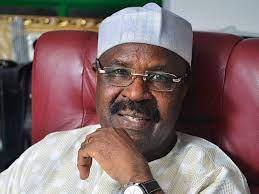

At their sitting in Yaoundé on December 10, Cameroonian lawmakers declared support for one of the most notable businessmen from West Africa and appealed to his South African antagonists to be fair to him. That’s the latest in a long-running battle that has drawn in governments of other countries in what began as a bad business relationship. El-Hadj Baba Ahmadou Danpullo, a Nigerian-Cameroonian, has been at legal war with one of the biggest banks in South Africa, and the clash of interests has taken a familiar dimension.

The tycoon’s nightmare, in the words of his lawyers, began when the new management of South Africa’s First National Bank (FNB) demanded early repayment of loans taken by their client in 2017 and agreed to be repaid over 10 years. The bank’s sudden u-turn in 2020, which was the immediate early repayment of the remainder, set in motion a cascade of diplomatic kickboxing and racially-charged accusations against the bank, whose action has been framed by the businessman’s camp as a “violent, anti-professional, racist, xenophobic, and inhumane crusade.”

In Cameroon, the local newspapers, especially the Guardian Post, have been dispensing updates on the consequences of the face-off around them and thousands of kilometres away. “Baba Danpullo’s assets worth over 500 billion FCFA seized in South Africa,” it reported on November 3, 2022, rousing the world to debate the justice of seizing such size of assets over what’s been reported as a loan of 12 billion CFA. The targeted properties were managed by the subsidiaries of Bestinver, the group the businessman founded to oversee his vast investments.

Even though The Guardian Post didn’t establish what triggered the bank to throw one of their prized customers under the bus, they have left enough combustible materials to spark international outrage around the case. “The loan,” they reported, “was meant to be repayable over 10 years,” and that “Baba Danpullo is uninterruptedly repaying without any problem despite the COVID-19 constraints.” The easiest inference, therefore, has become a question around South Africa’s hostile treatment of immigrants, the lethal bursts of xenophobia that have angered other countries to respond to treatments of their nationals in kind, an eye for an eye.

- IPOB attacks: Igbo avoid Christmas trips to South East

- Boko Haram attacks Borno village, burns silos, houses

To retaliate against the seizure and liquidation of Danpullo’s real estate assets in South Africa by First National Bank, the Cameroonian government moved against South African-owned businesses in their jurisdiction. Having secured an order to freeze the bank accounts of the South African operator MTN Cameroon and chocolate maker Chococam, along with the bank accounts of top executives of targeted corporate organisations, Paul Biya’s Cameroon got to send a message in solidarity with Danpullo.

Danpullo’s experience in South Africa has added a strange layer to the tales of black immigrants in what ought to be a haven for black people. Before his story began to waft towards the western axis of the continent, South Africa was already a pariah for its poorly-managed black-on-black violence, with black immigrants cruelly targeted, brutalized and killed by unwelcoming black citizens who, in several cases, rushed to justify their violence as a pushback on the economic hardship and unemployment in the country.

Even if we are to attribute such harassment and killings of blacks in South Africa to poverty, the one-directional pattern of such violence, with only a specific race at the mercy of the killers, paints a frightening image. Harming a random foreigner or immigrant may qualify as brazen xenophobia, but targeting a specific race is something different, something scarier, what some have referred to as Afrophobia. The criminals don’t go after non-black foreigners. And Danpullo’s story calls for deeper scrutiny of what truly is going on.

Towards the end of 2019, the South African government was compelled to apologize to Nigeria after a spate of attacks on Nigerians and other black nationals there instigated the destruction of South African-owned businesses across Nigerian cities. This was the most extreme reaction from Nigeria, and it was triggered by images of the attacks that trended online. But this shouldn’t be the language that appeals to South African authorities, to anyone at all.

What makes Danpullo’s case peculiar is that it shifts conversations around the safety of black immigrants and their businesses from the usual analyses of the tension among low and middle-income owners. The outrage since the legal baffle began has been that even wealthy black immigrants aren’t safe, and such suspicion drives a narrative that must be addressed before it becomes the trending subject of social media sensationalism.

The businessman has featured in a certain intervention in the case as a victim of white monopoly capital, a white-owned organization, which is an interesting argument submitted by Ayabonga Cawe, a former economist for Oxfam. “Because of this white monopoly capital, most black Africans remain marginalised from the mainstream economy 22 years after apartheid,” he argues, and that “This seizure of Baba Danpullo’s assets undergirds the old argument that white monopoly capital is not new, but increasingly it’s used to deflect attention away from the real issues facing the country’s economy.”

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.