Reviewer: Omotola Otubela

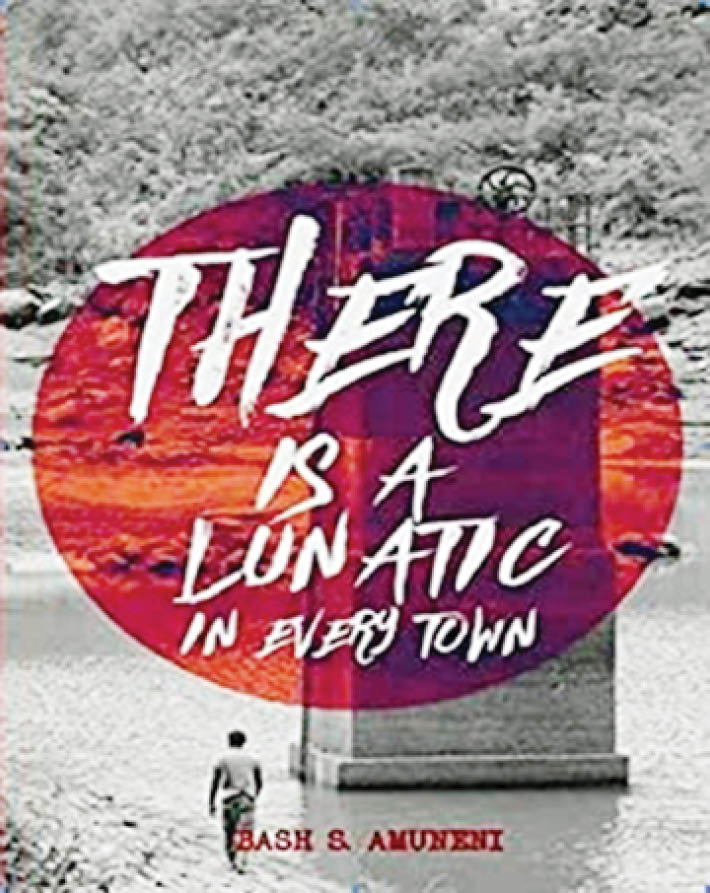

Book: There Is a Lunatic in Every Town

Author: Bash Amuneni

Publisher: SEVHAGE Publishers

Number of pages: 83

Ideas become irrelevant when they are not channelled or directed to the right people through an effective medium. African poets such as Wole Soyinka, John Pepper Clark and Tade Ipadeola have called attention to the relevance of African literature. A new voice joining the chorus of these legends is the performance poet and essayist, Bash Amuneni. His works include Freedom, a spoken word poetry album released in 2015, and ‘There Is a Lunatic in Every Town,’ published in 2016. From a close study of these two works, one can observe that Amuneni is a poet that is greatly inspired by the society at large.

‘There Is a Lunatic in Every Town’ significantly encompasses real-life happenings. The collection is divided into three sections: ‘Resonance’, ‘Intimacy’, and ‘The Human Condition’, consisting of 17, 10, and 18 poems respectively. The collection posits that people are the architects of their own destruction. According to the poet, we are all lunatics dressed up in fancy clothes, pretending to be dealing with life our own way. We all are lunatics because we contribute to the increase of social vices in our environments, knowingly or unknowingly. We all are lunatics because we choose to stay quiet rather than do something to improve our political or economic situations. This silence upsets our psychological balance. Amuneni writes:

I saw her

but what I didn’t see

was our consciences give

just highway [kings]

who really cares

for the beggar mum

her infant and their

vacuum.

The opening poem, ‘We Would Continue the Conversation’, is quite disturbing, as it evokes the imagery of unrest and a situation where pain overshadows pleasure and peace of mind:

Where fleeting discomfort

Outweighs the soft stroke of a patient wind.

Also:

[A]nd hurt can be traced

in honest batting of eyelids

carving a broken trail of tears.

Other poems in the first section such as ‘Yesterday in Aba’, ‘Ileyi’s’, ‘Something Happened in Nyanya’, as well as ‘Flinch’ – a poem dedicated to the Chibok girls – all follow this disheartening and sorrowful path. In ‘Something Happened in Nyanya’, the poet writes:

I heard a blast and dawn’s façade was torn scarred in hot tears of gash and guts pelted flesh smacked in disgust at shattered panes.

In the midst of all the chaos, the poet reminisces on the good old days, informing the reader that things used to be rosy and peaceful before greed set into the hearts of people and political officeholders became shamelessly polluted and corrupt.

In ‘Ghali’, Amuneni writes:

Remember the times before the rustling of harmattan and candid rain when children would dance sticky mud between naked [feet]

Sadly:

[L]ife surprises at noon boasting in reprise of uncertainties carrying its canny and callous ways.

In ‘My Mother’s Compound’, the poet reminisces on homecoming:

I have come home

Where we bragged over

morsels of pounded yam

and chunks of skewed meat

in a pot of a tasty [mix]

The second section, ‘Intimacy’, offers poems that liken love and affection to the beauty and essence of nature. In ‘Chlorophyll’, the poet limns:

Amber strips

sated of colour

fresh [chlorophyll]

He continues:

Love does not journey to the moon and back

It cuddles

secure in a heart

caged

in the simple warmth of your trust.

However, it is not only the issues treated that place Amuneni in the league of the likes of Wole Soyinka, John Pepper Clark, Dike Chukwumerije and Efe Paul Azino. His use of language, style, and technique, combined with his thematic essence to earn him such repute. He blends a few African languages with the English language in poems such as ‘Akwanga’:

I taste her in longings of Samiya

from a freshly etched kwarya

Mutun’s masterpiece

returns in generous submissions

Sauka Lafia

Also:

Akwanga warms at Akuriwari

She gushes at Hunku

She is wild at Gizar

Kwararafa’s ageless maiden

Akwanga is coming

Now!

Again in ‘I Drank from the Benue River’:

[N]uance of a buzzing kakaaki

charms to contemplate this distinct strips of anger

bathed in genger

soft and calling [nyam-igyo]

Not only does the poet go beyond the norm of using literary forms to illumine the day-to-day events and experiences of Africans in their habitats, he uses his poetry collection to reveal the psychological and emotional struggle that the human mind, in general, suffers from. This feature of the collection is most evident in the poems of the final section, ‘The Human Condition’. ‘Lunatics on the Loose’ sets the pace:

There is a lunatic in every town

building hospitals, they never use

gathering bills for pills

He continues:

[S]canning huge garbage heaps

by the roadside every time

yet doing nothing each time

passing by, tossing a little more to build up a pile.

As opposed to the idea that ‘lunatic’ here would refer to a mentally unhealthy or deranged person, the poems show different angles from which one’s behaviour or misguided idiosyncrasy qualifies as lunacy and includes such a person in the rank of ‘lunatics’. This set of people suggestively includes those in positions of power, as well as the common person on the street.

In addition to adopting a very unique style of writing, Amuneni wraps this literary work in a wide range of figures of speech, making undeniably tasty morsels. This adds aesthetic value to the collection.

In the heat rising from treating sensitive and serious issues, the poet introduces a delightful and funny poem titled ‘Isi Ewu’, named after a Nigerian delicacy otherwise known as goat head pepper soup. Even though the isi ewu makes the poet-persona stool uncontrollably, he still craves more and vows to consume it to his heart’s content:

Isi ewu

I don’t care

Let’s bet, I swear

I would do you hot yet [again]

By introducing this lighthearted poem, one may infer that the poet is trying to tone down the disheartening element of the principal poems. More than this though, ‘Isi Ewu’ creates a distraction from the serious issues realised by other poems, thus causing a bump in the entire poetic rendition.

The collection is marred by some grammatical inconsistencies. For instance, in ‘Mirror’, the poet-persona ends the stanza thus:

[A]nd loop the world to heed

the chilling chatter

beyond this [sic] cracked walls

In the last line of the stanza above, the poet persona uses the singular determiner ‘this’ in referring to the plural noun ‘walls’. One cannot shelter this grammatical infelicity under the umbrella of poetic license.

The poet uses this collection to show that humans, their minds and the society in which they reside are all intertwined. This means that human actions and inactions are influenced by their minds and also reflect the societies they live in. Inasmuch as humans are products of their societies, a defect in any of the three areas will affect the others. In ‘Haze’, the poet writes:

Of gaping hoofs trudging rugged streets

in patched flip flops

chasing a sale

Of sweat for sweet

on these mean streets

that eat dreams

Of deals brokered

at the edge of grey [kerbs]

By treating all these important themes in relation to the African society, the African, human life and living conditions in general, Amuneni’s There Is a Lunatic in Every Town becomes a huge contribution to the narrative of the African experience and the enlistment of African literature amongst the world’s literature. This collection is highly recommended for academic engagement as well as leisure reading.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.