At least 10 journalists have been arrested in the past one year in what seems like a targeted clampdown on free speech with the use of the controversial Cybercrimes (Prohibition, Prevention etc) Act, 2015, Daily Trust reports.

Journalists from the International Centre of Investigative Reporting (ICIR), the Foundation for Investigative Journalism (FIJ), The Whistler Newspaper, and FirstNews Online, among others, have been arrested, detained and intimidated in the last few months.

Since its enactment in 2015, at least 25 journalists have faced prosecution under the Cybercrimes Act, according to a report by the Committee to Protect Journalists. The report, which was released in February, did not capture six other journalists that have been arrested and detained since then.

It would be recalled that President Tinubu signed amendments to the Act, including revisions to the section criminalising expression online, on February 28, but several reports indicated that there had been at least six journalists arrested and detained since the amendment was signed.

- NIGERIA DAILY:Why You Should Never Entertain Suicidal Thoughts

- I lost 5 family members in Gwoza attacks – Relative

Although the Act was amended earlier this year with a substantial adjustment on section 24, which listed what constitutes cyber-stalking and provided the punishment for such, the police and other security agencies have continued to rely on the previous definition of cyber-stalking to clampdown on journalists and other voices promoting open society and free speech.

What the amended Act says about cyber-stalking versus old provision

A review of the Cybercrimes (Prohibition, Prevention, etc) Act 2015, which the police have been using mostly for the arrest, detention, and in a few cases, prosecution of journalists in section 24, described the offence of cyber-stalking as “sending a message by means of a computer system or network that is grossly offensive, pornographic or of an indecent, obscene, or menacing character, or causes any such message or matter to be so sent or he knows to be false, for the purpose of causing annoyance, inconvenience, danger, obstruction, insult, injury, criminal intimidation, enmity, hatred, ill will or needless anxiety to another or causes such a message to be sent.”

But following criticisms, paragraphs A and B were replaced with new paragraphs that now described the offence of cyber-stalking as “sending a message by means of a computer system or network that is pornographic, or he knows to be false, for the purpose of causing a breakdown of law and order, posing a threat to life, or causing such a message to be sent.” The amendment, however, did not affect the punishment for the offence – three years of imprisonment.

This amendment, which many rights activists believed should have curtailed the indiscriminate arrest of journalists over every petition from persons who felt slighted by their publications, is yet to improve the working environment for journalists.

Contrary to this, the Minister of Information and National Orientation, Mohammed Idris, while speaking at an event to commemorate this year’s World Press Freedom Day, said no journalist had been incarcerated under the Bola Ahmed Tinubu administration for practising responsible journalism, stressing that the media is largely free in Nigeria.

But according to Reporters Without Borders (RSF), Nigeria is one of West Africa’s “most dangerous and difficult countries for journalists, who are regularly monitored, attacked and arbitrarily arrested.” The RSF’s 2024 World Press Freedom Index ranked Nigeria 112th out of 180 countries, worse than Niger Republic and Burkina Faso, which are both under military regimes. Last year, it held the 123rd position.

This report, when juxtaposed with the minister’s assertion, has made pundits to question the idea of “responsible journalism” as used by the minister to defend the government. They said that in this context, responsible journalism would be difficult to interpret and noted that recent happenings point to the fact that some people vested with power under the Tinubu administration were abusing it.

Arrests, detention and harassment

In February, Kasarachi Aniagolu, a journalist at The Whistler Newspaper, Abuja, was arrested while covering a raid on bureau de change operators in the Wuse Zone 4 area of the country’s capital. She was later released after approximately eight hours of illegal detention at the Anti-Violence Crime Unit of the Nigerian Police Force in Guzape, Abuja, her employer said.

Still in February, the police arrested Salihu Ayatullahi and Adisa-jaji Azeez, the managing director and editor-in-chief of Informant247 News based in Kwara State. They were arrested for alleged criminal conspiracy, cyber-stalking and injurious falsehood.

For recording a video of a labour protest over economic hardship in Warri, Delta State, officers of the Nigerian Army, 3 Battalion, on February 23, brutalised Dele Fasan, the bureau chief of Galaxy Television. Despite showing the soldiers his identity card, he was assaulted, hit with a gun, forced to delete images on his phone and handcuffed for an hour.

In March (which was after the president signed the amended Act), the editor of FirstNews Online, Segun Olatunji, was arrested and only regained his freedom after spending 12 days in custody. Gunmen in military uniform had allegedly invaded Olatunji’s residence at Iyana Odo, Abule Egba area of Lagos State on March 15, 2024 and whisked him away.

While the journalist’s family did not receive any communication from the military, the management of the media platform linked the incident to a story published by FirstNews, over which Femi Gbajabiamila, the Chief of Staff to the President claimed was defamatory against him.

In May, the executive director of the ICIR, Dayo Aiyetan, and a reporter, Nurudeen Akewushola, along with their lawyers, were detained by the Nigeria Police Force’s (NPF) National Cybercrime Centre. In the letter of invitation sent to them, the police stated that they were “investigating a case of cyber-stalking and defamation of character,” a popular accusation the authorities have used to clamp down on journalists and activists.

Days before the detention of the ICIR team, Daniel Ojukwu, a journalist in the Foundation for Investigative Journalism (FIJ), was arrested by the National Cybercrime Centre. His family and FIJ management were initially not aware of his whereabouts until 48 hours after he was declared missing, as he was not allowed to communicate with his family members and friends.

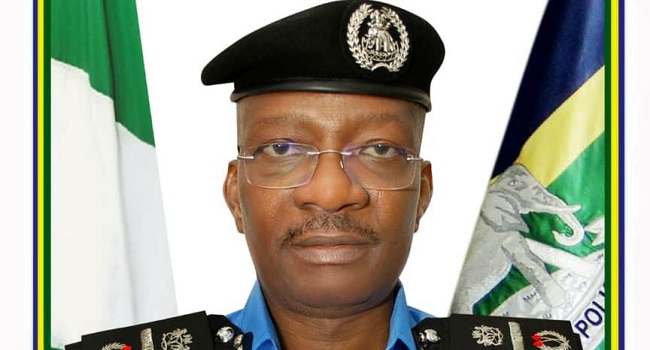

The police spokesman, Muyiwa Adejobi, later confirmed the arrest, saying it was based on a petition filed against him. “It is a case of violation of the Cybercrimes Prohibition Act 2015 and other extant laws of the land. He has a case to answer,” he said.

In the same May, Precious Eze, another journalist and publisher of News Platform, based in Lagos, was arrested based on a complaint from a prominent businessman and politician. Following his arrest, Eze was in detention for nearly one week before his colleagues from the Society of Digital Newspaper Owners of Nigeria (SDNON) learnt of his arrest and attempted to secure his release on bail, but to no avail. He was subsequently arraigned before two magistrates’ courts.

In another gestapo-like raid on journalists, police operatives on May 22 arrested Madu Onuorah, the publisher and editor-in-chief of Globalupfront from his residence in Abuja. The officers, who arrested Onuorah around 6pm in the presence of his wife and children, whisked him away in a private vehicle after seizing his phones and denying him access to his lawyer and relatives.

Daniel Ndukwe, the Enugu police spokesperson, noted in a statement that the journalist was arrested “after efforts made to formally invite him failed.” He said the security agency acted on a petition written to the Enugu police commissioner “over an alleged defamatory publication he made against a US-based reverend sister.”

After gaining his freedom, Onuorah narrated how he was arrested. He said the police tricked his 10-year-old daughter into opening the gate of his home and then “came in with guns, threatening me.”

Early in June, authorities of the Nigerian Police Force invited a journalist from Premium Times for a yet-to-be-published report. The reporter, Emmanuel Agbo, was invited over a land dispute story he was working on, Daily Trust learnt.

Agbo was said to have received the invitation letter dated May 31 from the Office of the Deputy Inspector-General of Police Intelligence Response Team (NPF-IRT) via WhatsApp. On May 30, the reporter was first contacted over the phone by a man who identified himself as a police officer named Ezemba Ezekiel. The officer asked the journalist to come over to the office of the IRT in Guzape, Abuja, to “clarify a petition.”

In October last year, Saint Mienpamo Onitsha, the owner of Naija Live TV, Bayelsa, was also arrested for alleged cyber-stalking. Reports stated that the journalist was treated as if he was violent and dangerous as officers drew their guns at him while effecting his arrest at the home of a friend, drove him to the local police station and flew him to Abuja. A week after his arrest, he was charged under the Cybercrimes Act for reporting tensios in the oil-rich Niger Delta region.

Marcus Fatunmole, an investigative journalist and news editor at the ICIR was harassed by security agents at the Eagle Square car park in Abuja while investigating the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) mass transportation scheme. He was not only assaulted, his phone was seized and the police violated his right to privacy by allegedly logging into his Google accounts.

These and many other unreported cases have formed the ordeals faced by Nigerian journalists in the course of their work, which are believed to have escalated in a period when the country is celebrating its 25 years of unbroken democratic governance.

Paradox to presidential proclamation, promises

The president, in his Democracy Day speech, alluded to the role played by the media in Nigeria’s struggle for democracy, saying, “We couldn’t have won the battle against dictatorship without the irrepressible Nigerian journalists who mounted the barricades along with pro-democracy activists.” He said this while flaying military regimes for proscribing media establishments and jailing journalists “for standing for free speech and civil liberties and the sanctity of the June 12 elections.”

Similarly, during a meeting with members of the Newspaper Proprietors Association of Nigeria (NPAN) in December last year, President Tinubu had assured of his administration’s readiness to uphold press freedom.

“You have held our feet to the fire, and we will continue to respect your opinions, whether we agree or not. One thing I must say is that I read every paper, various opinions and columns,” the president had said.

But despite these promises, media practitioners lament that instead of improved working conditions, they have continued to face harassment, threats and even illegal detention in the course of their work despite a ‘democrat’ being in the saddle of power.

Speaking with Daily Trust, Akintunde Babatunde, the programme director at the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID), Africa, emphasised that there’s need for stakeholders to call on the government to always follow the rule of law under any circumstance.

“In recent times, we have seen arbitrary arrest of journalists who published public-interest stories, with the explanation by the police that they were acting within the realms of the provisions of the Cybercrimes Act.

“The challenge we have here is more about the nature of the arrests and the approach of the police when it comes to journalists who are doing their jobs. We have seen journalists arrested without access to their families, lawyers or friends. We have seen journalists summoned just because they published stories that appear offensive to the authorities.

“The broader outlook of the Cybercrimes Act just makes it a potential tool against freedom of expression and against the fundamental role that journalists should play in democracy.

“I think it is important for us to call on every stakeholder to call on the government to ensure that the rule of law is followed under any circumstance. When people do their jobs and there are concerns, the police should go through the right channel with the right legal provisions instead of arbitrariness. These are issues we need to address in the country,” he said.

Media Rights Agenda (MRA) has also condemned recent acts of harassment and intimidation of journalists and media organisations by the Nigeria Police Force’s National Cybercrime Centre (NPF-NCC) over their reporting, and called on President Tinubu to take urgent measures to safeguard media freedom and terminate the abuse of the police and the Cybercrimes Act by powerful political figures and rich individuals to hound journalists performing their constitutional duties.

Media practitioners believe the trend has become more worrisome in Nigeria when a similar legislation is being adopted in other climes not known for press freedom to hound journalists.

In Jordan, Heba Abu Taha was sentenced to one year in prison for violating the country’s repressive 2023 cybercrime law on June 11.

According to the International Press Institute, which condemned the sentencing, Abu Taha was sentenced for “inciting discord and strife among members of the society.” She is the first journalist to have been convicted under Jordan’s new cybercrime law, marking an escalation in Jordan’s warfare against the press.

Police, FG, presidency mum

Several efforts to get fresh reactions from the police, the presidency and the minister of information and national orientation with the updated facts were unsuccessful. Several messages and calls to the police spokesman, Muyiwa Adejobi, from Tuesday were unreturned as at Sunday when this report was being concluded.

However, it could be recalled that the police spokesman had earlier noted in a statement that journalists did not enjoy immunity, noting that professionals were “criminally liable” once accused of a crime. He stated this while denying the allegation that the police were out for a witch hunt against journalists in a bid to suppress press freedom through the application of the amended Cybercrimes Act, 2024.

Speaking at a joint briefing by the security, defence and response agencies, organised by the Strategic Communications Interagency Policy Committee in Abuja earlier in June, Adejobi said the police were not preventing journalists from performing their duties.

“It is not that we are applying the Cybercrimes Act for witch-hunting; it is not to oppress or subvert press freedom in Nigeria. I am not saying you should not be a whistleblower, but if you want to be one, you must get your facts right,” he said.

The police spokesman said the police operated under numerous laws, and thus, did not necessarily need to use the Cybercrimes Act to prosecute journalists found guilty of publishing defamatory reports.

“Defamation of character is a law defined under the Cybercrimes Act; and the Criminal Act of this country defines defamation as an offence. If somebody publishes something wrong against you, as a Nigerian, you have the right to take it up,” he said.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.