by Iyadunni Olubode

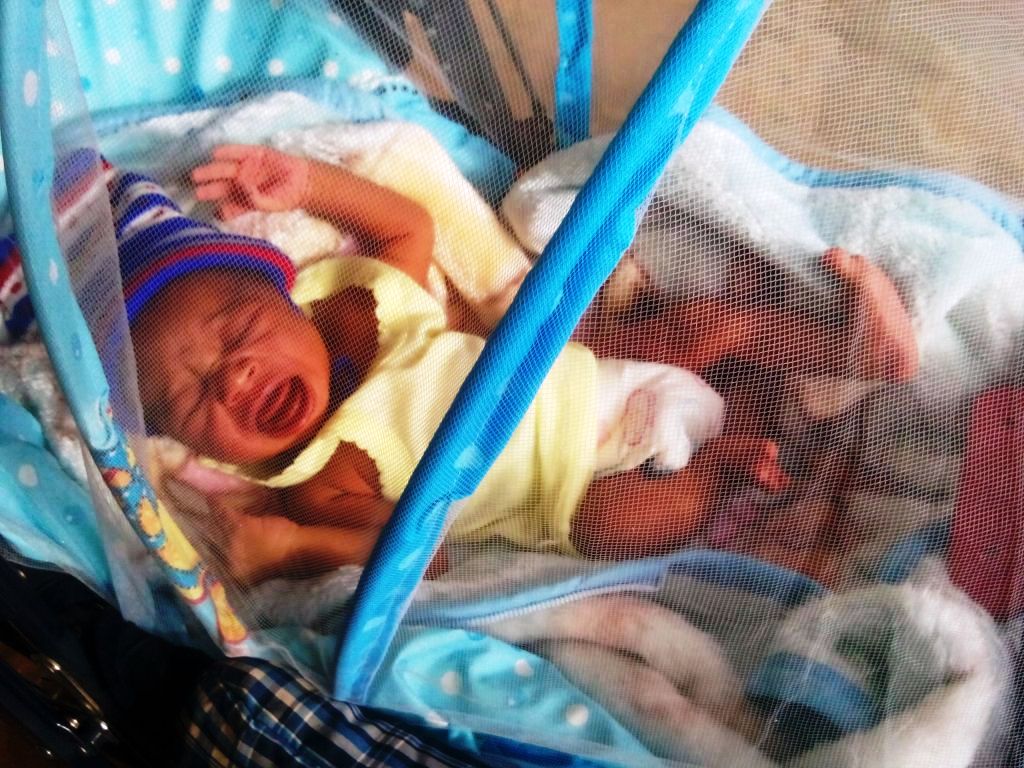

The #GivingBirthinNigeria campaign is elevating the issues around maternal mortality in Nigeria in order to put a human face to the issues that have led to death of mothers and children.

According to UNFPA, in 2017, 67,000 women died from pregnancy or childbirth-related causes in Nigeria, the highest number of maternal deaths compared to any other country in the world, and about a quarter of the global total.

One of the biggest issues is that barely 40% of all women in Nigeria give birth in health facilities with the assistance of a skilled birth attendant, a factor that significantly decreases their risks of a poor outcome.

Nigeria’s health care system faces significant challenges, like many other countries in Africa. Issues include quality of service delivery, poor attitudes of health care staff toward their patients, lack of expertise, inadequate equipment, shortages in essential medicines and an unstable supply of power and clean water. All of these issues will have to be addressed to improve maternal health care.

The #GivingBirthinNigeria campaign was launched in early 2019 as an effort to better understand the key drivers of maternal mortality at the community level and catalyze accountability for these deaths with new data and insights. Over the past 18 months, this campaign has helped create a sense of urgency in the country, the kind of “positive anger” we need to spur action toward solutions.

The consortium in this effort, Africare, EpiAFRIC and Nigeria Health Watch, conducted the maternal death review from May 2019 through May 2020 with funding support from MSD for Mothers, and was carried in 18 communities across six states, each representing a geopolitical zone (Bauchi in the North East, Bayelsa in the South South, Ebonyi in the South East, Kebbi in the North West, Lagos in the Southwest and Niger in North Central). The teams interviewed women, men, youth, traditional and religious leaders, health workers and others.

From these accounts and their related research, the teams draw a number of useful insights and recommendations, detailed in a new report.

In particular, the report highlights the need to:

- Take a bottom-up approach. Though the leading direct causes of maternal deaths are essentially the same across all localities and regions of the country, there are different underlying causes and factors that affect women’s health-seeking behaviors and contribute to their health outcomes, the teams found. Due to prevailing cultural and religious attitudes, a woman in Ebonyi State is more likely to entrust her delivery to an unskilled birth attendant than to go to the nearby primary health care. In Niger and Kebbi States, functioning health facilities are few and far between and not easily accessible, giving most women little choice but to give birth at home. For those that do have access to a health facility, in some northern states their husbands are resistant to them receiving care from a male health care worker. Overcoming these barriers will take community-based approaches, developed and implemented with buy-in from religious leaders, traditional rulers and other community leaders

- Enlist the help of traditional birth attendants (TBAs) in effecting positive change. Many women in Nigeria turn to TBAs, traditional healers, herbalists and “massagers” for support and services during pregnancy and childbirth. The national government can help by establishing guidelines for TBAs and other unskilled birth attendants. States can help by enforcing those guidelines and otherwise regulating their activities.

- Ensure that all 774 local government areas (LGAs) have a functioning primary healthcare center (PHC) that is well-equipped to provide maternity care services. Every woman must be within reasonable distance from a functioning PHC, with no prohibitively long and arduous journey required. This is a matter of states identifying local needs — with local input — and leading efforts to revitalise PHCs that are in disrepair or otherwise non-functional.

- Eliminate affordability as a factor in whether women seek facility care. A major barrier to women seeking facility-based care during pregnancy and childbirth is cost. Nigeria has the highest out-of-pocket health spending at more than 70%. Health insurance schemes, while they exist, have not been fully implemented across states and coverage is extremely low, nationwide only 3% of women aged between 15 and 49 have health insurance. In addition, these schemes do not include comprehensive provision of maternal health services. The delayed implementation of the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF) has meant that the basic package of services, which includes free maternal care for all mothers in rural areas is not being delivered.

- Address the chronic shortage of health workers. Training community health workers to provide basic maternity care services can help make up for the dearth of skilled maternity care providers in under-served areas. Poor treatment by overworked staff is often cited by women as a reason they avoid going to health facilities to give birth, investigators found. State governments should collaborate with professional associations (e.g., Nigerian Medical Association, National Association of Nigeria Nurses and Midwives) to ensure that practitioners are available in every LGA, are adequately remunerated and are protected.

- Expand maternal death and perinatal surveillance and response (MPDSR) activities to communities so that every death is counted and investigated. All maternal deaths must be fully investigated and understood to inform improvement measures and policies. This requires putting in place a multi-step, systematic process that is community-owned and executed, and includes an in-person visit with the family to get the full story behind the woman’s death. The Why Women Are Dying in Nigeria report recommends that the federal government, through the Ministry of Health, work with state governments, local governments and ward councils to facilitate this community MPDSR process; that every state has a functioning and fully-funded MPDSR steering committee and that surveillance teams can easily submit their data as part of a nationally integrated health information system so that learnings lead to better quality maternity care.

Our country’s future prosperity depends upon us winning that fight top stem the levels of maternal mortality. It is time for Nigeria’s maternal health community to deliver on its commitment to changing what it means to give birth in Nigeria.

Iyadunni Olubode, Nigeria Director, MSD for Mothers

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.