Few people in this world could be said to have been as unfortunate as Mrs. Alice Blunden. On one normal day in 1674, Mrs. Blunden consumed poppy water, an intoxicant of her day, and passed out. She was feared dead, and the local doctor examined her and pronounced her as such.

A message was dispatched to her husband, who was on a trip, and he asked that she not be buried until his return. Back in those days, these messages, as you can imagine, took time. So, her family, fearing that she would decompose rather quickly because of her sizable girth and the heat—and, of course, the absence of morgues at the time—decided to bury her immediately.

Two days later, children playing close by thought they heard noises from the grave and they reported this to adults. It took a whole day for an adult to come and investigate and took some time to find a gravedigger to dig up poor Mrs Blunden, who had been buried alive. She had been calling for help and trying to free herself from the grave for three whole days.

By the time they got to her, she seemed to have died for real this time, but the signs of her struggle were very evident. Not sure if she was dead or alive, they reburied her and appointed a man to guard the grave, just in case she woke up and called for help. That night, the man left his station and whiled away time at the pub.

The next morning, they decided to make sure and dug up the grave once more. To their surprise, they found that Mrs Blunden had woken up and desperately tried to free herself from her ill-fitting coffin and her premature grave, injuring herself and tearing her face in desperation and fear. But this time, she was dead for good. So they buried her a third time.

When her husband returned and discovered what had happened, he decided to sue everyone who was involved in the burial of his wife.

Very few people have had the misfortune of being buried alive twice like Mrs. Blunden, perhaps with the exception of Nigerians. Mrs Blunden’s relationship with the people who buried her today rings like a metaphor for Nigeria’s relationship with its rulers (rulers is a deliberate choice of word as distinct from leaders).

We Nigerians are being buried alive today by economic hardship, commodity prices, and insecurity in this country. Yet, like Alice Blunden, we are clinging to hope that if we scream, kick, and knock, someone will dig us out of this and give us a new lease on life.

This hope renews with every regime change, democratic or otherwise. But every time, more heaps of dust are dumped on us, over and over and over again. There is no regime change in this country that has not been greeted with some hope—less so recently, I guess. At every point, we have said, well, certainly things can’t get worse than they are now, can they? Yet, every time, fate laughs in our faces.

Across the country, there have been sporadic protests over the rising cost of commodities and the general hardship of life. This has been the toughest thing in living memory yet, as in the case of one buried alive, the protests have lacked coordination and a national reach to make the government take immediate action. We are confined not by a physical coffin but a metaphorical one, the coffin of division and a lack of collective purpose.

Earlier this month, Justice Ambrose Lewis-Allagoa of the Federal High Court in Lagos, in response to a suit by the erudite legal luminary, Femi Falana, ordered the federal government to immediately fix prices for specific commodities according to Section 4 of the Price Control Act. The court gave the FG seven days to comply. Well, those seven days have passed. Prices have continued to skyrocket, and, not helping matters, the naira has continued its free fall against the dollar.

Of course, that seven-day mandate is impractical. A price control regime is a complicated affair, one that requires extensive surveys, analysis, and various moving parts. Ultimately, once it goes against free-market policies—except in this case, the market is a little too free. Price control, however, is meant to be a temporary measure, one that helps stabilise a system before a sustainable policy kicks in. But we know how temporary interventions in Nigeria have a tendency to become permanent.

Fuel subsidy, for instance, was introduced in the early 1970s as a temporary measure. It is 2024 and despite public proclamation of its demise and burial on May 29, 2023, evidence suggests that the government is still paying subsidies. Price control, on the other hand, has attendant problems such as shortages of goods, rationing, dilution of product quality, and illegal or black markets, as we tend to call them here.

However, it would seem the government is mulling compliance with the court order, at its own sweet time. The vice president, Alhaji Kashim Shettima, this week announced the FG’s plans to establish a commodity board, whose duties will include regulating commodity prices.

I think it is sad that we got to this point, but I also realise that we must act quickly to curtail this downward spiral into economic anarchy that the country is heading into. Any kind of collapse is unsustainable, but this level of collapse Nigeria is experiencing is even more so. If this commodity board is to be established, it must be clear that its mandate in enforcing a price control regime is short-term, which will at least help stall anarchy and hopefully give the government the time to address the main problems causing the chaos – the stabilization of the naira, increasing local production, and boosting the local economy.

The lessons of the fuel subsidy regime must be learned, and temporary solutions must never again be allowed to remain permanent.

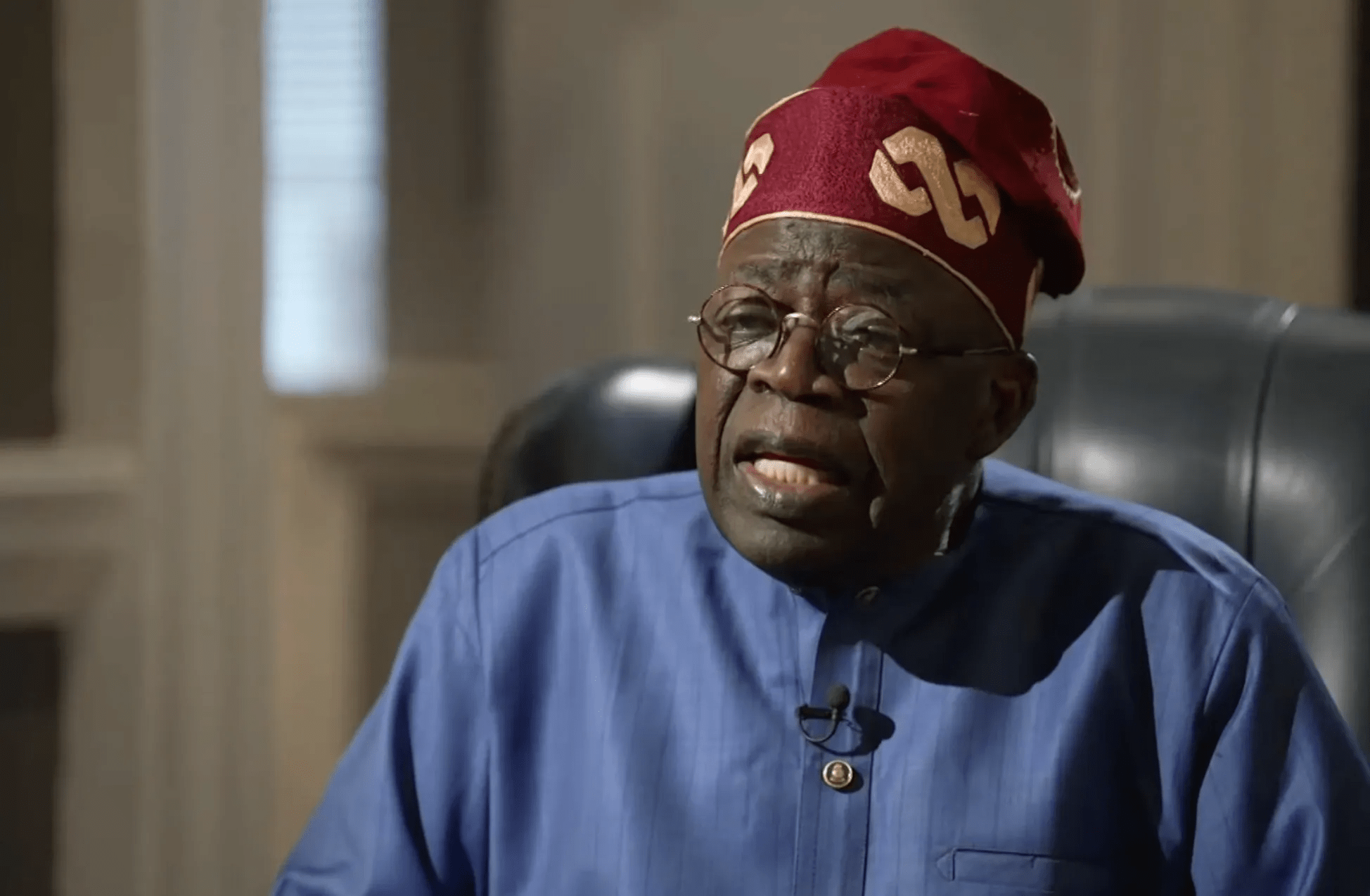

Yes, this government inherited a collapsing economic structure – if one can call it that – from the previous administration, but the runway for excuses is quickly running out. It will soon be a year since President Tinubu has been in charge. It has been a very difficult period for Nigerians. The new captains in charge must take responsibility, own up to the questionable and sometimes rash decisions that have catalysed this spiral, and continue to heap dirt on the grave of the average Nigerian buried alive under this hardship.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.