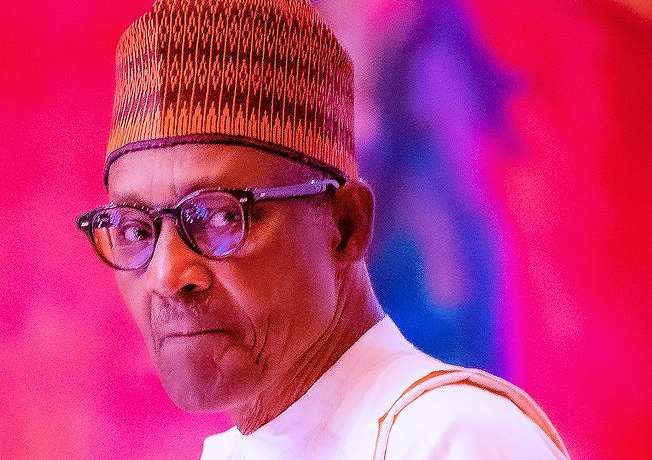

Left to me, we should no longer be talking about Muhammadu Buhari. But how can move on when he continues to remind us of the misfortune that he was?

So let us talk about Buhari, beginning with the article, “One Hundred Days After Buhari,” by his former spokesman, Garba Shehu.

It is important to push back on this article because not only does it attempt to reconfigure Nigerian history in Buhari’s favour, it brutalizes and insults his victims: the ordinary people of Nigeria who trusted him in 2015.

Mr. Shehu recounts “successes” of his former principal, some of them true, some false, most of them overstated, as a basis for clobbering and bludgeoning Buhari’s critics.

Every leader has a measure of “success,” some of which he may have had nothing to do with. That is the nature of governance as an enterprise.

The problem with painting Buhari in colours of glory is that they are colours he promised but never delivered. As I have written elsewhere, we cannot measure Buhari in the same way we measure Goodluck Jonathan or even Olusegun Obasanjo, predecessors of his whom he lampooned for a decade and a half as he sought the presidency.

Why? Because Buhari’s problem with them was framed in terms of character and ambition. He positioned himself as the anti-Obasanjo and anti-Jonathan ultra-patriot who would provide the strength of character to lead Nigeria for Nigerians.

Remember, Nigerians were tasting of Buhari for the second time. As Head of State, and then, 30 years later, as President.

That first time around—young and spritely, and complemented by the unsmiling Brigadier Tunde Idiagbon (whom those who do not know should look up)—holding himself up in a practiced pose and arriving in stiff fatigues—Buhari was the handsome picture of reassurance. Unfortunately, his excesses within just two years caused his military buddies to eject him from power.

Buhari took umbrage. For the next 30 years, he grumbled and bristled and plotted. He dismissed others as corrupt and advertised himself as Mr. Anti-Corruption. He said he was a patriot.

By floundering, Nigerian leaders handed him a priceless gift, making of him a fiction of credibility and political attractiveness.

In time, he became the face of the marketing of the APC. He was the anti-PDP, the previous symbol of Nigerian greed and dysfunction. Buhari vowed. He preached. He begged.

But he was simply power-hungry. And from his first month in office until his last, he provided evidence that both he and all who said he had integrity were fraudulent, or at best, deluded.

The reality is that Buhari had no idea what leadership was. He assumed he could play the part of a Nollywood actor jetting from one place to another to read written speeches handed to him by paid officials.

But leadership is conviction and character and responsibility. Literally within days of assuming office in 2015, time and chance provided him with an opportunity to reintroduce himself when Breaking Times, an Abuja-based newspaper, published an unusual article.

“President Muhammadu Buhari owns the sprawling Asokoro lakeside mansion located at number 9, Udo Udoma Street, Asokoro, Abuja,” it wrote, following which the newspaper’s website disappeared.

Time after time after time, I called on the presidency to refute the story, which, at the very least, meant that Buhari owned six homes, not the five he had reported.

Buhari persisted in his two-track dichotomy between what he said and what he did. In November 2016, for instance, the presidency swore that Buhari would “always tell Nigerians the truth.”

Really? In Shehu’s 100-Days review, he said, “In the eight years he led the country, Muhammadu Buhari had taken many decisions and as is human, one or two may have been wrong. But no one, not even critics, can question his intentions when those decisions were taken.”

The same Buhari who did not address the Breaking Times’ story?

Is it the same Buhari who ignored two federal courts—in February 2016 and July 2017—which had ordered his government to publish records of recovered stolen funds since 1999, including detailed information of what had been spent and what it was spent on; and a list of the high-ranking public officials from whom his government had made recoveries? That Buhari?

Is it the same Buhari who set up three “investigative” committees to pacify the international community in 2016 after the Global Fund cried out that its funds were being looted by Nigerian officials, only for him never to publish a single report or punish a single official? That Buhari?

Is it the same Buhari whose government, in 2016, received 200 tons of dates from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia as a Ramadan gift to Internally-Displaced Persons, which never reached them but were instead found being sold in open markets? That Buhari?

Is it the same Buhari who secretly “sold” thousands of assets that had been forfeited to the government but who never disclosed what was sold and what was given to friends and cronies? That Buhari?

Is it the same Buhari who ran the unprecedented specie of nepotism that Farooq Kperogi called “Buhari’s government of his family, by his family, and for his family”? That Buhari?

Is the Buhari to whom Shehu refers the same one who claims to have championed the cause of infrastructure in Nigeria, but which borrowed and squandered meaninglessly? The Buhari who returned from his state visit in 2016 with additional investments “exceeding $6 billion” that no Nigerian ever enjoyed?

Is it the same Buhari whose roads and rail were rarely completed? The one who has yet to account for the billions and billions he squandered in the rail sector? The one who did not think it was his business that the Abuja Light Rail he commissioned in 2018 was dead two years later in the city in which he ruled?

The one who said he was building roads all over the country, none of which he could identify or complete?

Shehu wrote that as a human being, Buhari “may have made one or two wrong decisions” during his tenure, but that there was no area that was not “touched by the Buhari government.”

Certainly, anyone can make a mistake. But this is not about “touching,” but about achievement and impact. The records show that Buhari was concerned only about Buhari, he did not know the meaning of empathy or compassion or service.

It is why he spent a significant amount in a foreign hospital, without building one in Nigeria. He could give the presidential jet to his children for school projects but not honour his pledge of a national airline

In the end, for anyone to write fresh propaganda for Buhari 100 days after his departure is confirmation of a failure so colossal it borders on betrayal.

“If Nigeria does not conquer corruption,” he used to advertise, “corruption will conquer Nigeria.”

In eight years, corruption conquered and exposed Buhari and his indolence, indifference, and duplicity. As a ruler, he was a weakling who brought Nigerians tremendous regret, and he will always be remembered with anger and sadness.

And I do not buy the line that he is at his farm four days a week. It is in London, far away from Nigerians and under the gaze of foreign nurses, that he is at home.

He is not an icon. Not a hero. Not an achiever. Not a champion. Not a statesman. He is not missed.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.

Join Daily Trust WhatsApp Community For Quick Access To News and Happenings Around You.