Education in the northern Nigeria is considered an entry point to empowerment, yet for most girls in rural areas like Jili, this remains a distant dream, given the prevailing poverty and infrastructural constraints with a deficit in supportive policies and funding at the state level.

In spite of huge investments in education, Kano still has only 46% literacy among girls, compared to 73% among boys, according to the Nigeria Digest of Education Statistics. This report looks at how poverty, coupled with social and infrastructural barriers, limits the educational opportunities for girls in Jili and other communities in Kano.

Government Policies and Their Reach in Rural Kano

- Female athletes urged to participate in marathon races

- Tinubu pitches investments in food, security, solid minerals, others

As pointedly captured, notwithstanding the establishment of policies like the Free and Compulsory Basic and Secondary Education Policy designed to deal with the inequalities of access in education, this policy is implemented uneven around the nation. But while other policies such as the GRESP and AGILE on the other hand remain good deals toward girl child education that brings about positive impacts, though they remain difficult to reach communities located at very rural locations including Jili.

The Kano State Development Plan of 2022–2025 recognized the need for urgency in eradicating gender disparity, yet progress is slow, particularly in economically disadvantaged areas.

Economic and Social Constraints on Education

The families in Jili, a farming community with 10,000 people, depend on subsistence farming and small-scale merchandise, earning barely enough to meet basic needs. In spite of the state’s policies, poor families cannot send their children to school due to hidden costs like books, uniforms, and transportation. Gender-based norms and early marriages, still prevalent in the community, often deprioritize girls’ education.

According to the Education Strategic Plan (ESP) (2009–2018), gender gaps are most pronounced in poor households where decisions about education often exclude girls. Although frameworks like GRESP and AGILE exist to support girls, their impact is limited in rural areas like Jili, where access to education is already severely restricted.

Educational Facilities and Resources in Kano

While Kano has 7,048 primary schools, according to data from the Annual School Census in 2021, junior secondary schools sharply drop to 1,148 and senior secondary schools to 813. This gap is more disturbing in the case of girls, as while they top the number in primary school enrollment, their number drops in junior and senior secondary schools due to financial constraints and lack of access to schools nearby.

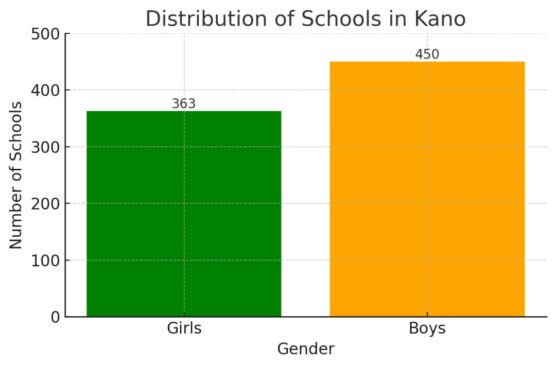

Dr. Kabiru Ado Zakirai, Executive Secretary of the Kano Senior Secondary School Management Board (KSSSMB), says distribution has to be done with accessibility in mind. He said, “Out of 813 senior secondary schools in Kano, 450 are for boys, while only 363 are for girls, with the rural landscape often presenting logistical barriers.”

You have to site a school where it will be accessible to the majority. The tendency is that rural areas, being far-flung, sometimes are neglected because of big challenges in transportation and logistics”, said Zakirai.

He proposes the establishment of 92 additional boarding schools across Kano’s 23 education zones, saying these gaps have to be filled, adding that boarding schools offer families more feasible options for their daughters’ education. He admitted the financial challenge of sustaining them.

Budget Allocation versus Reality

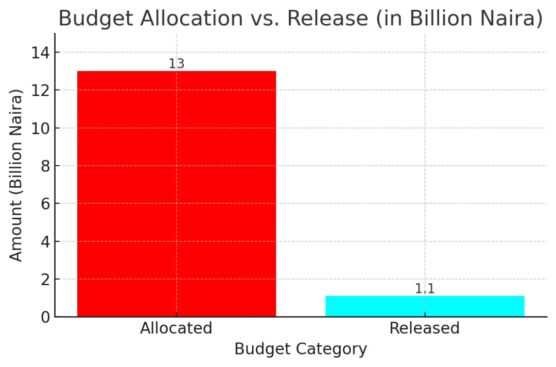

Kano’s government apportions 31 percent of its 2025 budget to education from 29 percent in 2024, yet budget releases for actual education priorities remain slow.

For instance, while over N13 billion was allocated in the first half of 2024, only 1.1 billion was released, which represents about 8.9%. Such a gap has stalled vital projects, including those under the AGILE project, which targeted over 48,500 girls with transportation, school supplies, and allowances.

Amina Kasim, the Girls’ Education Coordinator at the Kano Ministry of Education, stated that the governor was committed to education, while also pointing out delays in releasing funds.

Kasim says, “We have not received funds for some approved projects since 2023.” She stresses that such bottlenecks undermine progress in increasing girls’ education.

Government Efforts and Challenges

Notwithstanding these, the government has begun enacting gender-sensitive policies and projects on the distribution of uniforms, increased feeding allowances, and a revised Teacher Policy on Girl Child Education. Furthermore, Commissioner of Education Umar Haruna Doguwa criticizes the strategic plans of previous administrations as unrealistic and thus hints that new policies, including a revised Kano Education Law, 2024, and a Girl-Child Education Policy, are in the offing to give girls’ education a better foundation.

“We have so far employed 5,643 teachers, and most of them are women,” Doguwa said. “Our aim is to close the gender gap in teaching staff and make sure girls have more female role models in schools.” He equally berated the neglect of the education sector by the past administration, which has plunged the nation into the current situation. “The education system has been neglected since 2015,” Doguwa said.

“Many girls are being left behind due to poor infrastructure and lack of proper support, but we are committed to a reversal of this trend.”

In addition to teacher recruitment, Doguwa highlighted the state’s efforts to improve educational access for girls. “We have refurbished 72 school buses, 57 of which are now operational, to make transportation safer for girls. We’ve also provided free uniforms to students and doubled the budget for school feeding programs,” he said.

The government has also been providing financial support through the Conditional Cash Transfer project, with 48,500 girls getting ATM cards to facilitate their remaining in school. “Through the CCT, 20,000 girls were given N20, 000 each as support for their education to keep them in school,” said Doguwa.

Governor Abba Kabir Yusuf has further reassured such commitment by the government in revitalizing the education sector in Kano while addressing the state assembly recently. “We have submitted six draft policies, including the Kano Education Law, 2024, and the Kano Teacher Development Policy. These policies will address the challenges in education and ensure that every girl in Kano has the opportunity to succeed,” the governor said.

Perspectives of Parents and Students on Educational Challenges in Jili Village: The burden of educational challenges in Jili is not only felt by the students but also by their parents, who often have to make difficult choices between their children’s education and survival needs. Parents in the village, especially those engaged in subsistence farming and small-scale trading, are concerned about the future of their children, particularly girls.

Amina Bello, a mother of three, has this to say about the difficulties her daughter has in pursuing a good education: “It is disheartening, really, to see my daughter struggle every day, wanting to go to school. The school is far, and she often walks alone-sometimes in bad weather.

“I cannot afford to send her to a better school, and even then, when I can, the supplies are not available. I want her to learn, but I know that at some time, I will have to choose whether to keep her in school or marry her off, because I simply cannot afford both. I just want her to have a chance at a better life, but our poverty limits that chance.”

To Amina and many parents, education remains a dream blurred by the cold realities of rural poverty and the lack of educational infrastructure.

A father of two, Mohammed Abdullahi shares in this frustration at the inability of the system to address some of the peculiar challenges that their rural community faces:

“It is the government’s promise to help, but we have yet to see these changes in our village. We don’t have enough schools; the ones we do have are in a very deplorable state.

“The distance to the nearby high school is too much for my children, which is further than I can really afford. I fear she might not be able to complete her secondary school due to scarcity in such facilities. It hurts much as I want her to be successful; it would force her out of school to help with farming.

Students like Hauwa’u Alkasim, shared the struggles they have in trying to access education. “The biggest challenge we face is that we don’t have a secondary school building of our own; we are using primary school classrooms,” Hauwa’u reflected on the challenges.

“Besides, we have inadequate learning materials at school, such as books, modern blackboards, and others. On the other hand, I have started thinking of engaging in petty trading and eventually getting married as I grow older, just like those before me, because in many cases our parents cannot afford to sponsor our education.”

Another student, Maimuna Isah, said: ‘We have a shortage of teachers, and we also lack learning materials, especially for science subjects and others. Moreover, students don’t like attending school because of the long distance, and we have to walk there on foot. Many of us also engage in petty trading,” she explained.

These voices really capture well the complicated intersection of poverty, gender roles and access to education. Parents like Amina and Mohammed, students like Hauwa’u and Maimuna, are shown the way by a system which promises much yet delivers very little, particularly for girls in rural settings.

A series of steps have to be followed for addressing the inequality in the case of girls’ education within rural Kano.

First, enhancing availability involves the construction of more schools at remote locations and renovation of facilities at existing ones.

More focused support in the form of transport facilities, learning materials, and other financial benefits to families would lessen the barriers to enrollment. Funds allocated for education should be released by the government in time for effective implementation of current programs like the AGILE project.

This will help in the implementation of policies like GRESP and AGILE, and at the grassroots level, awareness will be improved to ensure that such policies are relevant and accessible to rural girls. The training and recruitment of competent teachers, especially female role models, should also be sustained in order to inspire and guide girls throughout their education.

In addition, local communities, governments, and NGOs will have to collaborate towards putting in place a relevant, sustainable, and gender responsive education system for the realization of positive results that can empower the girl child.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.