent (2015-2024). If executed with diligence this time, it could uplift the Siddi community, revive its forgotten history and bring much-awaited acceptance to the Siddi people.

Culled from bbc

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.