Nigeria’s population, the highest in Africa and within the top ten in the world, is regarded as one of its strengths, especially its young population. But whether the large population becomes a blessing or curse to the country depends on what the government makes of it, analysts have said. Daily Trust Saturday reports.

Ranked the seventh most populous nation, Nigeria has a population currently put at about 211.11m by the National Bureau of Statistics, different from various other figures given by other agencies. The leading countries are China, India, the USA, Indonesia, Pakistan and Brazil, in that order.

There are worries, however, that a populous Nigeria could fail to become a prosperous nation. Economists who spoke to Daily Trust Saturday warn that while a high population is not necessarily a liability, the government must deploy policies to turn its citizens into an asset, a productive force. Nigeria’s failure so far in managing its burgeoning population explains the high incidence of poverty in the country, they noted.

Nigeria’s march into poverty has been evident. In 2018, Brookings Institution declared that Nigeria, with 87 million people in absolute poverty then, had become the World Capital of Poverty, having overtaken India, which had 73 million people. Earlier this year, Brookings raised the alarm that while in 2015 Nigeria had 80 million poor people or 11 per cent of global poverty, but that come 2030, Nigeria could account for as much as 18 per cent of world poverty or 107 million people.

- I have no regret starting as almajiri — Medical student

- Despite shrinking green spaces, horticulture business thrives in Kano

And in November, the National Bureau of Statistics shocked a bewildered nation with the announcement that as many as 133 million Nigerians, or 63 per cent of the population, were multidimensionally poor. It explained in plain language that Multidimensional Poverty Index measures poverty from the perspective of deprivations or exclusions that the poor suffer, and in this case in four broad areas. These were health, education, living standards, and work and shocks.

This measure is a more serious indicator than the previous measures that indicated the number of people living under the poverty line, says Prof Bongo Adi, an economist at the Lagos Business School. The information means that not only are these people living below the poverty line, they also do not have the necessary basic human capital that could help them to escape from poverty, he explains.

“Such people lack education; they lack access to healthcare. So, you have a population that will go extinct, unfortunately,” he says. It’s so unfortunate that we could use such word for human beings, but that is what it means. Such people cannot afford the necessary enablement that can grant them access to opportunities to grant them the skills and competence to save themselves from their situation. They don’t have that,” says Adi.

Also, they don’t have the human stability that health gives us. Health enables us to work, to live without any sort of lethargy. Now, they have a certain level of morbidity imposed on them by poor health conditions.

According to figures from the World Bank, Nigeria’s population growth rate was highest in 1978, when it was 3 per cent. Since then, the growth rate has fluctuated. In the period from 2009 to 2013, it was stable at 2.7 percent, but declined to 2.5 per cent last year.

This high population growth rate and the high fertility rate predispose Nigeria to population explosion. Already, there are projection that by year 2050, Nigeria’s population will rise to 400 million, displacing the United States as the third-largest country.

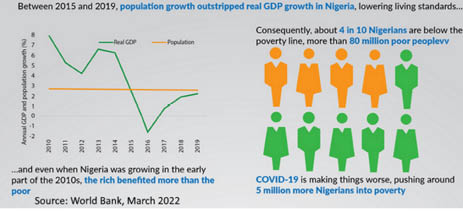

Unfortunately, the country’s GDP growth rate is currently put at 2.5, which explains a recent comment by the IMF, that the Nigerian economy “is expanding at slightly above the population growth rate.”

This steep slide into poverty was not there in the period prior to 2014, says Dr Ayo Teriba, an economist. He recalls that the period 2004 to 2014, could be described as the golden age of Nigeria in recent times, when the Nigerian economy grew from being number 52 in the world in 2000, and by 2012, it was the 22nd largest. The economy, skipped 30 places, with implications for the well-being of Nigerians.

“So, it did not matter that we had a large population; we were the 7th largest in terms of population, but we were growing faster than many other countries. We were recording 6 to 7 per cent growth in GDP,” Teriba, the CEO of Economic Associates, a consultancy, told Daily Trust Saturday. With that, Nigerians’ welfare was improving. It was within that period that the telecom sector grew; it was the time the Nollywood sector grew, and the ICT sector grew, as the rebasing of Nigeria’s GDP in 2014 revealed.

“We were the envy of other countries. Nigeria was widely expected to join the ranks of the top 20 economies in the world by 2020 and then came the collapse of the oil price,” he lamented.

One of the positives about Nigeria is its youthful population. Worldometer, a population platform, puts Nigeria’s median or middle age at 18 years, versus 38, 28 and 38, for China, India and the USA, respectively. It also puts Nigeria’s fertility rate at 5.4, while the three leading countries have 1.7, 2.2, and 1.8, in that order.

Classifications of Nigeria’s population by the World Bank put the age bracket of zero to 15 years as accounting for 43 per cent of the entire population, while the 15-64 group accounts for a whopping 54 per cent. This leaves just three per cent for those 65 years and above.

Prof Adi says these demographics must be handled with care. “You know that when you have a large youthful population who are highly fertile, the population will not drop any time soon,” he observed. According to him, Nigerians sometimes tend to idolize the youthful population, seeing the bourgeoning youthful group as the critical human resource that will power the country and give the nation an advantage.

“But we fail to realise that if half of the population is young people, then there is the tendency that the population will be increasing in geometric progression. So, when you have that level of progression, eventually you will see that the Malthusian prediction will come true.”

Thomas Robert Malthus, the 18th-century British economist, had warned in his population theory that “By nature, human food increases in a slow arithmetical ratio; man himself increases in a quick geometrical ratio unless want and vice stop him.”

So, what is the likelihood that the standard of living in Nigeria will improve when we have not managed to invest in human capital, in building up the capabilities of the bourgeoning population? Adi asks. Even if the growth rate is at three percent or 2.5 percent, the average growth of the economy in the past seven years has not gone beyond two percent, he points out.

“That is a sitting time bomb,” Adi warns.

Teriba and Austin Nweze, another economist from Lagos Business School, believe a large population has more advantages than disadvantages. “There are advantages of populations, depending on how you manage them,” says Nweze.

If you make them productive like China, which has made its people productive. He also cites the examples of Brazil and Indonesia, which he says have made their middle class in charge of their economies. “There is no middle class in Nigeria,” he laments.

Teriba on his part notes that six other countries have larger populations than Nigeria, with the largest two of them – India and China – having the current best examples of economic growth and economic prosperity. “So, a large population does not have to be a liability. A large population can be an asset,” he asserts.

Continuing, he notes that “countries without large populations are now relying on immigrants from the countries without large populations. They are now giving visas and passports to migrants, like begging migrants to come into their countries. Nigeria is not in that position; Nigeria will never be in that position as long as we have a virile population. So, the population is an asset, not a liability; it’s a strength, not a liability.”

The solution to these challenges, the economists say, is to return the economy to the path of growth with jobs. Apparently, Nigeria’s growth had been fuelled from 2000 to 2015, for 15 years, by a favourable oil price, enabling the country to enjoy what Teriba calls “15 fat years. And then came the lean years since 2014.”

So, we have been well for longer than we have been in this lengthy situation of national poverty, and the sooner our government learnt to adjust to that collapse of oil prices, the sooner our government learnt to move beyond an oil-fuelled economy, the better we would be able to bring ourselves back on the growth path that is needed to lift our populace out of poverty and put our populace on the path to prosperity.

For Adi, the way out is for the government to target industrialization or the growth of the real sector. “Today, the problem of Nigeria is not just that the jobs do not exist, but that the conditions to create or start businesses are completely constricted that no business can run consistently as it is today,” he said.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.