Countless women and girls have survived conflict-related sexual violence at the hands of Boko Haram in Nigeria’s North East and bandits in the North West. They are saddled with potential lifelong trauma and mental health disorders that affect their health and well-being and damage Nigeria’s goals of achieving peace, justice and strong institutions by 2030.

Zainab Aliyu was in a dilemma. She was five months pregnant and the pregnancy repulsed her. She feared that it could jeopardise her already turbulent marriage. If her family and community found out, they would stigmatise and shun her.

Zainab’s life changed in November 2021 when a group of bandits attacked a commercial vehicle she was travelling in. The 28-year-old mother of one was travelling from Kano State in North West to the North Central state of Plateau where she was scheduled for a fistula reconstructive surgery. However, it would take Zainab almost six months before she arrived at the gates of the Bingham University Teaching Hospital, which owns and houses the Vesicovaginal Fistula Centre in Jos. The bandits took her and other passengers hostage.

“On the first day of our abduction, the women were asked to line up. They raped a 14-year-old girl in the presence of her parents. Her mother pleaded with the bandits to spare the girl, while her father slumped in resignation, but the bandits had their way.

2023: No merger talks with Tinubu, Atiku – SDP

Sultan warns leaders against excessive materialism

“When it was my turn, one of them forced himself on me, and when he finished, he demanded to know why I was urinating. I told him I couldn’t control it and that I was on my way to the hospital when they attacked us,” she narrated in a whisper.

Even with the fistula, they did not spare her. The rapist told the gang leader that she was not good for his ‘pleasure’ and the rest of the bandits took her for themselves.

Weeks of negotiations narrowed a N2million ransom for her freedom to N800,000. Her relatives could only raise N200,000, which the bandits took, but kept her and threatened to execute her. After three months in captivity amid sexual abuse, Zainab and another victim escaped. Three days of meandering in the forest brought them to a village in the northeastern state of Bauchi, but the ordeal was not over as Zainab realised that she was pregnant. So, in May 2022, she went to the nurses at the Evangel Vesicovaginal Fistula Centre in Jos, the Plateau State capital, with a plea to terminate her pregnancy.

Residents of Nigeria’s northern region ravaged by the Boko Haram insurgency and banditry often raise the alarm that women are abducted, married off, raped or forced into sexual slavery.

The United Nations defines their situation as conflict-related sexual violence, which could be rape, sexual slavery, forced prostitution and pregnancy, among other dehumanising sexual violations subjected to women, girls, boys and men by state and non-state armed groups.

Often, in conflict situations, women and girls like Zainab are more susceptible to sexual violations. This was unanimously concluded in 2008 when the UN Security Council stated, “Women and girls are particularly targeted by the use of sexual violence, including as a tactic of war to humiliate, dominate, instill fear in, disperse or forcibly relocate civilian members of a community or ethnic group.”

Forced to marry a terrorist

Francis Sunday, a teacher in Kaduna State, was devastated when the bandits who abducted his daughter and 38 others from the Federal College of Forestry Mechanisation, Afaka in Kaduna State threatened to marry them off in 2021.

“They told us that if we didn’t meet their demands within the stipulated time they would marry off our girls to their people and kill the boys.

“They warned that we would never see our daughters again. The only thing we could do was to beg them for more time while we solicited support to meet their demands,” Sunday said, recalling a traumatising period for his family.

Sunday’s daughter and Pamela David are among the 1,440 students abducted in 25 school attacks in 2021, according to the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF). Though 10 captives were later released in two batches, Pamela and 28 others were released after 55 days in captivity and a huge ransom was paid to the bandits.

Now 21 years old, Pamela says the bandits used the April 2014 abduction of 276 girls from the Government Secondary School, Chibok, in Borno State as a tactic to traumatise female captives.

“We all knew the story of the Chibok girls, so we feared we could be married or sold off,” she said.

The abduction of the Chibok girls forced the world’s attention on Nigeria’s war with Boko Haram and its implication on the socio-economic wellbeing of women and girls. Although 57 of the girls escaped from their attackers and no fewer than 103 victims were either released or rescued by the Nigerian military in the last eight years, the whereabouts of dozens of the girls remains unknown.

However, in recent months, the Nigerian military has rescued 13 of the Chibok girls, amongst them Aisha Grema, Yana Pogu and Rejoice Senki and their children in the Bama area of Borno State. Their return home with offspring confirms the assertion of the late terrorist leader, Abubakr Shekau that the girls had been married off.

Relating the Chibok abduction to his daughter’s experience, Francis Sunday said, “These insurgents and bandits have weaponised the fear of sexual assault and forced marriages against girls and women.”

The tactic of sexual violence, including threats of forced marriages by non-state actors, is equally common in war-torn countries, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, where armed groups use sexual violence as an act of domination to humiliate, assert control over natural resources and territory, as well as punishment for perceived collaboration with other groups or state forces.

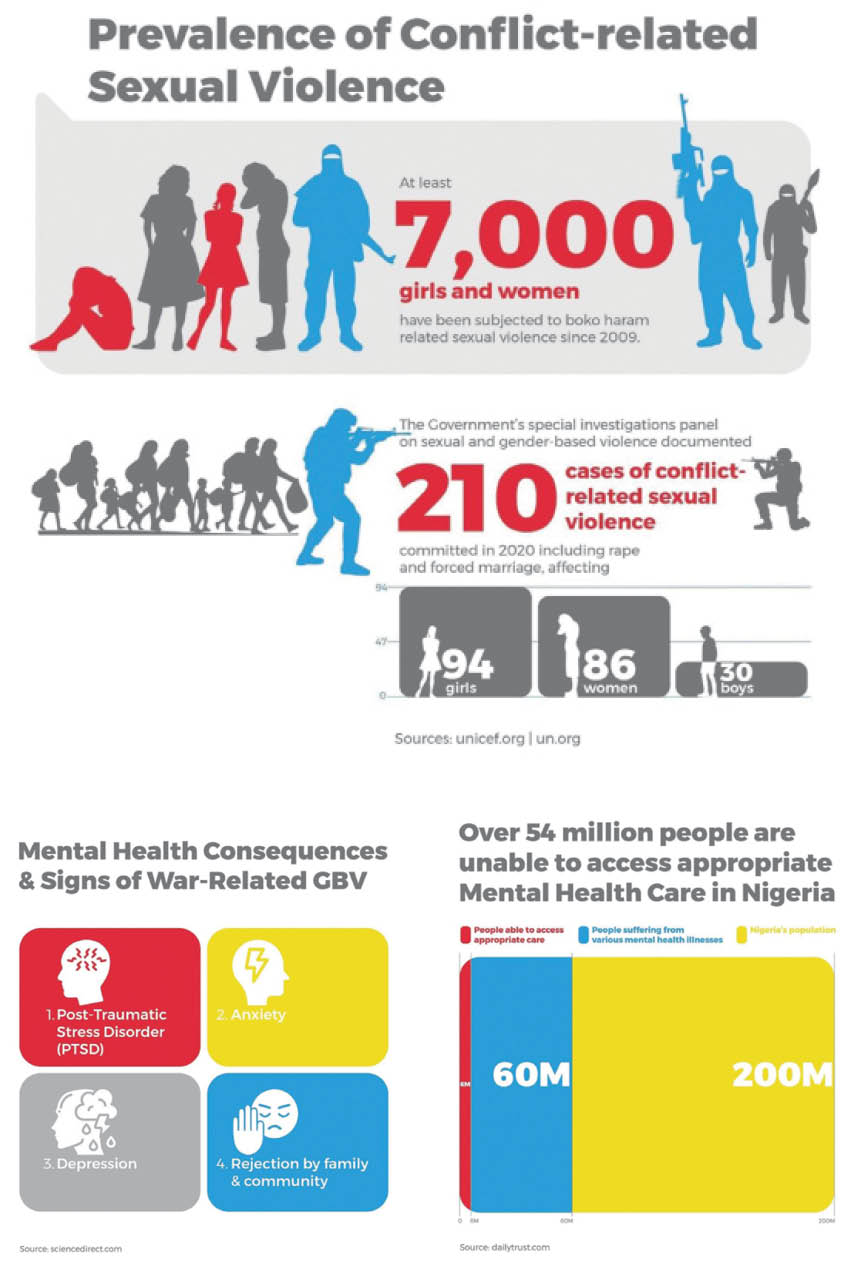

A 2017 United Nations report on children and armed conflict also revealed that at least 7,000 girls and women have been subjected to Boko Haram-related sexual violence since 2009. In 2020 alone, the report of the secretary-general of the Security Council stated that the ’Nigerian governments special investigation panel on sexual and gender-based violence had documented 210 cases of conflict-related sexual violence, including rape and forced marriage, affecting 94 girls, 86 women and 30 boys. The report stated that such crimes were chronically underreported owing to stigma and harmful social norms.

Traumatised and rejected

Halima Abubakar had suicidal thoughts when she and her four children escaped from her Boko Haram husband and his gang of insurgents in 2016.

Halima, who now lives in Yola recounted, “When I returned to my father’s house in Michika, Adamawa State almost two years after my abduction, I and my children were ostracised. I was called a Boko Haram wife and my father asked me to leave his house.”

The mother of six was instrumental to the eventual arrest of her husband who had fled to Niger Republic. She now works as a cleaner in Yola, her new home, but the emotional and psychological trauma of her marriage to a terrorist, the invasion of her community and years of captivity linger.

She also said, “I am no longer suicidal but I still have nightmares, and sometimes I fear that the terrorists might return for me.”

Sa’adatu Saleh Barkindo, who works with the Borno Women Development Initiative (BOWDI) to provide succour for women scarred by gender-based violence, said Halima had signs of severe depression when she sought help from the organisation.

“We started one-on-one counselling to calm her because she cried a lot. We then referred her to our psychosocial unit and she joined the safe spaces engagement,” Barkindo, whose organisation supports women like Halima with psychosocial and economic support said. Halima was gradually enrolled for tailoring and pasta-making training and was later employed as a cleaner.

“If her depression had persisted, we would have moved her to a mental health facility for psychosocial support, but with the engagement in our safe space, the counselling, psychosocial and economic support, she bounced back within five months,” Barkindo said.

Sumbo Ojegbile, the matron of the VVF centre in Jos, told Daily Trust on Sunday that just like Halima, Zainab Aliyu had telltale signs of psychological trauma when she arrived at the centre.

“Little things triggered her. She was startled easily and kept asking us to terminate her pregnancy,” the matron said.

Mental health experts warn that if left to fester, conflict-related sexual violence could breed a population of women and girls who suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Dr Abdurrahman Ashiru, a psychiatrist at the Federal Neuro-Psychiatric Hospital in Maiduguri, Borno State, said this could further lead to substance use disorders with adverse repercussions for the society.

Dr Nafisa Hayatudeen, a psychiatrist at the Federal Neuro-Psychiatrist Hospital in Kaduna said the survivors of conflict-related sexual violence would exhibit acute stress reactions such as heightened irritability, moodiness, whipping spells, restlessness and agitation.

It is not clear if Halima and Zainab have been officially diagnosed with PTSD, but the two women exhibited some signs, according to the prognosis Dr Abdurrahman Ashiru, who said one of the standard criteria for diagnosing PTSD was re-experiencing the incident in the form of nightmares.

Other signs include avoiding thoughts of the traumatic incident, as well as hyperarousal, where the patient is easily startled or frightened. “If someone has these three symptoms, we can confidently diagnose them with PTSD,” he said.

Zainab’s case was complicated by a pregnancy and an unfriendly abortion law that makes the termination of her pregnancy illegal in Nigeria.

Abortion, which carries a sentence of up to 14 years in prison, is only permitted when it is done strictly to save the life of the mother. This situation presents a dilemma for rape survivors, who could end up with more psychological and emotional trauma.

“My husband no longer answers my calls,” Zainab told Daily Trust on Sunday in June, expressing fear that her marriage may be over due to the pregnancy.

Her fear aligns with the findings of a 2016 study published by Public Health which show that social exclusion, such as family, community and spousal abandonment, could be a consequence of war-related sexual violence.

“At the beginning, he assured me that he would come to the hospital when the nurses told him that I had escaped from the bandits. When he found out that I was pregnant, he made it clear that he didn’t want a ‘bastard’ and stopped answering my calls,” Zainab told Daily Trust on Sunday.

A research reviewing 20 studies, conducted between 1981 and 2014, showed that mental health outcomes for women like Zainab included PTSD, anxiety and depression, while the main social outcomes are rejection and spousal abandonment.

This is why the 1960 UN Security Council resolution reaffirmed that countries and the international community must increase access to health care, psychosocial support, legal assistance and socio-economic reintegration services for victims of sexual violence.

However, not many Nigerians get psychological support. In a country of about 200 million people, of which over 60 million suffer from various mental health illnesses, the president of the Association of Psychiatrists in Nigeria, Professor Taiwo Obindo, recently said that only 10 per cent of the 60million accessed appropriate care. This leaves a 90 per cent treatment gap for mental illness in the country.

According to Dr Abdurrahman Ashiru of the Federal Neuro-Psychiatric Hospital in Maiduguri, Nigeria has less than 200 psychiatrists, which is below the World Health Organisation’s recommended ratio of one psychiatrist for every 100,000 people.

Dr Ashiru’s submission was corroborated by Professor Shehu Sale, the medical director of the Federal Neuro-Psychiatric Hospital in Sokoto State, who recently said there was only one psychiatrist for every 500,000 people in Nigeria.

Pamela David and Halima Abubakar form part of the 10 per cent of patients with mental disorders, who have received some form of care after they exhibited symptoms.

Dr Nafisa Hayatudeen said some of the signs that one needs to seek help included inability to tolerate loud noises weeks after the incident, being startled easily, anxiety and being paralysed by the fear that the incident would happen again. She added that problems with sleep and nightmares and inability to live a normal life also pointed to the need to seek medical attention.

“All these are signs that there is a problem that would need additional treatment beyond psycho-social support,” she said.

While Pamela and Halima have received treatment, they still get jumpy and have nightmares occasionally when they remember the ordeal.

Francis Sunday was forced to change his daughter’s school a year after the abduction because she was no longer responsive to the environment where she and others were abducted.

“We took her for psychotherapy and changed her school. She told me she could not stay in the old school because hearing somebody opening a door would make her want to jump out of the window. It took her a long time before she recovered,” he said.

Zainab Aliyu received counselling at the Evangel Vesicovaginal Centre in Jos, where she sought help, and it helped her come to terms with her pregnancy. She delivered a baby girl in late August. However, faced with rejection from her husband, the state of Zainab’s mental health after she left Jos with her newborn and moved to her mother’s village in Kano State remains unknown.

This report was supported by the Africa Women Journalism Project (AWJP) in partnership with the International Centre for Journalists (ICFJ) and the sponsorship of the Ford Foundation.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.