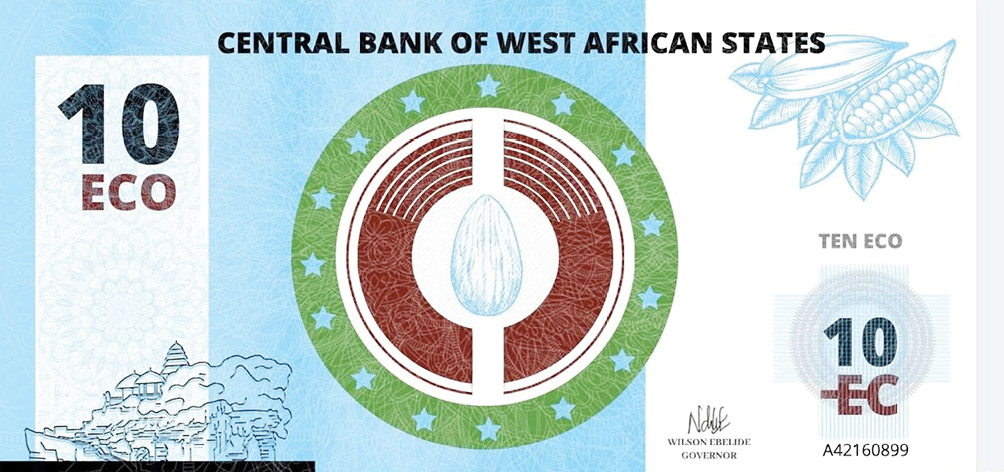

Would the introduction of the Eco, West Africa’s planned regional currency, have shielded the sub-region from the current macroeconomic instability, including a possible recession, that stares the 15 member states in the face? The answer belongs to the conjectural now, since the currency is yet to the introduced, about two decades since it was first approved by the leaders of the bloc.

The potential advantages of such a monetary union have been profusely documented by economists. In the case of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the adoption of Eco was expected to ease trade among the members, that is, enhance cross-border trade in the region that was known for stringent border controls along the Nigeria- Cote d’Ivoire route. It is also expected to reduce or eliminate costs of currency conversion; make the region more attractive to investors through the creation of a larger single market, among others.

Flood: 79 die in Anambra, Enugu – NEMA

Fear looms in Nigeria as Indian syrups kill 66 children in Gambia

Despite the congruence of the markets in the area, trading amongst neighbours is perhaps as difficult if not more challenging, as trading with Europe or Asia.

Sometimes, it is cheaper to import from Asia than to buy from neighbouring countries and the common international passport is only as good as the visa on arrival for tourists into the countries, with neither privileges nor trust of brotherhood.

The Euro, currently used by 19 European states, has played similar roles that the Eco was expected to play in West Africa, since its launch on January 1, 1999, says Abiola Rasaq, former chief economist for the United Bank for Africa Plc.

“The Euro provided a rallying point for the Euro area, broke a major barrier to cross-border trade and created a strong internal demand that spurred the expansion of manufacturing and industrial sectors. It was strong leverage for global competitiveness and indeed offered more choices and opportunities to the European consumers,” he said.

According to him, “While the euro is currently used by nineteen of the 27 members, it has clearly served as a pivot on which many economic ties and common policies were built in the Euro area. Indeed, countries like Greece, Portugal, and Italy would have struggled more to survive the past decade without the silver lining of the Euro. That currency unification has been a rallying point through which individual weaknesses of the member nations are managed and respective strengths are leveraged.”

As Dr Lizzie Kings-Wali, founder and CEO of Blackstone Capital Limited noted, “there are benefits from a single currency adoption in West Africa but there has to be both explicit and implicit trust amongst the member countries, especially as regards coordination of fiscal and monetary policies regarding issues which would remain within the sovereignty of the member countries”.

She added however that, “as exciting as a uniform currency sounds, there is a need to break down the barriers mobility of people, goods and services for a single currency to have full effect, else the benefits would be lost in the mist”.

These and more gains are usually possible a monetary union as part of economic integration usually follows earlier stages that involve macroeconomic policy harmonization and elimination of distortions among the members. These usually include tariff harmonization, free movement of persons in the region

If the prospects for the attainment of the common currency were bright say 10 years ago, today, they have dimmed. Adoption of the currency by ECOWAS was to be based on ten principles, known as convergence criteria. These policy goals needed to be achieved to bring the economies at par on core macroeconomic issues. Once in place, they are expected to make easy application of common monetary and fiscal policies across the collaborating state.

Out of the ten criteria, four were said to be key or primary ones. These are measures designed to enable the cooperating member countries to strengthen their macroeconomic balance before fusing into such a union. Such a position is expected to help

These are the attainment of a single-digit inflation rate at the end of each year; a fiscal deficit of no more than 4% of GDP; central bank deficit financing of no more than 10% of the previous year’s tax revenues, and a minimum of three months’ import cover of gross foreign reserves.

A look at these criteria reveals pointedly that problems associated with them are at the heart of the malaise afflicting the sub-region, and indeed most of the African continent. Take inflation, for example. Inflation in two of the biggest countries in the group has hit the rooftop: 33.9% in Ghana, and 20.5% in Nigeria. It is however lower in most others: 6.2% in Cote d’Ivoire; 7.5% in Mali; 6.48% in Liberia, and -0.3% in The Republic of Benin, an increase from -1% recorded in July this year. The inflation rate in Ivory Coast is the highest since 2011; the rate was 5.4% in the month of July.

If the region seems to be doing fairly well on inflation (given many of the smaller members have single-digit figures, the debt-to-GDP criterion may be a different matter, as the macroeconomic balance has deteriorated. In Ghana, the debt-to-GDP is as high as 78%, while the balance of payments deficit surged to about $2.5 billion in June. The government set out this year to reduce the budget deficit to about 7.4% from about 13.7% last year.

Nigeria is not faring any better. While its debt-to-GDP is currently at 23%, the deficit is unsustainably high, pushed by burdensome petrol subsidies that the government has found difficult to handle. Government expenditure is rising while revenue, which has been traditionally dependent on crude oil receipts, has been falling.

Talk about Naira, not Eco – Prof Adi

Nigeria does not need anything currency now, says Bongo Adi, a professor and development macroeconomist at the Lagos Business School.

“Whoever is thinking about Eco does not understand the monetary system. Money is a trust of a group of people and its power is derived by the number of people using it,” he told Daily Trust in an interview.

“That is why America has made sure everybody uses the dollar. Another currency that will be global very soon is Yuan (the Chinese currency), and the Indian Rupee.”

He blames the inability of Eco to take off on its failure to meet the network criteria of money. “The power of money derives from the people using it. It’s a network thing”.

He likens it to the mobile phone that everyone carries. “It is useless if there is no other person that can call you. The value of your phone is dependent on the number of people who can reach you. If only the same people can call you on your phone, nobody else can call you, your phone is useless.

The power of your phone is that anybody can reach you and you can reach anybody. This is the network effect. Money is about the network. What is the population of West Africa that is using Eco? And they also (except the Francophone countries) have their small, small currencies (Cedi in Ghana, the Leon in Sierra Leone, etc.)

“So you now have a currency that has inherent network (which is naira), and you are not talking about it but are talking about Eco that doesn’t have a network. So, how can it take off?

“What is the population of West Africa that is using Eco? And they also have their small, small currencies (Cedi in Ghana, the Leon in Sierra Leone, the Liberian Dollar, etc).

What Nigeria needs to do, he said, is to enforce the use of the Naira in the sub-region. “What a Nigerian President or CBN governor should do is to look for ways to ensure that transaction in West Africa is mediated through the Naira. Not Eco. You don’t need to do Eco. Eco what? he asked.

Adi said Eco can only work if Nigeria were to take the lead because most of the things in West Africa pass through Nigeria, including the shipment of imports.

Analysing the economics of the Eco currency from a network perspective, the don argued that “you cannot have naira, which is the dominant currency in the region used by more than 80 percent of the people and for more than 80 percent of the transactions in the region and then you have another currency, Eco. So now you have competing currencies”.

The population of the 15 member countries of ECOWAS has put variously by different sources, but WorldData.Info puts it at 407.68 million people. With Nigeria’s population also estimated about 214m or so, it means this country accounts for at least half of population in in the sub-region.

The delayed implementation of the single-currency policy in the sub-region has also been blamed on regional politics. Adopting it will give credit to French colonization, which is still very active in the Francophone countries, says Adi. The Francophone countries still owe their political and economic allegiance to their former colonial master, France, he pointed out.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.