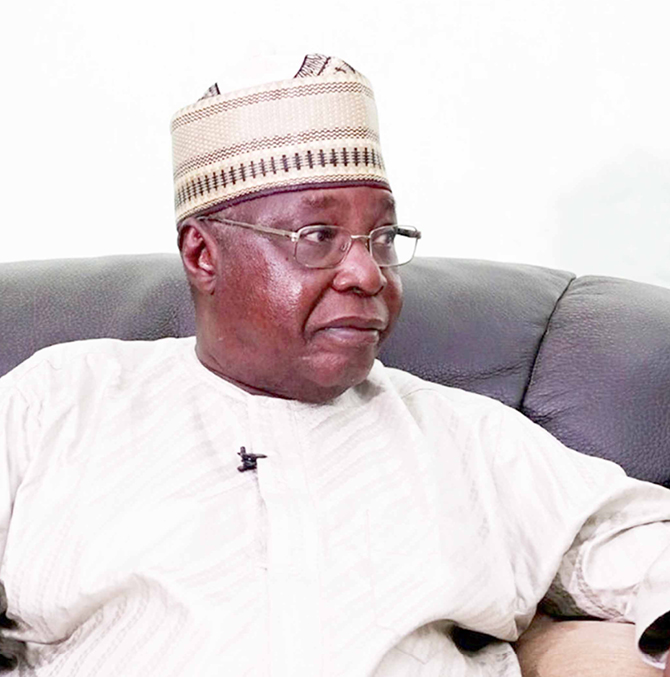

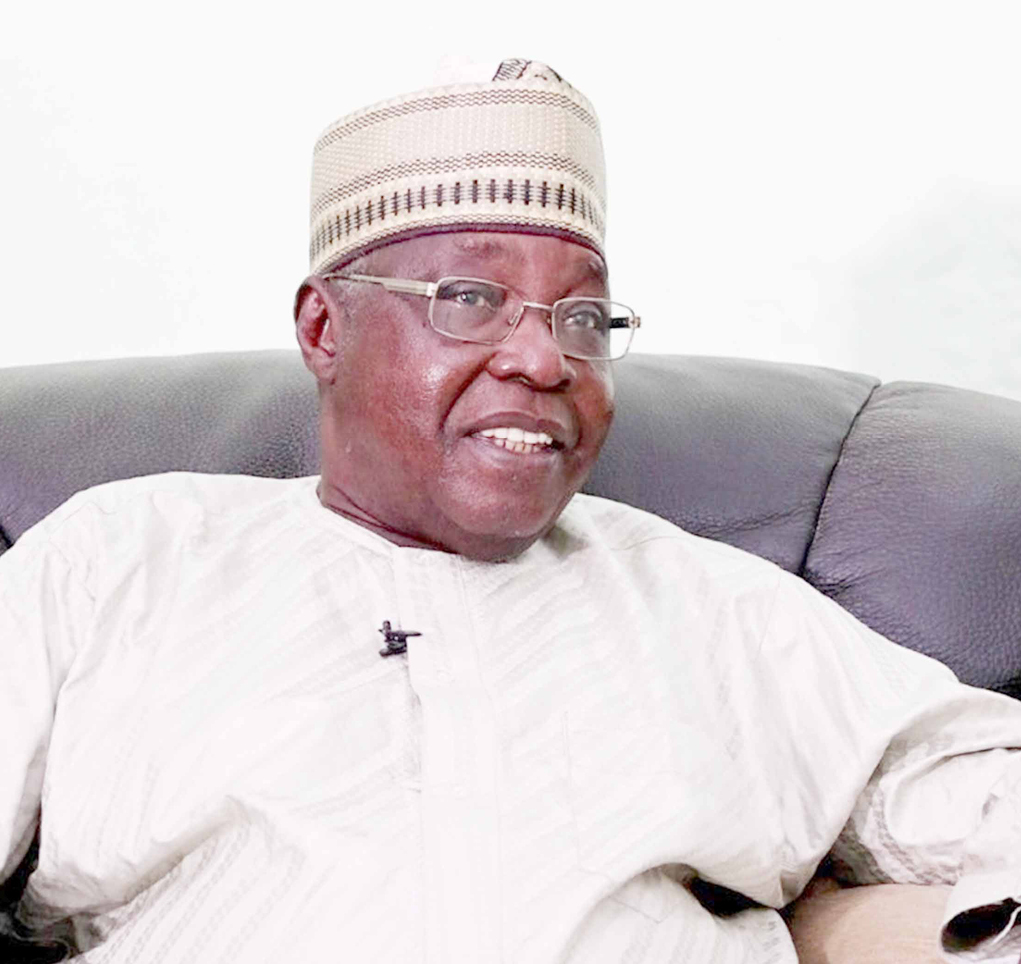

Professor Idris Mohammed is a medical doctor, researcher, lecturer and administrator. The former provost of the School of Medical Sciences in the University of Maiduguri has worked in many hospitals. Also, it is hard to see any committee that has to do with medicine at the national or state level without seeing his name. Prof Mohammed is a winner of the Nigerian National Order of Merit, hence he is one of the elite medical doctors in the country. He is perhaps the only northerner on that list. In this interview, the professor of medicine spoke on his childhood and other experiences.

It seems you were born an academic from childhood, having won a lot of laurels. How were your early school years? Did you have any particular advantage?

I don’t think I had any particular advantage, except that I was born a lucky child. It was even by chance that I managed to be admitted into the junior primary school in Gombe. I had earlier been sent to the nomadic Fulani in the bush to learn Fulfulde; I only came home to see them after a few months.

On my way out of the house one day, I saw two men coming – one Englishman and one Hausa. The Hausa man called me to say something about primary school, explaining that the white man had said I would be admitted into a primary school. That was how my education started.

How 35-year-old land dispute resurfaces, claims lives in Enugu

N/Assembly: Another rubber-stamp talk-shop loading?

So it was not your parents that took you to school?

It wasn’t planned; I was just lucky. From junior primary school, I went to senior primary school, both in Gombe, from where I went to the Provincial Secondary School, Bauchi. After the West African School Certificate, I was admitted into Barewa College for a Higher School Certificate, after which I managed to get admission into the University of Ibadan to read Medicine.

Did you choose Ibadan deliberately or it was the only available university?

At that time, there were only two medical schools in Nigeria – Ibadan, which was established in 1948, and Lagos, established in 1962. Both of them offered me admission in 1964. I went to Ibadan.

How was your experience in Ibadan as a young northerner from Gombe?

Quite honestly, the initial expedience was traumatic. First of all, it was a strange land for us as I had never gone beyond Kaduna and never came across people who were not of the Hausa/Fulani stock, except the minorities around the current Gombe State or Bauchi.

So, going to Ibadan at that time as a northerner was problematic because there was polarisation, although it was not a manifest as it is today.

The most traumatising for me was the first day in the university when we were introduced and one of the professors addressed us at the Trenchard Hall. Among the things he said was that some students from northern Nigeria did not pass any examination but were admitted on the orders of the premier of Northern Nigeria, Sir Ahmadu Bello. He added that some of the students even wanted to read Medicine, and declared, ‘I hope they know we don’t teach medicine in Arabic.’

Only two of us – I and now Prof Audu Ibrahim, who was from Azare – were of the Hausa-Fulani stock. He was so angry that when we came out he said we must publicly protest, but I told him that the best answer to the man, whose name I can’t remember now, was to go ahead and graduate as doctors in the university. So I told him to be patient for five years. That was how he dropped the idea of going to protest and we graduated. And we never repeated any course.

My colleagues treated us nicely. There was trouble in western Nigeria from 1961 to 1966, which led to a declaration of a state of emergency. We were particularly vulnerable and our Yoruba friends advised that we should not go to town without them, and we should not dress like Hausa-Fulani men. They protected us. If they had information that people were coming to attack us, they would come, either to take us away or stay with us. Of course it wasn’t difficult for us to change our dressing code. In any case, we didn’t have many northern Nigerian dresses with us; we usually put on shirts and trousers.

Apart from the two of you reading Medicine, how many other students were from the North?

I think we were 10 or 11. The others were mostly from Kwara in the present day Kogi and Kwara. Ilorin used to be part of the old Kabba Province.

I remember few of them. Some have departed this world. We celebrated our 50th year of graduation a few years ago in Ibadan and had a reunion. We opened a WhatsApp portal where we exchange views.

I think half of us are still alive; three from northern Nigeria – Prof Audu Ibrahim, Prof Albert Anjorin, who is in Ilorin, and myself. I don’t know where others are.

By 1969 you were a brand new medical doctor from Gombe, what happened next?

What happened next was unexpected. I was selected to do my house job in Ibadan, I think out of four of us (northerners) who graduated. Twenty of us graduated that year from the University of Ibadan.

Audu Ibrahim and myself were among the few that they employed in the University College Hospital (UCH).

We graduated in June, and by November there was hajj. At that time I was almost halfway through my house job.

I was selected to be among the medical personnel looking after pilgrims from November to February. I spent three months in Saudi Arabia as one of the only five doctors. There was only one medical team for the whole country, and among that team were only five doctors. I was the most junior because I hadn’t even completed my house job and I hadn’t been fully registered by the Medical and Dental Council. I don’t know how the selection was made, but I was included in the team. That was my first hajj, and I spent three months in Saudi Arabia.

Coming back to Ibadan, there was civil war that did not end till 1970. Soon after I was registered after the house job, I was posted to the warfront. There was no national service then. I was conscripted into the Nigerian Army and given the rank of a field captain and posted to Agbor, near Asaba, where I was the first casualty receiving officer. Imagine a young doctor being sent to the warfront to receive casualties.

But that was in 1970, almost the end of the civil war.

Yes, but I think I went around August. The war did not end till near December.

One of the commanders in Agbor, General Paul Tarfa (rtd), who was a major then, happened to have been my very close friend and classmate although he attended Provincial Secondary School, Yola, while I was in Bauchi. We took our school certificates the same year. And we played hockey for our respective schools. We became friends in 1958. Before I even entered the university we went to Lagos to witness Nigeria’s independence in 1960.

Were you nominated by your respective schools?

Yes. I was nominated from Bauchi while he was nominated from Yola. And by chance, we met in Kaduna. We were the smallest in the contingent from northern Nigeria going to Lagos, so we naturally stayed together.

He is now the chairman of the North East Development Commission.

After the war, what was your first civilian job?

After my house job, I was appointed a senior house officer at the UCH. After that, they gave me an appointment as a registrar.

In the first six months, my boss, Prof Akinkugbe who died over a year and half ago, called me to ask if I would like to go to the United Kingdom to specialise; and I said yes.

One month later, he called me to say he had found me an appointment as a clinical assistant to Prof Mitchel in Nottingham and he said I could report within one month. I had to find sponsors because he only found me the appointment.

But by the grace of the Almighty Allah, I don’t know how I got myself to the Government House in Ibadan, and Musa Usman, who was the military governor of the North East at that time, happened to be there. Someone introduced me as coming from Gombe and he called me to say that I should go and pack my things and follow him to Maiduguri. But I told him that I had a contract appointment and could not go without permission. He said I would go with him, permission or not.

He was actually very excited and never let me off. But I didn’t follow him the next day, I had to find permission. So, I went to Maiduguri with permission. As soon as I got there, he got me appointed as a medical officer grade 2, with a promise that I would immediately be sponsored to go abroad.

I told him that I had already gotten a place to go and only sponsorship was outstanding.

I don’t know who he exactly spoke to in the Civil Service Commission, but I was an officer of the state government, so I was given sponsorship, not scholarship. I went with my salary for the initial two years. It was like in-service training where the Crown agents in London were paying my salaries. It was 56 pounds per month, which was quite adequate in those days.

Were you in the UK with your family or you were still a single young man?

I went as a single person, but after few years, I think it was in my third year, I received a letter from the late Isah Kaita, the then minister of education in the North, to the effect that my wife, whose photograph was included in the letter, was coming to London on a particular date and I should got to Heathrow Airport and receive her.

I had never known her before. I don’t know who gave them the impression that I was going to marry an English woman, which I was never going to do because I never fancied them.

And I was not expecting a wife because I wanted to finish all my postgraduate studies. I finished from Nottingham in two years, but before I left, my professor asked what I was going to do after and I said I would go back home. He asked if I would not study other disciplines that would help me practice medicine better before going back home. I asked for suggestions and he said it could be something that would help me in infectious diseases.

I said I had always wanted to do immunology but there was no opportunity of getting a place. He asked if I truly wanted to do immunology and I said yes.

Within two weeks, he said he had found me an appointment as a medical research fellow in immunology in the UK Medical Research Council.

I registered for a PhD but through a research programme, which was mostly clinical and laboratory, but mostly laboratory but of patients with rheumatic disorder, where immunological phenomenal played an important role.

By the time I had done one and half years, the boss said I had gathered enough data for two postgraduate theses. So, without consulting him I decided I was going to do a MD, which I would submit to the University of Ibadan, then PhD, which I had already registered for and I had already been awarded the mPhil.

When I wrote the first chapter of my thesis, I didn’t state that it was for MD. I just gave it to him and said it was an introduction to my thesis. He sat on it for two months.

When I asked the secretary, she said he hadn’t even opened it. I just kept quiet and went on with the rest of the chapters and produced the complete thesis, which I printed and handed to the University of Ibadan after informing them that I would like to submit my MD. The process then was very simple. You would apply that you wanted to do an MD and you were doing a research.

Is it like a PhD in medicine?

Yes, but PhD was clinically biased towards special care. That was how I got my Doctor of Medicine degree by research from the University of Ibadan.

But there were problems with that MD, although there were some surprising things. I flew from England; and the following day, after I arrived in Ibadan I went to see one Prof Adeniyi, whom I served under as a house officer before I went abroad. I just went to say hello to him. I was just in the middle of a discussion with him when I heard somebody who came from behind and asked why he wasted his time to come to Ibadan to examine this thesis. He said the thesis did not need to be defended as it was very good.

Adeniyi told him that the candidate was there listening to him. When he saw me, I didn’t know he was going to be the external examiner from London. He was a professor of immunology from the University of London and one of the most difficult examiners. My predecessor in the Medical Research Council had to rewrite his thesis two times before this external examiner passed him.

So, they sent me away. Another drama happened the following morning when I went in for the examination and the head of the department introduced the three examiners – two internal examiners and the white man from London.

The first question I was asked was by an immunologist at the University of Ibadan. He was angry that throughout the thesis I did not quote a paper written by one lady who was the wife of the late Prof Tam David West.

He asked if I had not heard of the work of this doctor from the University of Ibadan on the subject and I said I had heard. He asked why I didn’t quote her. I brought out my books of references and said I didn’t quote her because I had made too many references on the subject and wanted to include only five, and her own was not among the best five. I brought the reference out from my box and the external examiner took it and gave to him.

He said I should just go out and tell the secretary to type it on a piece of paper, cut it and paste below; which I did.

As soon as I came and resubmitted, the external examiner stood up and stretched his hands and congratulated me. Nobody asked me any other question.

So the defence of the thesis that should have taken three to four hours was completed in five minutes.

After I returned through the departmental office to go out, there was pandemonium because they were wondering what happened. They wondered why I was dismissed so early. Was the thesis rejected before it was defended?

I went away and later received a letter to the effect that the defence was successful.

It was a pleasant surprise to everybody in the University of Ibadan that somebody had defended an MD thesis in five minutes.

Let’s go back to the question about your family. Did you go to Heathrow to receive your wife; and what happened?

I went to Heathrow to receive her but they wouldn’t let her out until they saw me. And there was no way I would have been allowed to go to the arrival – the immigration area—without going through departure. So they refused to allow me in.

In the end, after they had waited for nearly one hour and didn’t see me, they had to send one of them to the arrival area to announce that one Dr Idris Mohammed was required at the information desk. When I got there, he accompanied me to the immigration officer holding my wife at the time. That was how she was allowed to come in with me and we drove to Nottingham.

Were you seeing her for the first time?

Yes.

Who arranged the marriage?

Well, my friends arranged it, including a former bursar of the Ahmadu Bello University, Dr Hamza Zayyad, who facilitated my early departure from Nigeria to the UK. As bursar he got the ABU to take responsibility for my transportation and the first few months of my salary before the ones of Maiduguri started coming in.

He was the principal person. Then the late Dauda Birma, a onetime minister of education and my classmate, paid the dowry in Kaduna.

Was it not arranged in Gombe?

It was in Kaduna because she was the stepdaughter of Isa Kaita.

When you came back to Nigeria, were you committed to continue in Maiduguri, where you were recruited?

By that time, the North East had been broken into three: Borno, Gongola and Bauchi, so I reported to Bauchi, having hailed from Gombe, which was part of Bauchi State at that time. I reported to the Bauchi State Civil Service Commission in fulfillment of my promise to return home and serve before leaving for the academia.

I was posted to the state Ministry of Health, where I continued my appointment as a medical officer on grade 2 despite three additional qualifications I obtained from the UK—Member of the Royal College of Physicians, Doctor of Medicine, Diploma in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.

Despite those additional qualifications and three years after my appointment as a medical officer on grade 2, I continued on a grade level 8 salary for nearly a year before my appointment was reviewed to chief medical officer, grade level 15, with arrears.

From 8 to 15, that was almost double, how did you feel?

They took cognizance of my clinical research work in the UK. That’s the advantage of MD over a PhD. If it was just pure PhD it would have been simply research work without any direct connection with patients. But I was looking after patients and conducting research on them at the same time. So, I was practising. That was the advantage.

Also, in Nottingham before I became a member of the Royal College of Physicians, it was a clearly clinical training before I went to do the research work in the Medical Research Council, Immunology Unit.

They took that into cognizance and added the five years I spent in the UK, and the additional qualifications to determine what I should have been. I was appointed to take over from one Indian, Dr Sojid, who was extremely nice and friendly with me. He decided to retire voluntarily.

You eventually became a permanent secretary in the Ministry of Health, how did that come about?

I was promoted to the position of a chief medical officer in 1978, but in 1979, after the civilian government came in, the governor, Alhaji Tatari Ali, called me one day to say he was going to make me a permanent secretary the following day; just like that.

I thanked him but said I would not take oath of allegiance until he sent me for training in administrative and financial management. All the people there were exceedingly surprised.

Later on, I got to hear rumours around Bauchi that one silly man was offered the job of a permanent secretary but he said he would not take it until he was sent for further training.

Tatari Ali laughed along with others and said he would send me for training in administrative and financial management but I would first of all take the oath the following day.

He fulfilled his promise by sending me to the Centre for Management Development in Cambridge, where, along with some other Nigerians, we undertook training in Financial and Administrative Management, a certificate course.

At what point did you leave the civil service and returned to the academia?

I had told Governor Ali that I returned to Bauchi to serve for three years, unlike some people who refused to return to their states. So, I went straight to the academia. I had promised myself that I would at least serve the state government for three years before transferring to the ABU, being the only medical school in the North.

Ali understood it very well and we processed my request through the secretary to the government and he approved it and forwarded to the Civil Service Commission. But the commission refused to approve it, saying that I was trained at the public expense and had spent only three years. They said they would not release me until I spent another two years.

But the governor called me to say that I should not mind them, adding that they did not know that the constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria vested power on him regarding all these approvals. He said I should ignore them and go to the ABU.

So, I went, but it was not until 12 months before the transfer certificate came.

So, you preferred the job of a lecturer to that of a permanent secretary?

Oh yes. People thought it was surprising but I did not think so, although I had lost three years of academic promotion. My colleagues who returned immediately after post graduation training, not necessarily in medicine, were promoted after three years.

I applied to transfer my service to ABU based on my publications. They offered me the post of a reader, subject to external assessment.

I learnt that people in the academic and promotions committee, particularly, the late Dr Yusuf Bala Usman and Prof Abu, who were in the appointment and promotions committee, protested, saying I should have been appointed a professor straightaway based on my publications. They said there were people with six publications or less being promoted as professors while I had 16.

In their wisdom, the appointment and promotions committee settled for what they offered me. Many people expected that I would not accept it, but I did.

But a reader is like an associate professor, right?

Yes; but the ABU did not accept the term, associate professor. And I didn’t mind. I got to the ABU as a reader on grade level 15, pending assessment. So I assumed duty on grade level 12 or 14, which is four years below a permanent secretary.

That is demotion.

Yes. A week after I assumed duty, one Prof F.B Attah, who was the Head of the Department of Pathology, came to my office to say he wanted to see the man who abandoned the post of a permanent secretary to take a job on level 13, leaving all the perks of civil service for the impoverished climate of the academia.

I said I didn’t consider it anything because my interest was paramount over financial gains.

But mercifully, my external assessment only took three months, so I was on grade level 13 for only three months and I was promoted. I was also paid up to grade level 15.

I was due for promotion the next year based on my publications, but there were two of us. And there was only one vacancy in the department.

The head of department called me and appealed to me to drop my ambition of becoming a professor because he was sure that if he forwarded the two names, the appointment and promotions committee would pick me and leave the other person. I said there was no problem.

So you had to wait?

I waited.

But you didn’t stay too long in the ABU before moving to the University of Maiduguri, why?

When I joined the ABU there was no medical school in Maiduguri. However, by 1976, seven new medical schools were established by the National University Commission, of which Maiduguri was one, but it was not yet functional.

Professor Jubril Aminu, who was appointed the vice chancellor, came to the ABU to interact with the vice chancellor at the time, Prof Ango Abdullahi, to beg him to release me on secondment for two years.

Did he know about you from Ibadan because he was another alumni?

I met him in Ibadan, but he was four years ahead of me. He also did his house job in Ibadan, from where he went to the UK and I followed suit.

Ango Abdullahi told him that he had just lost his dean of the Faculty of Medicine and I was the deputy, so he didn’t feel comfortable to let me go.

But Prof Aminu argued that the ABU had other professors of medicine, along with other grades of academic people in the Faculty of Medicine, whereas in the University of Maiduguri, there was not a single Nigerian professor of medicine, and the NUC was insisting that there should be a professor in every department; in fact, preferably, two.

They were prepared to give full accreditation to the College of Medical Sciences in the University of Maiduguri.

Prof Aminu also appealed to me personally, but I had my own reservations. I didn’t want to go to Maiduguri, but I felt it was a responsible thing to respond to his request, especially if it was going to be for only two years.

Fortunately or unfortunately, after one year I received a letter from the Federal Ministry of Health that the Head of State would like to appoint me the chief medical director of the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital. I couldn’t say no. The letter was signed by the then permanent secretary, Dahiru Mohammed, who was later governor of Bauchi State.

I replied that I was willing to accept it, but Prof Aminu was most unhappy. So, since I was not leaving Maiduguri, he gave me a condition that I should continue to attend Senate and teach.

I was appointed along with 11 others in August 1985. I was the foundation chief medical director/chief executive.

Unlike Prof Aminu, you did not make it to the position of a vice chancellor despite other positions you held, what happened?

I think it was the will of the Almighty Allah.

You completed your tenure as the provost of a medical college around 1999, what have you been doing since then?

After my tenure, I was given one year sabbatical leave. At that time, the late military head of state, Sani Abacha, had established the National Programme on Immunisation, where Prof Umaru Shehu was the chairman. I went to him to say that I would like to spend my sabbatical in the agency because of my background and training and to help them establish immunisation on a firm basis.

So, in 1999 I moved to Abuja to serve. They appointed me a consultant to the National Programme on Immunisation and I decided my work plan.

Did you retire from that job or you just left?

I served four years, up to 2004 and didn’t want to continue, for personal reasons.

You have been in many committees and won awards, which one of them are you mostly proud of? Which one brought more money to you?

Well, one award brought N1 million.

The Nigerian National Order of Merit; just N1m?

Yes. But they have raised it to N10m or N20m.

It is the highest award for academic and professional performance. I think the most appreciated by me is the inclusion in the University of Ibadan College of Medicine Wall of Laureates and Fellows. There were only 14 of us. I appreciate that as the highest.

It seems you are the only northerner in that list, is that correct?

The list shows me as the only northerner. Before that one, of course I was a fellow of the Nigerian Academy of Science. I am also a member of the Nigeria Academy of Medicine and the Nigeria Academy of Medicine Specialties, introduced in the last three years.

I have also been a Fellow of the Royal Society of Medicine since the 1980s; and more recently, about four years ago, they made me a live fellow of the Royal Society of Medicine.

Apart from those societies, I am a member of professional associations, including the British Medical Association, British Society of Immunology and their Nigerian counterpart.

At your age, do these associations really keep you busy?

As busy as you want to be. I don’t respond to many invitations if they involve travelling. This is because it is difficult to travel from Gombe to anywhere, even Bauchi. That has restricted my activities.

And that is to the benefit of Gombe State because I was appointed the pro-chancellor and chairman of the Governing Council of their university.

And we established a college of medicine, which has now graduated three sets successfully. In fact, I believe that this week, the Medical and Dental Council would visit Gombe for re-accreditation. This time they hope to get full accreditation.

After establishing the College of Medical Sciences, by the time they were to come for clinical training we needed a teaching hospital. There was a purpose-built federal medical centre, in fact, the only one in Nigeria. It was built by the Africa Development Bank to the standard of any teaching hospital. So we appealed to the Federal Ministry of Health to turn it into a teaching hospital so that students of Gombe State University would be trained there; and the president approved it. So the Federal Teaching Hospital in Gombe and the Gombe State University have been benefiting.

When I retired to Gombe, I offered to provide free clinical services to the Federal Medical Centre, but in their wisdom, the board decided to give me an appointment to make my activities in the hospital legal.

They appointed me as an honourary consultant physician and decided on a monthly stipend, which they have been paying up till now.

Do you really go to the hospital?

I do my weekly ward-round twice any time I am in Gombe. And now, of course there are clinical students I give lectures in the hospital. So I am supposed to be in the hospital everyday.

At 81, do you still have the time and energy for those activities?

I do, despite a bathroom accident I had in Saudi Arabia. Luckily, it doesn’t stop me from standing or walking, the only thing is that I cannot walk 3 miles without stopping three times.

How do you spend your typical day?

I manage to visit one or two people.

As the Dan Isa Gombe, do you have any particular role in the community or palace?

Not really, although theoretically, the emir can give you any assignment. But these days there are not so many assignments going on.

Assignments within Gombe town are mostly undertaken by the Yerima Gombe, who is the district head. He deputizes for the emir most of the time. He is the uncle of the emir, but he refused to contest for the post of emir when his elder brother, Sa’adu Abubakar died. He said he could not compete with his children to become emir, a decision that most people appreciated.

How is family life?

Not bad. The girls are married and the boys have graduated and taken up jobs. Two of them are undergoing training here.

One of the boys is in Baze University while the other is in Nile University doing Architecture and Civil Engineering respectively. So my family life is fine.

Do you feel neglected by the government or you are satisfied with the way they consult and seek your input on policies?

Not really. As I said, being confined to Gombe State means that when you talk about government engaging me, you are talking about the state government, And in fact, they over engage me.

Do you have hobbies? I saw something about snooker; what do you do in your private time?

That was a long time ago in Ibadan and the UK. I played snooker a lot.

So you don’t do those things anymore?

No. In any case, snooker tables are not available where I am. And there was none in Maiduguri while I was there.

However, I have seen some adults improvising tables and using sticks and balls to do snooker.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.