By Tafi Mhaka

On June 21, Malawi’s President Lazarus Chakwera fired the country’s chief of police, suspended several senior government officials and also took the extraordinary step of stripping his deputy, Saulos Chilima, of all powers after they were accused of receiving kickbacks from UK-based businessman Zuneth Sattar in exchange for government contracts worth more than $150 million.

While Chilima is the highest-ranking official in Malawi to be removed from power over alleged corruption to date, few were shocked by the accusations. After all, it was only in January that Chakwera had to dissolve the country’s cabinet after three prominent ministers faced corruption charges.

- NIGERIA DAILY: Lecturers Call On God As ASUU Strike Bites Harder

- Why Nigerians should pay attention to humanitarian services – Rotarian Owonikoko

Sadly, a corruption pandemic is raging in Malawi – and on the rest of the continent.

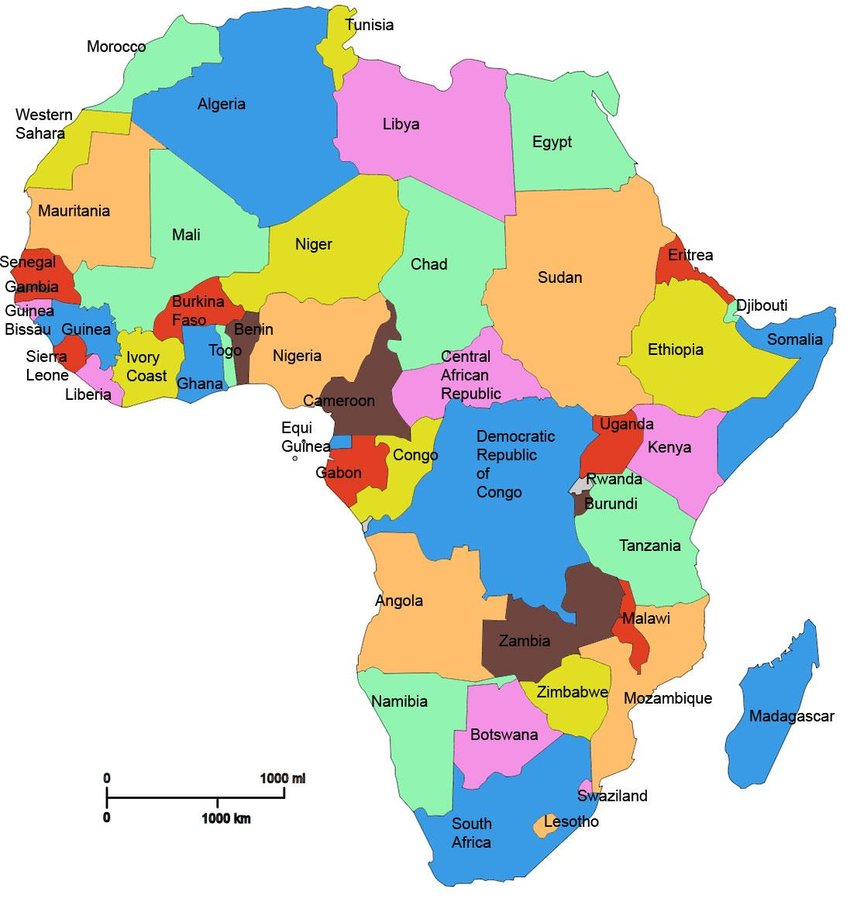

Indeed, from Malawi to South Africa and Zimbabwe, from Angola to Mozambique and Namibia, in countries across Africa high-ranking civil servants and their relatives, in cahoots with industry and business leaders, seem to have long been shamelessly stealing from the long-suffering masses.

South Africa, for instance, has recently been rocked by allegations that former President Jacob Zuma and a plethora of former ministers and CEOs of state-owned companies systematically planned and executed state capture to aid the wealthy Gupta family and line their pockets.

In Zimbabwe, Kudakwashe Tagwirei, a businessman allied to President Emmerson Mnangagwa, stands accused of amassing $90 million through a shady central bank deal.

In Mozambique, ex-President Armando Guebuza’s son, Ndambi, former Finance Minister Manuel Chang, and several other senior governing party members stand accused of participating in the disappearance of loans – taken out to finance maritime surveillance, fishing, and shipyard projects – worth $2.2 billion.

In Namibia, former Fisheries Minister Bernhardt Esau and former Justice Minister Sacky Shanghala stand accused of taking bribes worth millions of dollars from an Icelandic fishing company.

The damage high-level and systemic corruption inflicts on already struggling African economies cannot be ignored or written off as normal or negligible. The illicit activities of elected officials, bureaucrats and industry leaders are leaving states unable to deliver the most basic services to their citizens.

Just last year, acting UN Resident Coordinator Rudolf Schwenk said Malawi is unable to provide its citizens with “effective healthcare, quality education, accessible justice and an accountable and responsive democracy” because of high levels of corruption.

In addition to the localised corruption perpetrated through state-owned entities, the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) estimates that Africa loses about $88.6 billion, or 3.7 per cent of its gross domestic product (GDP), annually in illicit financial flows. This mammoth loss should not surprise anyone. After all, many countries topping Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, are all in Africa.

Small wonder then that Africa’s youth are extremely worried about the deplorable and depreciating state of affairs on the continent. According to the Africa Youth Survey 2022 published on June 14, Africa’s youths believe that the creation of “new, well-paying jobs” and “reducing government corruption” should be the continent’s two leading priorities.

Young people are clearly aware that corruption is perhaps Africa’s number one problem. But are the institutions tasked with moving the continent forward taking this devastating ailment as seriously as they should?

Well, they say that they do. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the African Union (AU) have each established protocols on corruption.

In reality, however, these institutions’ well-advertised efforts to fight corruption have hardly delivered any tangible gains.

The only thing that changed in recent years is the fact that, due to a public awakening about the harms of corruption, most African politicians are now feeling the need to announce their determination to fight corruption during their electoral campaigns.

These election promises, however, seldom transfer into action.

Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari, for example, ran for office on an anti-corruption ticket in 2015, but Nigerians believe corruption has, in fact, mushroomed under his watch.

Similarly, Ramaphosa staked his presidential campaign in 2019 on a pledge to set South Africa on a path of renewal, transparency and accountability, but South Africans believe corruption has actually worsened under his management.

Like Buhari and Ramaphosa, Mnangagwa’s anti-corruption campaign in Zimbabwe has yielded meagre returns and he stands accused of “presiding over a dysfunctional government, a corrupt government”.

So while Africa’s leaders are undoubtedly talking the talk, they seem unable to walk the walk.

But after a pandemic that intensified existing economic struggles, and amid a major conflict in Europe threatening Africa’s food security, among many other challenges, the AU cannot continue its fight against corruption with empty platitudes and box-ticking exercises.

The AU must establish credible continent-wide standards and independent surveillance mechanisms to advance the anti-corruption agenda, and implement them, vigorously, as a means to promote democratic principles and institutions, popular participation and good governance.

Eradicating corruption is not only essential to establishing firm adherence to the rule of law and political stability, but it is also critical to promoting economic growth and reducing poverty.

Source: Aljazeera

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.