On October 24, 2019, an Ikeja Sexual Offences and Domestic Violence Court in Lagos State sentenced Adegboyega Adenekan, a school supervisor, to 60 years imprisonment for defiling a two-year-old pupil.

In convicting the 47-year-old, the trial judge, Justice Sybil Nwaka held that “The victim, in her evidence before the court, said Adenekan put his mouth and his hand in her wee-wee (private parts). She also said that the supervisor put his mouth in the private parts of her best friend (name withheld).

“The little girl said Adenekan covered her mouth when she attempted to shout and that he defiled her twice on the school premises; at his office and at the hallway.

“This defendant (Adenekan) is conscienceless, wicked, an animal and not fit to walk on the streets.”

The judge further held that a lot of children in the country are suffering in silence, urging schools to ensure due diligence while hiring teachers.

The case of Adenekan and his victim(s) is one out of many in recent times in the country. From the South to the North, East to West of the country, there is hardly a day that passes without reports of sexual assault, mostly against children (male and female) and women.

The culture of silence and the stigma attached to victims of sexual assault and their families have made many cases in the country to go unreported, Barrister Rachael Adejo-Andrew, the Chairperson of International Federation of Women Lawyers (FIDA), Abuja branch, said.

She said in the past, victims of sexual assaults were faced with accusations of leading their molesters on by dressing seductively, but with the increasing cases of defilement (sexual intercourse with a child under 11 years), such accusations have been proven to be not only ridiculous but such that only seek to shut down the victims.

As such, when the federal government decided to follow the steps of Lagos and Ekiti states, in having a sex offenders’ register, Adejo-Andrew opined that the secret cries of the victims and fears of the would-be-victims have reached the right quarters.

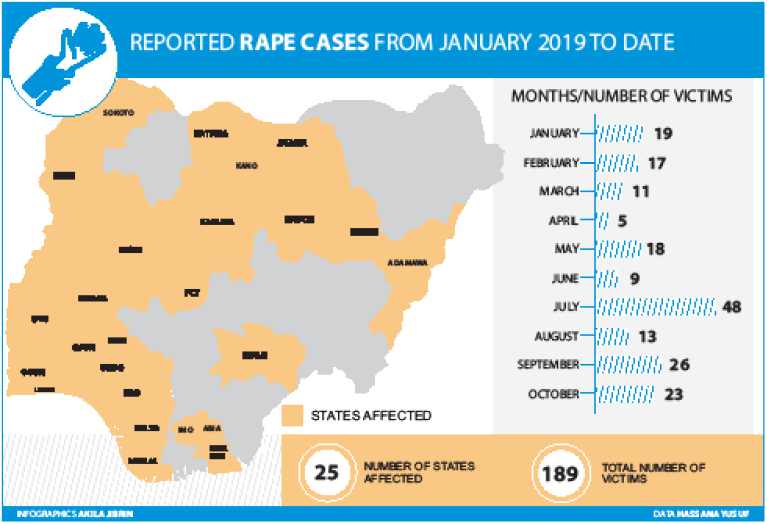

While unveiling the register for sex offenders in Abuja on November 25, the Minister of Women Affairs and Social Development, Dame Pauline Tallen, lamented the high rate of rape cases in Nigeria, putting the figure at over 2million victims a year.

The launch of the register was part of activities to mark the beginning of this year’s 16 Days Activism Against Gender-Based Violence, an international campaign to challenge violence against women and girls.

At the event, the Programme Director at the British Council in Nigeria, Dr. Bob Arnot, said the opening of the sex offenders register is expected to serve as a deterrent to potential offenders and contribute to the reduction of escalating cases of sexual assault especially against women and girls.

The European Union Ambassador and Head of Delegation to Nigeria and ECOWAS, Ketil Karlsen, acknowledged that sexual and gender-based violence is a global pandemic. This, he said, requires fundamental and coordinated action that would guarantee the safety and security of vulnerable women and children across the world.

On her part, the Deputy Secretary-General, United Nations, Amina Mohammed, said the increasing rate of violence against women has caused huge economic and psychology lost to individuals and the economy at large.

The enabling law for this register, the Violence Against Persons (Prohibition) Act 2015, provides in its Section 1(4) that a register for convicted sexual offenders shall be maintained and accessible to the public. The extent of this Act is however restricted as other states of the federation are yet to domesticate it.

The provision of this Act is similar to the practice in the United States, where all the states maintain and make the register of sex offenders accessible to the public.

However, in some countries like the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada and South Africa, the register is only accessible to law enforcement agencies.

What is a sex offender register?

The sex offenders register, according to The Sun newspaper in the UK, contains the details of anyone convicted, cautioned or released from prison for a sexual offence since September 1997, when it was set up in the UK.

More generally, Wikipedia defined a sex offender registry as a system in various countries designed to allow government authorities to keep track of the activities of sex offenders, including those who have completed their criminal sentences.

How it works

In the UK, all convicted sex offenders must register with the police, in person, within three days of their conviction, or release from prison and they must continue this registration on an annual basis, The Sun (UK) newspaper reports.

In the United States, a check on the designated website for sex offenders in the state of Colorado revealed that the offenders are classified into four groups: sexually violent predators, considered the highest risk sex offenders; multiple offenders, these ones have two or more adult felony convictions for unlawful sexual behaviour and one or more adult felony crimes of violence; felony conviction, a person who has been convicted of a felony sex offense as an adult; and those classified under failed to register, for failing to be captured, as required, with their local law enforcement agency.

Back home, an official of Nigeria’s Sexual Assault Referral Centre (SARC) in Kaduna, Juliana Joseph, explained that the register will be domiciled in the office of the National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons (NAPTIP).

“It is operated in two ways. First, since the judiciary is also part of the policy makers, when a person is taken to court and has been alleged to have perpetrated that crime, his/her name should be sent to NAPTIP. There is a session where they put alleged perpetrator,” she said.

Ms. Joseph explained further that when the person has been found guilty, the name is now transferred to the “real register” where names of offenders are kept.

She said the naming and shaming would be the first direct implication for any person whose name makes it into the register.

She added that since the register is online, it means that the person has gone global and the implication there is that countries would search the database before granting visa to would-be travellers.

Schools would also be expected to search the names of teachers to be employed to confirm if such has ever been convicted of any sexual offences, she added.

Sharing the opinion on the upsurge of sexual offences, Ms. Joseph acknowledge the presence of centres such as SARC across the countries as contributory to the attention sexual offences now seem to be garnering.

“People now know that when a person is raped and speaks out, the person will be helped. This gives confidence to people to come out. It is just like when HIV/AIDs came, when people realised that drugs were being given, those who had been hiding started coming out.

“We even have instances of people that were raped in the past but have not gotten over the trauma; they now come to the centre for counselling. It is because of this counselling, medical care and prosecution that people now have confidence to speak out,” she added.

Lawyers react

In the euphoria of the development, government must endeavour to fulfil some conditions to ensure that the sex offenders’ register does not fall foul of the extant laws, human rights activist, Barrister Hameed Jimoh advised.

He suggested that it must not concern a person under the age of 18 years and that it must relate to a convict whose rights of appealing the decision of the trial court have elapsed. He stressed that the right to appeal in criminal matters is a constitutional right that cannot be overridden by statutory provisions (VAPP Act included).

Therefore, government must wait for the mandatory three months for the convict to choose whether or not to exercise his right to appeal, according to the Court of Appeal Act, Jimoh said.

But Barrister Ogechi Abu, the Vice Chairman of the Nigerian Bar Association (Unity Bar), has a different opinion. She said the whole essence of the register would be defeated if the government has to wait for the case to be finally disposed of by the Supreme Court, going by the slow pace of justice administration in the country.

She suggested that instead of having to wait, the government can indicate under the sex offender’s name that his right to appeal has not been exhausted.

This is similar to the practice in the United States, where the government indicates whether the offender is still incarcerated or back in the community.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.