On Tuesday, November 7, 2023, the Senate announced that dredging of the River Niger, River Benue and other river projects had been captured in the proposed 2024 appropriation bill as part of measures to combat recurring excessive flooding from Lagdo Dam in Cameroon and its attendant challenges.

The Minister of Water Resources and Sanitation, Professor Joseph Utsev, also said earlier that to restart the dredging of the two major rivers in Nigeria, the ministry has inaugurated committees to work on modalities for executing the project.

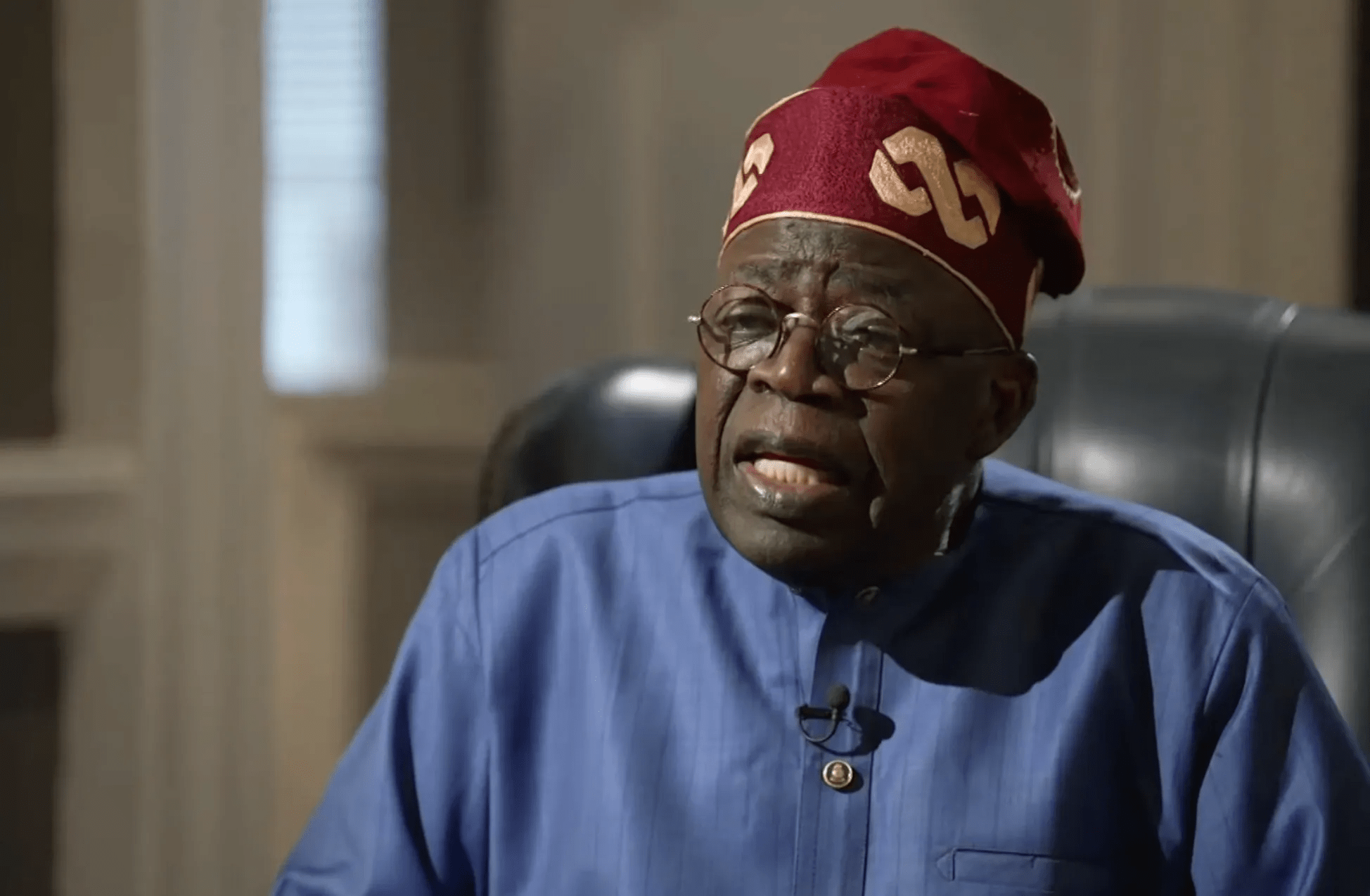

He added that “the committees will do the assessment on the feasibility of the dredging. After that, we will discuss it with President Bola Tinubu. At that point in time, we will make it open to all Nigerians to know where we are on the dredging of the two rivers.”

This is commendable, as dredging the River Niger would open it to all-year navigation, thus attracting barges, ferries and ships bearing cargo up to Baro in Niger State from Warri in Delta State, enhancing economic activities, reducing burden on highways, minimising accidents on the roads, and helping in long-distance haulage of goods, including oil and gas products to the North.

Media Trust pledges to absorb best graduating mass comm students of IBB varsity

ABU, Nairobi varsity sign pact on research activities

This quest to dredge the Lower River Niger predates Nigeria’s independence. But the late President Umaru Musa Yar’Adua broke the jinx when, on December 1, 2008, he signed a N34.8 billion contract for the project.

He then inaugurated the project on September 10, 2009, in Lokoja, the Kogi State capital, with a three-year completion plan. On November 2, 2011, under former President Goodluck Jonathan, the contract was reviewed upwards by the Federal Executive Council (FEC) with additional approval of N8.5 billion, putting the total contract at N43.3 billion.

In August 2014, Jonathan declared at an international conference and exhibition organised by the National Inland Waterways Authority (NIWA) in Lagos that the dredging of the 527 km of Lower River Niger from Warri to Baro had been completed.

And on January 19, 2019, President Muhammadu Buhari inaugurated the new Baro River Port, Niger State, as part of efforts to boost the functionality of the dredged Lower River Niger project, even though there was no road network linking the port with any federal or state highway.

Despite these official declarations, no badge or cargo ship has hauled goods via the river, signifying that stakeholders are shying away from using the river, a sign of things gone awry.

Indeed, Comrade Aminu Umar, President of the Nigerian Indigenous Ship Owners Association (NISA), said in 2016: “We keep hearing that the River Niger has been dredged down to Warri… I don’t think that river was dredged. Nothing has changed before and after the so-called dredging that they claimed to have done. To be honest with you, from the shipping community, we don’t think any dredging has taken place on that river.”

Yet, the River Niger and its tributaries remain one of the nation’s most critical natural assets. In the pre-colonial period, it was one of the most reliable channels of transportation and communication. But today, they have not fulfilled their promise.

Therefore, the current chat about dredging the River Niger and its tributaries should go beyond the business-as-usual award of contracts. It must now be executed to incorporate the goals of not just moving vessels alone, but also helping Nigeria reap cultural, economic, and tourism benefits.

For example, the Danube, Europe’s second-longest river, which flows through 10 countries in Central and Eastern Europe, and the Rhine flowing through Switzerland, Germany, and the Netherlands, is the backbone of the inland navigation between north-western European basins and the south-eastern Black Sea. It serves as a major international highway for trade, such that many industrial centres developed along the banks and are used to transport goods to the ports. Within it are also many important tourist landmarks.

Not so for our River Niger. Save for the major dams, especially Kainji, built along the River Niger, it would have been a mere geographical presence as there is little economic activity on it compared to its potential. So, the contract as contained in the 2024 budget must not just be about the removal of silt. And it must neither be executed shoddily nor a conduit for syphoning public funds.

This time around, dredging the River Niger must lead to opening up the communities along the river to sea-going vessels, increased commerce and trading activities, alternative source of transportation and an expansion for use by tourists and sightseers.

It must involve the building of embankments that would help control flooding and provide water for irrigation. This would enable Nigeria to take advantage of the looming vagaries of climate change as the embankments will be put to good use, depending on whether it is rainy or dry season.

Also, the dredging must meet the specific requirements of stakeholders, which would enable them to repose enough trust in the execution of the project towards deploying their vessels, barges and other heavy-duty watercraft to ply the waterways.

Moreover, NIWA, Nigeria’s waterways regulatory agency, should get serious with proper monitoring of the dredging projects by ensuring they meet the required standards. It is time to actually complete the project.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.