More than 28 million passengers pass through Johannesburg’s OR Tambo International Airport every year. But on the morning I arrived, at around 4am, there was only a handful of flights. The hallways were empty as I went through customs and immigration.

Officials checked through papers, duly stamped passports and handed them back. A police officer beckoned. He wanted to have a separate look. I confidently handed them over. He found nothing to complain about. Then he asked a question you get asked a lot in Nigeria.

“Anything for the boys?” He was asking me for a tip. I said, “Sorry, nothing for now. I didn’t know I’d meet you here.”

I wasn’t being flippant; it was the truth. I had just around $40 on me and had yet to change it into Rands.

And I wasn’t surprised at the question. I just expected better. One journalist I worked with once got asked the question at Lagos airport. He replied, “That’s corruption. I’m a journalist, you know?” The immigration official he spoke to said, “Go and write and report and write, you think that’s going to change anything? Nothing will happen.”

My South African policeman waved me through with a terse welcome toward the exit gate.

I was only the first of some 30 people due to arrive in Johannesburg for a workshop for journalist fellows in early childhood development. I felt alone until I spotted my pickup. Not really spotted him. Blythe was about the only one standing in the reception area but he held up a sign that said ICFJ Fellows. He’d also be the last person I see on my return trip. We got on first-name acquaintance.

Then began my experience of South Africa. First lesson: know your left from right.

I naturally moved to the passenger side of Blythe’s sleek Hyundai. I reached for the door, and Blythe said, “Would you like to drive?” I was perplexed until I saw the steering wheel on the right side, the side a passenger would have taken in Nigeria. This wasn’t Nigeria. In South Africa, cars are right-hand drive.

Second lesson: traffic drives on the right side of the road. Imagine my shock when we pulled into traffic and I found oncoming cars bearing down on us. I jumped in my seat, screamed at Blythe that he was driving on the wrong side of the road. Then I remembered we weren’t on the wrong side when the oncoming cars just harmlessly slipped by.

He asked where I came from. I thought that was obvious. Nearly everyone I’d met so far could tell from a glance. I wasn’t flamboyantly dressed or talkative. That ticked two boxes on his nationality checklist. He thought I was Chadian or Ivorian. His mouth fell open when I said I was Nigerian.

“You don’t say. I never would have thought!” he exclaimed. That goes to show first impressions are necessarily right. He had met with a lot of Nigerians and had developed a checklist: they were rather tall, dark, stood out in a crowd, talked a lot and loudly like they owned the place even when it was their first there, and had a peculiar shape of head.

It’s complete hooey but they are the misconceptions, half truths and utter lies that cloud Nigeria’s romance with South Africa. Johannesburg typifies the country’s struggle. It is not much different from the craze in the now-rested soap Egoli. It’s a local word for “place of gold”.

Entry to the Apartheid Museum. End of white rule has brought on new pressures on South African black population

The rush for gold brought in explorers and their families; the money built the early city; the indigenes were cast aside and treated as less than citizens. White rule made blacks feel inferior.

One legislative debate in the 50s on display at the Apartheid Museum claimed the white man is and will remain master in South Africa.

White rule has ended, apartheid is pushed aside, but the new reality of South Africa puts it at odds with the rest of the continent, and in particular, its blacks with Nigerians.

When white rule lost out, the country’s politics fell into black South African hands, but the country has been beset by high-level corruption, Nigeria style.

“It is too much,” Blythe tells me. “The country is worse than it ever was before Apartheid. It has been deteriorating.”

The lighted expressway rolls under us as he drives through pink pre-dawn light. I think the scenery of concrete and neon lights look impressive, maybe more than Abuja, and rival any capital in Western Europe.

“You think the highways are smooth and beautiful. It is actually worse, and has been worsening in the last 10 years.”

To see real deterioration, I head to Jo’burg’s central business district with Solomon Mabuka. Imagine the heart of Abuja’s financial district, the so-called Central Area, where all the businesses and offices hold sway.

Johannesburg’s CBD is a shadow of itself. It stands in shadow of the 50-storey Carlton Centre, which gives a 360-degree view of the city. It is a maze of square grids and crawling traffic.

The high rises are still there, the only sign of once-known prosperity. Now they are stuck in the middle of ghetto conditions springing around. Rising waves of crime have chased away the businesses.

View from the 50th floor of Carlton Centre shows the sprawl of Johannesburg’s central business district where crime has sent businesses. High rises once maintained on gold money groan in filth

Mabuka warns me not to venture out of his sight. “You would be robbed in broad daylight and nobody will stop to help you,” he cautions, his gaze earnestly negotiates traffic. He doesn’t even let his passengers put the windows down, lest some possession be snatched in traffic. That happens in Nigeria too, I muse.

Worse than the CBD is Hillbrow. “Tell anybody I took you to Hillbrow, they would scream,” says Mabuka. It is the worst of the ghetto, rife with crime. The buildings-once well-manicured offices and residences-are rundown. People who lived and worked in them have fled to newer settlements like Rosebank and Sandton City, where they feel more secure. People who lived in them were mostly whites. The blacks were the security guards and servants.

“What do you call that place in Lagos, that ghetto that is so rough you don’t feel safe?” says Mabuka.

“Ajegunle,” I ventured.

“Yes, this is our Ajegunle.”

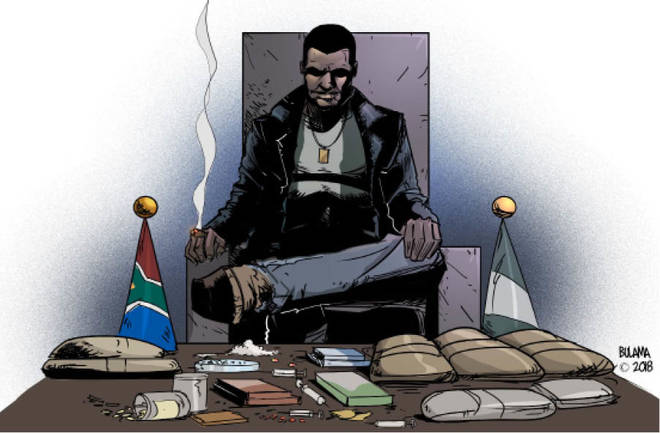

Mabuka used to live here before moving out with his family. He still passes through. He feels safe because he is known here. Here is also where I find Adesuwa Restaurant. Igbos, Yorubas, many Nigerians live here, despite the deprivation. Drugs, crime, prostitution is extensive and structured and stereotypical. Nigerians do the drugs, Zimbabweans do the thefts, I am told.

The number of Nigerians in South Africans is uncertain, and new migrants get there daily. Not all are undocumented and causing mischief. Nigerian doctors work in hospitals and lecturers teach at universities. Their businesses thrive. Many do legal work and don’t live in Hillbrow.

But Hillbrow typifies the contest field South Africa blacks share with Nigerians.

Resentment against foreign nationals have fuelled attacks. February last year, police used water cannon, rubber bullets and stun grenades to disperse anti-immigration protesters in Pretoria.

The country’s unemployment rate is 25%, and protesters say immigrants are taking their jobs.

A professional who regularly flies out of Lagos to spend time teaching in South Africa believes Nigerians are causing a disruption in South Africa. Not just in South Africa, but also in Uganda, Kenya, many countries he’s visited.

It is not the kind you would notice in statistics. Many Nigerians undocumented are hustlers-the illegal migrants doing any and all kinds of jobs to stay alive, unwilling to return to Nigeria.

They don’t laze around, they double down, make the money and splash it. And it flies in the face of the struggling black South African man.

“Imagine you are in a night club. The Nigerian guy is so loud. Once he enters, you’d know it. He’d declare open bar and take over the entire club. And when he’s leaving, the car you see him driving is out of this world,” he explains. “The average South African just can’t compete.”

The frustration comes from historical oppression, he says. First the white man oppressed the South African black man, took their women against their will. Now the white man is out, the Nigerian men have come in and are spoiling their women with money and buying them over with flamboyance. It is moving out from under one oppression and ending up under another.

Kwazi, a videographer, accompanied me to Diepsloot, Afrikaans for “deep ditch”. It is a densely populated township in the north of Johannesburg. He once worked behind the camera on a music video shot in the city. At a wrap-up party, he found the producer fling open a hold-all, stacked full with Rands.

“I was shocked. I was like, how do you get all this money. He said to me, drugs. Just like that,” Kwazi recalls.

Kwazi says it isn’t that all Nigerians are into crime in South Africa, but that many of the people involved in drugs are Nigerians.

“Who buys the drugs?” I asked.

“South Africans,” he said.

Glass walls on display at Apartheid Museum depict inflow of nationalities with the gold rush. They remain part of South Africa’s modern story

With drugs come gangs and turf wars that have left some communities no-go areas.

Hours after arriving in Johannesburg, I looked up fresh attacks. A mob destroyed four shops and several houses belonging to Nigerians in Krugersdorp, near Johannesburg.

Leaders of the Nigerian community said many Nigerians fled their homes amidst concern they [South Africans] were regrouping.

“Iam amazed and emotionally down as calls from panicked Nigerians flooded my phone from various Provinces,” Adetola Olubajo, president of the Nigerian Union in the area told News Agency of Nigeria.

In succession, one Nigeria was killed in Durban, another in Rustenberg. Two weeks earlier, taxi drivers burnt at least five Nigerian-owned shops and houses. Their allegations: Nigerians sold drugs to a gang that attacked their members, another abducted and raped a 16-year-old South African girl.

The Nigerian community said no Nigerian was arrested for rape or drug offences, calling the allegation “false and spurious”.

Xenophobic attacks on Nigerians in South Africa, prompted calls for boycotts and expulsion targeting South African businesses operating in Nigeria.

In 2012, South Africa expelled 125 Nigerian travellers for not having valid Yellow Fever certificate. Nigeria expelled 56 businesspeople in retaliation. Both countries later sat to ease visa restrictions to enhance bilateral relations.

But that is still up in the air. The elephant in the room still carries into international travel. Nigerians complain procedures for getting a South Africa visa are unnecessarily tedious.

“They can deny you visa without an explanation, just for the heck of it,” a journalist warned me, when I applied for a visa in Abuja.

In Johannesburg, a South African professional turned the story. “Getting a Nigerian visa is just so, so, so difficult,” she swore.

The tit for tat hasn’t let up.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.